You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

My doctor’s office quietly shut its doors, sending out letters to all patients that it had been absorbed by a local mega-healthcare company with a not so hot reputation. They had recently rebranded themselves with the fancy, sanctimonious sounding French name, “Bonne Santé”, and proceeded to improve their brand by buying up all the reputable local doctors and putting them under their single roof. They built a new building to house these doctors, shaped it in that typical neo-geometrical, baffling modern style with mostly glass walls, resembling a square building block with a sphere sitting on top of it and a triangle laying on its side for a roof. I could no longer reach my doctor directly, and instead had to go through a switchboard of numerous individuals dwelling somewhere in that glass maze to even make an appointment.

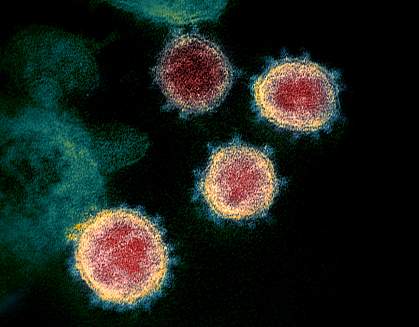

So when Covid-19 hit, I started having symptoms. It was like the worse cold I’ve ever had, with bouts of breathlessness once or twice a day. I secretly hoped to just die so that I didn’t have to deal with this merged, corporatized health care company that I knew was always a confusing mess to accomplish anything with. It was a brave thought, but like most brave thoughts it was quickly abandoned when I actually faced the real fear of dying when the breathing trouble increased. So I sighed and called the healthcare conglomerate.

There was only one other person in my county who had Covid-19 at the time, he was prominently featured in the local paper. He was an older man, a total shut-in who rarely left his house, who had no idea how he caught it. That, oddly, sounded just like me.

I called my doctor’s mega-office, only to be told by a nervous, distracted, and somewhat insecure sounding receptionist that no doctors in the company were seeing any patients who had any cold or flu like symptoms due to fear of spreading the infection. She said that in a few days a special flu and cold center would be opening to handle all these cases. She suggested I call them. I asked if there was anything more she could possibly do, and she basically gave me a wavering answer that amounted to, “Well, I don’t know.”

“But … there’s only one person in the county who has it,” she tried to assure me, “and you said you don’t go out a lot, and haven’t come into contact with anyone who had it, right?” she asked, trying to sound optimistic.

“Yeah but … the guy who got it didn’t go out a lot, or have contact with anyone who had it either,” I countered.

“Yeah, so, you should be fine!” she said quickly, and then ended the call, either oblivious to or purposefully ignoring my point.

I sighed as I hung up the phone and began immediately dialing the cold and flu clinic. After waiting on hold for an hour, I got through to someone who told me to contact my local doctor if I needed treatment.

I explained I can’t contact my local doctor, for one, but my local doctor’s mega-conglomerate corporation that lords over him had told me to call their number.

She simply repeated that I needed to contact my local doctor. I hung up the phone.

I dropped the matter for several days, once again reasserting my desire to just die rather than have to deal with any more corporate healthcare bureaucratic runaround. That idea was dashed once again, when I woke up one morning, completely out of breath, and feeling like I was going to faint.

I immediately called the doctor’s conglomerate. They told me to call the cold and flu clinic again, even though I explained I already had, but it was no use.

I called the cold and flu clinic again, and was on hold for an hour and a half. Somehow, probably totally unintentionally by the health care company, I think my breathing got easier as I listened to Crocodile Rock on a loop, for dozens of times, playing from the recorded on-hold system.

“Hello, the is the cold and flu clinic hotline,” somebody finally greeted me, “I have no information on Covid-19 or any Covid-19 testing, how may I help you?”

“Um,” I said, “Well, I’m pretty sure I have Covid-19.”

“I have no information on Convid-19 or Covid-19 testing,” she repeated robotically, sounding very bored and irritated by having to repeat herself.

