You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In the book world, very little can compete, for sheer excitement, with the end-of-year best-books retrospective lists. The entire month of December, give or take half a week at the beginning, is essentially devoted to this subgenre. You can hardly open your web browser before Christmas without coming across an esteemed critic (or several) listing their five or ten or fifty picks of the past twelve months’ releases. As a signal that the festive season and year’s end are upon us, it’s akin to all the lights going up on Oxford Street and the Salvation Army rolling out their brass bands.

The one thing that can and does compare is the frenzy over the beginning-of-year most-anticipated-books lists. This is, in its own way, a significantly weirder phenomenon because much of the selection process has the appearance of being a stab in the dark. In a best-of-year list, after all, you can ask people who have actually read the books, because the books have already been released. In a most-anticipated list, even well-connected publicity folk with access to six months’ worth of pre-publication copies probably won’t have read all of them.

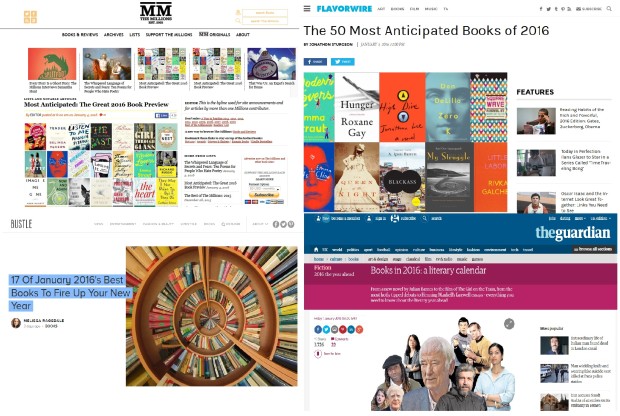

And yet sites keep churning these things out. The Millions has made its New Year’s list a major feature; devotees celebrate its annual return. Bloggers, in particular, are good on lists, and often use them to generate buzz around a title or genre they’re especially keen on. People want to read them. I’m no exception. I spent a good forty-five minutes this morning zipping through The Millions, The Guardian, Flavorwire and Bustle, my mouth slightly agape, pausing occasionally to make note of a title that looked particularly good. They say books are an addiction; if that’s the case, lists like these provide an almost orgiastic sense of satisfaction, an itch scratched, a fix.

There are a few reasons for this, some more elevated than others. For one thing, there is the professional aspect of it all. Those of us who either make our livings in the book industry or are hopelessly enslaved to it through personal passion (or indeed both) can’t afford to not know about, or to promote, new titles as early as possible. The power of these lists comes from the advantage that they can provide to a proactive publicity department. I follow several dozen literary publicists on Twitter, and every one of them has, at some point in the last few days, tweeted some joyful variant on “One of my titles is on a books-to-look-out-for list [insert picture or link here]. Day made! [emoji]” They’re not wrong to be jubilant—it’s their job to get this work as widely noticed as possible. I suspect, however, that this imperative is a very large part of what drives editors to commission beginning-of-year lists: they can give a serious commercial boost to an industry that has learned, over the last decade and a half, to panic constantly about its chances of survival.

Less cynically, of course, lists are psychologically satisfying. For semi-professional readers, they are surveys of the territory ahead. Book blogs are booming, and you can’t write a serious book blog without a schedule. In order to request copies in time, you need to know what’s coming. These round-ups provide a way of doing so that doesn’t involve trawling through endless catalogues (although it’s likely that many bloggers will do that anyway.) For the casual reader, though, the celebrated man or woman in the street who likes to curl up in their armchair with a novel of a night, these lists primarily promise quality control. In this sense, they’re exactly like end-of-year bests, only without the underlying sense of smugness if you recognize a handful of titles that you’ve already read: they allow you to signpost titles and covers in your mind, so that when you see them in the shops several months later, you know you’re not taking quite such a big chance.

Or at least that’s the idea. In reality, of course, you’re taking a huge chance, but the list format makes it appear as though the real gambler is the books editor or columnist who has deemed the book worthy of anticipation. Lists like this trade on the presumption of trustworthiness. Believe us, is the subtext. This is what we do all day. We can sort the wheat from the chaff. Most readers, I think, know on some level that this promise is hollow. It’s only common sense: no one is going to like all of the books recommended to them. But the fiction of impartial judgment is so useful that we allow it to endure. We rather have to, otherwise we’d have to do every bit of the weeding-out ourselves.

And, quite frankly, long may it continue. The first news story I saw when I woke up this morning was about the child that the British press has dubbed (with questionable taste) “Jihadi Junior”; the next was about parental inability to monitor their offspring’s electronics usage; the third was about North Korea’s hydrogen-bomb test. We live—not unusually; humans have always lived thus—in an age of uncertainty and violence and, at times, despair. The books we anticipate at the beginning of the year, and the books we laud at the end of it, sometimes, in the in-between months, manage to unfold our state of being to us: our fear, our hypocrisy, our humour and our joy. Why shouldn’t we make lists of them?

About Eleanor Franzen

Eleanor Franzén is a London-based writer and editorial assistant. She blogs about books at Elle Thinks (https://www.ellethinks.wordpress.com).

One comment