You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Tate Britain’s Painting Now exhibition – a collection of works by five selected artists – leads the spectator to reevaluate not just what art means in Britain today but, ultimately, the very nature of the world and society. The exhibition curates works by five chosen artists – Tomma Abts, Gillian Carnegie, Simon Ling, Lucy McKenzie and Catherine Story – as a gauge of the state of British painting. As it happens, it is also a gauge of British class-angst and discomfort: each artist contradicts her or his past and interrogates the history of painting itself.

German-born artist Tomma Abts is the first painter encountered in the exhibition. She works with acrylic paint and oil on canvas, until one reaches Jesz (1998) made of patinated bronze. It bears the illusion of mint green paint scraped to replicate verdigris. Alongside her psychedelic, illusionist paintings of straight neon and dark lines, it reminds us that we are aesthetically conditioned – particularly when things are not as they seem.

Simon Ling’s work features Untitled (2013), a fantastical, dreamlike painting of a bag shop in Hackney. There is a nostalgia about Ling’s work, even the artificiality of highlighter, Day-Glo colours that peep through his murky settings: a subconscious nod to graffiti art in any urban streetscape. Ling’s preoccupation with the minute detail of everyday life and focus on the CCTV camera exposes a commentary on urban discomfort and the surveillance state. Yet Ling manages to find depth and emotional connection, as shown in his still life composition of a council block and the “orgy of abundance” in his rundown high street shock paintings.

Story, meanwhile, projects abundance and intensity through her muted paintings Lovelock (I), which depict Golden Age film cameras. Story’s paintings do not work in isolation: viewers become bored, agitated and want to move onto the next thing. This is where Story’s inclusion in the exhibition is remarkably significant. It raises commentary on our need for instant gratification – for everything to be in glorious Technicolor. In this room, we become actors, pretending to like what we see in the subdued terracotta palette on wood. As a contemporary artgoer it shows that we have become trained to always scrutinise what they see.

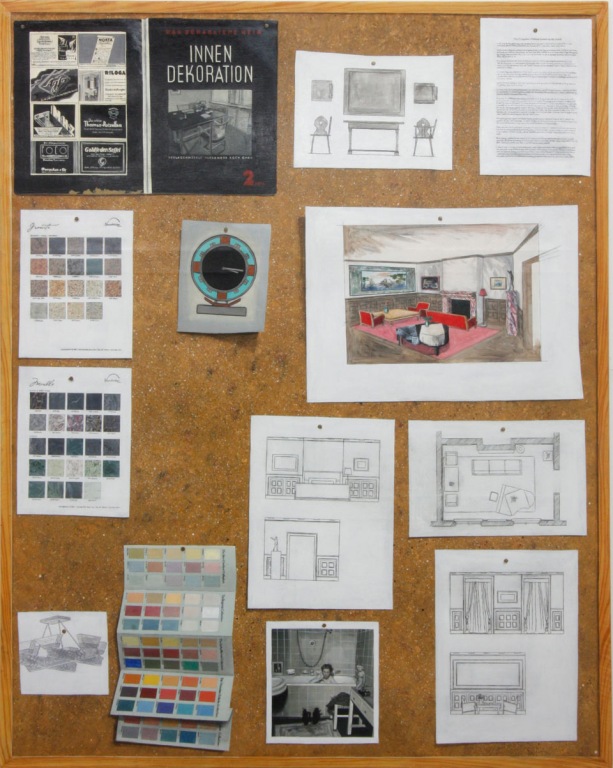

The standout artist of Painting Now, however, is Lucy McKenzie. It is clear that exhibition curators Lizzie Carey-Thomas, Clarrie Wallis and Andrew Wilson took the most care with McKenzie’s conceptually sound work. However, to the uninformed viewer, her group of trompe l’oeil still life paintings – titled Quodlibet XX Fascism, Quodlibet XXI Objectivism and Quodlibet XXII Nazism (2012) – lose their titillating aspect in an anxiety-ridden British society. It is only when you look closer at her distinctive style – interior design and craft techniques alongside the iconography of autocratic regimes – that we realise that McKenzie is remarking on the loss of the intellectualism in painting. Painting, to us, is now the colour Dulux charts at our local DIY superstore. The two most significant pieces in the exhibition are Quodlibet XXVI (Self Portrait) and The Girl Who Followed Marple (2012): both comment on the construction of the self through social media and false means. Here, McKenzie comments on the manipulation of the exterior to project a highly literal image – something which, historically, was associated with the medium of paint. The Girl Who… is a must-see to clarify this point.

Painting Now is a wonderful cacophony of top British painters, working with an array of materials, colours and conceptions. In our academically advanced age, Painting Now is not just an exhibition to be seen: it is an exhibition to be read. Each of its rooms marks a new page in British art history. Tellingly, the tone is often downbeat: there is a sinister motif running through all their works, whether it be literary dystopia – we like our dystopias at Litro – or the underlying dread and angst in current British society. This impressive and subtly radical exhibition will appeal to new and old art lovers alike.

Painting Now: Five Contemporary Artists continues at Tate Britain until February 9 2014. See the Tate website for more information.

About Nikki Hall

I am a London-based writer, bookseller and literary critic. I also edit the Philosophy section of Inky Needles, a literary and cultural theory publication. (www.inkyneedles.com) I have an encyclopaedic knowledge of American literature and have a penchant for the macabre, the transgressive and the different. I have written for the Independent, BBC, Film/Philosophy journal, Review 31 and worked for Literary Review and The Week. I am currently (well, trying to) writing a book on American Dreamers to Psychos: A Critique of American Literary Tradition (Zero Books) and my first novel, Seven Sisters.