“Well … I just want to know what I should do…” I said, unsure how to phrase what I meant. If the fever, lack of sleep, and breathlessness wasn’t enough to affect my coherence, then the heavy dose of narcotic cough syrup I’d been taking had amply made me a stammering, awkward mess.

She repeated again, “I have no information on Covid-19 or—”

“Ok! Ok!” I cut her off. Then sighed. Then hung up the phone.

I looked around on the health care company’s bloated, colorful website, and eventually found a number for a Covid-19 hotline, advertising that it should be called, “For Covid-19 concerns, information, and if you think you’ve been infected.”

Strangely, the on-hold system to this number sounded exactly the same as the one for the cold and flu clinic, playing Crocodile Rock over and over again, this time I think my breathing got worse as I listened, and my head spun as I was growing slowly furious.

I was on hold for an hour, when I was greeting by the exact same voice, “Hello, this is the Covid-19 hotline, I have no information on Covid-19 or Covid-19 testing, how may I help you?”

I was silent for quite a while, as I don’t think I ever heard anything as blatantly contradictory as that before. “I’m sorry…” I said, “I thought I dialed the Covid-19 hotline,”

“Yes, this is the Covid-19 hotline,” she affirmed, “But I have no information on Covid-19 or Covid-19 testing.”

“Ok…” I said, unsurely.

“Now, how may I help you?” she asked.

“I don’t know…” I said, my face straining into a confused, red grimace, “…how can you?”

There was a long, almost stunned silence, lasting several seconds, only broken by slight static on the line.

“I can give you information on Flu A, or B,” she suggested, finally.

“Ok,” I said, “sure.” At this point, anything would be progress.

She proceeded to take me through a checklist of flu symptoms, the sort of thing you can (and I had) find on the internet, which already told me that I didn’t have flu symptoms, but rather, textbook Covid-19 ones. She seemed to focus in on the fact that I had a fever, more than anything.

“Well if you’ve had a fever for this long, you need to get some treatment!” she finally said, almost chastising, almost accusing me of not taking my health seriously.

“Well … yeah, I know. That’s why I’m calling,” I said, overtly sarcastic.

“Have you called your doctor?” she said.

I closed my eyes, squinted them hard, shook my head in frustration, and loudly sighed into the phone.

“Don’t be sighing at me like that, motherfucker!” she suddenly growled into the phone, her phony polite attitude dropped, and her inner-city accent burst into the phone with a fury; my sigh apparently hitting a raw nerve. Throughout this call, throughout my many calls, I suppose it didn’t occur to me that she might be just as frustrated with this dysfunctional health care system as I was. I mean, here was a lady who was being asked to staff a Covid-19 hotline with no information on Covid-19 whatsoever, I’m sure she probably had boisterous and openly rebellious things to say about it around their lunchroom.

“Just answer my question!” she demanded. “HAVE-YOU-CALLED-YOUR-DOCTOR!”

“Yes! Yes!” I defended myself. “Several times! They keep telling me to call you!”

“Mmm,” she grunted contemptuously, as if she knew exactly what sort of game was being played here. “Well I will put a flag on your file saying you need to be seen immediately.”

“Ok, wow,” I said, suddenly amazed that somebody was actually doing something for me. “Well, thanks!”

“That’s no problem,” she assured me, “Now you just call your doctor tomorrow and say you called the triage nurse and she said you need to be seen right away, and don’t let them tell you any different!”

“Oh, are you a triage nurse?” I asked.

“Hush, baby,” she said.

“Ok,” I said.

“Then you make sure they see you right away, I got your file updated now,” she said. We exchanged closing pleasantries, and I hung up.

The next day, sure enough, when I called to see my doctor, they immediately suggested I call the cold and flu clinic hotline. I explained to her the days long phone tag I’ve been playing between they two, not the easiest thing to do when short on breath and whacked out on syrup, by the way, and that I finally spoke to a triage nurse who insisted I needed to be seen.

