You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The spirit of acquisition is strong in the world. People hoard bottle tops. They collect magazines. They stack old vinyls in their garages. And a long, long way away on the other side of the financial spectrum, they part with millions for works of art.

From where in us does this urge spring? Kenneth Clark, one of the great cultural critics of the 20th century, simplified collectors into one of two camps: those who are enchanted by beautiful objects, and those who wish to put them in a series. The urge to adore things, and the urge to possess and control them. I think they tend to go hand in hand. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Clark compared collecting to falling in love. Certainly they both bring out the madness in people.

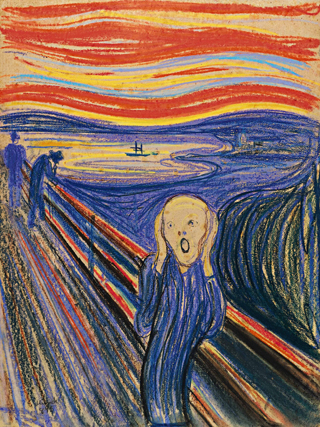

Nowhere is this madness writ louder than in the globe’s great auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s in London and New York, where art market records are shattered year on year. Half in horror, half in awe, I track these colossal sales.  Screamby Edvard Munch. Munch’s The Scream went in May 2012 for $120 million to a leveraged buyout specialist from America named Leon Black.

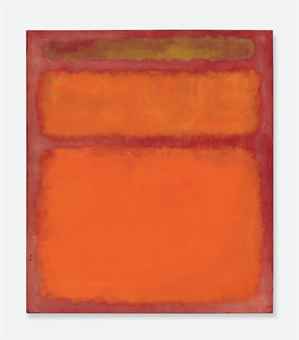

Screamby Edvard Munch. Munch’s The Scream went in May 2012 for $120 million to a leveraged buyout specialist from America named Leon Black.  Orange, Red and Yellowby Mark Rothko. Less than a week later Rothko’s Orange, Red and Yellow was bought by a private collector for $86mn. And the year before this the Royal Family of Qatar drained the desert of its oil to spend $250mn on Cezanne’s The Card Players, making it by some distance the most expensive painting ever bought.

Orange, Red and Yellowby Mark Rothko. Less than a week later Rothko’s Orange, Red and Yellow was bought by a private collector for $86mn. And the year before this the Royal Family of Qatar drained the desert of its oil to spend $250mn on Cezanne’s The Card Players, making it by some distance the most expensive painting ever bought.

This heady record stood for almost four years (a lifetime in the world of contemporary art) until it was broken in February this year when Gauguin’s oil painting When Will You Marry Me? was sold by Swiss collector Rudolf Staechelin for $300mn. The buyer is not formally known, but it is rumoured to be another high-powered raid out of the State of Qatar. And all this for a painting that couldn’t even find a buyer to cough up 1,500 francs when it first went on sale a little over 120 years ago in Paris.

But, somewhat paradoxically, splashing obscene amounts of cash on works of art that somebody else has designated great seems to me a slightly cheap way of fashioning a collection. And in any case, it is certainly a method vastly beyond the means of more or less all of the world’s population, and so not one worth paying much attention to.

I prefer the collectors who are long on judgment and short on money. Real collecting is always the front-runner of the art market, and true taste moves faster than fashion. Take the New York couple Dorothy and Herb Vogel, who amassed one of the world’s great collections of Minimal and Conceptual art on a post-office clerk’s salary. Or people like André Breton and George Costakis who scampered around the world buying pieces on a shoestring. Or the great art historians Roger Fry and Kenneth Clark who bought ahead of the curve, always anticipating – and to some extent creating – the art manias of the next decade. Even Andrew Lloyd Webber, displaying a taste occasionally absent from his musicals, bought shunned Victorian masterworks for £50 on the Fulham Road.

Clearly, collecting beautiful things is not the prerogative of the insanely wealthy. They come later, after good taste has had its say and all things have been ranked. Then enter the House of Thani, the Roman Abramovichs, the slow-footed, buying what they have been told to buy.

But in 21st-century London, what is our equivalent of the Paris flea market, where masterpieces are stacked against dross, waiting for a discerning eye to rescue them? To answer this, I started on the yearly round of spring and summer shows that highlight the best work of London’s up-and-coming artists. My journey began at The Other Art Fair on its opening night on the 23rd of April, giddy on that intoxicating triumvirate of pursuit, possession and aesthetics.

Certainly, the Fair marketed itself as a place where one might discover ‘the next big thing’. Its guide proudly quoted Timeout magazine’s claim that this was an opportunity to ‘Discover art stars of tomorrow’, while the Fair’s Director wrote: ‘You can purchase with confidence knowing that you are investing in artists who are serious about their careers.’ If this seems a little mercenary, not quite enough ‘art for art’s sake’, then it is perhaps worth reflecting that although the buyer has always proved a slightly awkward dance partner for the creator, there is no relationship more symbiotic. Neither can exist without the other, and so the collector – perhaps animated by greed, perhaps by the vanity, perhaps by pure good taste – is as valuable a part of the game as the artist in his studio.

I was far from the only person who felt the urge to acquire that evening. The event was held in Victoria House on Southampton Row, built for and formerly inhabited by insurance firm The Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society, and now a somewhat odd blend of office, retail and leisure space. The building is impressive without being attractive. Inside it was thronging with people, clutching plastic champagne flutes and peering hard at paintings, trying to decide whether perhaps this could be the work of one of the promised ‘art stars of tomorrow’. I was doing exactly the same thing.

Part of the pleasure of attending a show exhibiting emerging artists is the scope it offers to exercise real personal judgment. This is down to the disparity in the quality of work displayed. Walking through the National Gallery past an endless procession of Rembrandts, Goyas and Van Goghs can almost become a numbing experience. There are no peaks and troughs, only brilliance. At the Other Art Fair the work ranged from the very good to the poor, and my senses were all the more engaged for it.

I was also drawn by the allure of the unknown, the possibility that within these rooms was a gem, and no one could guide me there but myself. And, of course, I was spurred on by the thought that someone else might find it first. So I walked rapidly through the exhibition, scouring the walls hungrily. There were 130 artists represented at the Fair, but many could be dismissed at a walking pace, allowing me to get round the show in an hour. When I saw something I liked I bent quickly and scooped up the artist’s business card, darting off before they could nervously engage me in any uncomfortable sales patter.

With all the work at least scanned, next came the gestation period, a pause in a quiet spot to allow my senses – overwhelmed by the volume and range of what I’d just seen – to settle once more. This is often a time of disappointment. The first lap around an exhibition can often seem underwhelming. I don’t have an explanation; perhaps art has no equivalent to love at first sight. It needs a little time to burrow its way in.

After this rest I set out again, back into the bustle of the exhibition. The second time round is different. I feel myself drawn to certain artists without entirely knowing why. New qualities emerge. Some works reassert themselves while others fade almost to the point of becoming invisible. On the second lap, you realise what has left an imprint, subliminal and subtle.

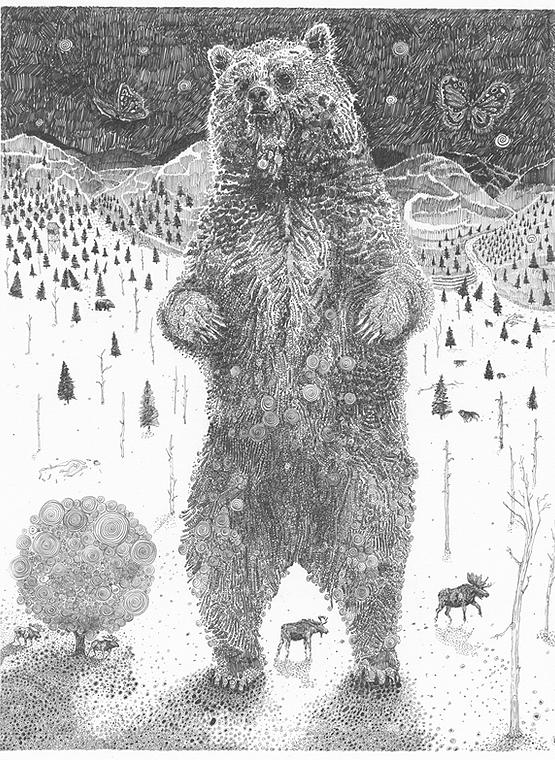

Some things it is almost embarrassing to have missed.  bearby Oliver Leger. Olivier Leger’s ink drawings of animals, for instance, erupt with detail: an enormous whale is pursued by pods of little orcas, manatees frolicking around its cheeks and watery trees sprouting from its back, an ecosystem on a journey, full of the fecundity of life; a bear, straight out of some perpetual fairy tale, standing erect, on the cusp of speech, suggesting the possession of a deep secret, wolves padding lightly around its ankles.

bearby Oliver Leger. Olivier Leger’s ink drawings of animals, for instance, erupt with detail: an enormous whale is pursued by pods of little orcas, manatees frolicking around its cheeks and watery trees sprouting from its back, an ecosystem on a journey, full of the fecundity of life; a bear, straight out of some perpetual fairy tale, standing erect, on the cusp of speech, suggesting the possession of a deep secret, wolves padding lightly around its ankles.

On another wall are Lauren Jetty’s cross-stitched versions of iconic portraits which, according to the artist, suggest ‘the boundary between computer and human, heart and hard drive’, but to me just seemed very beautiful and very delicate, a fraction of a face captured for a moment in the darkness.

Are these the art stars of tomorrow? Only time will tell. There is so much more to that than talent. But it doesn’t really matter. The art is lovely. And it is affordable, in the loose sense of the word. Short of theft, a collection is always going to be difficult to acquire on a minimum wage, but the bulk of the work at the Fair was selling for anywhere between £200 and £1000.

So if you are feeling the urge to acquisition, then now is the time to strike. The Other Art Fair may have passed for this year, but a host of other events are upon us. Away from the dusty halls and austere visage of the National Gallery, new art is being minted everywhere this summer in London. Visit the ‘Free Range’ exhibition (26th June to 13th July) in the Truman Brewery on Brick Lane, where over 3,000 students exhibit art, architecture, fashion, design, photography and interior design, or go to the Royal Academy Schools Show, where their graduating class of seventeen shows the fruit of degrees (open until the 28th June). On the other side of London The Royal College of Art in Battersea is also showing its postgraduate exhibition in Painting, Photography, Printmaking, Sculpture, Ceramics and more between the 25th June and the 5th July.

So go and hunt in the hinterland between an artist’s education and the burgeoning of their career. And if you buy what you love to look at, then you are making an investment that will never depreciate in value, whichever way the stars align.

About Harry Waight

Harry Waight is in his twenties, and spent his youth travelling around the world in pursuit of his parents. He returned to England to study history at university. He currently lives in London, plotting to escape again. In the meantime, he enjoys writing about things he has read, watched or heard.