She told me I still had to call the cold and flu clinic, in order to be seen.

In a somewhat short breathed, fever hazy, and manic way, I think I insisted to her that this was the last phone call I was going to make, and she needed to figure this all out for me, right here, right now. Then I started crying.

“Well … I mean, I could preregister you at the clinic and you could just go down there,” she suggested.

“Yes! Good! Fine!” I exclaimed. “That works!”

“Alright, well let’s just do that,” she said and I heard the clicking of a keyboard.

“Was that really that hard?” I asked, wiping away the angry hot tears from my eyes.

“No, I mean, but…” she said, and I swear I could almost feel her shrug through the phone, as she trailed off and didn’t give any further explanation.

She took down my information, and gave me the clinic’s address. I drove down there, noticing that driving isn’t as easy as you might think when you’re short on breath and seeing fractal trailing hallucinations from cough syrup. I pulled into the clinic’s lot, and noticed it wasn’t any sort of purpose built hospital or clinic building, no modern baffling all glass architecture here, but rather looked like a dingy foreclosed house that they hastily had turned into a medical building.

I stepped out of my car, walking towards the clinic door, when I was suddenly halted.

“Stay inside your car, please!” a powerful,

authoritative voice suddenly shouted from across the lot.

I looked over. There was a

security guard. Armed. Looking right at me. His body tensed, his hand resting

on the butt of his pistol. He was wearing surgical gloves, a breathing mask,

and a plastic face shield. It dawned on me they were really taking this

pandemic thing seriously.

I dashed back inside my car. The security guard came over and asked my basic info through my halfway down window. Standing a good five feet away from me, he passed a blue and white surgical mask to me.

“Blue part, in! White part, out! Metal part up!” her barked out with a routine military cadence. “You will wear your mask at all times! Do you understand?” he demanded.

I nodded, and he disappeared.

Half an hour later, he appeared again, and hastily motioned to me through my windshield to get out and follow him.

“Don’t touch anything!” he said, “Don’t open doors, I’ll open them for you!”

I wordlessly agreed as I followed. He quickly ushered me into the building, we passed directly through a waiting room, which was really just an old, vinyl floored living room with a picnic table set up as a reception desk. An elderly woman was in here, arguing with a receptionist that her husband was unable to wear a breath mask, because he was dependent on a ventilator to breath. The receptionist kept repeating that he simply could not come in without a mask, no exceptions.

We cruised right through this room, into the tiny cramped hallways of this small ranch house. Darting around this cramped space were nurses and lab workers wearing fully body purple and yellow paper suits, made out of the same material of the little bib that the dentist straps to your chest, along with purple surgical gloves, and face shields with goggles underneath. They hastily moved up and down the hallway, me jumping out of their way, afraid to touch them, as they bounced from room to room with antlike speed and direction. We passed through what looked like a small lab, full of testing machinery, which was set up in the kitchen area, and the guard pointed me towards an open door, that looked like it used to be a bedroom. I walked in and sat in an old wooden kitchen chair resting there. The floor in this room used to be carpeted but it had been ripped up, bare plywood now, the carpet tack strips still lining the room’s edges. Aside from my kitchen chair, an old, outdated looking doctor’s chair was in one corner, and a desk with a computer was in the other.

I only sat for a few seconds before a fully paper clad nurse came in, and said she was going to swab my nose. “I ain’t gonna’ lie, it sucks,” she said and motioned for me to lean my head back. She jammed an alcohol soaked q tip up my nose, and it felt like she shoved a burning match in. Then she bottled the swab, and left.

Minutes later, a doctor appeared, wearing her full body paper outfit, gloves, and goggles along with plastic face shield. She didn’t greet me, and hurriedly went over my symptoms as she typed into a computer.

“We got to wait for the flu results to come in, officially, but you don’t have the flu,” she told me.

“Yeah, I mean, I wasn’t worried about the flu…” I said, trying to lead her to my area of real concern.

She ignored me, then picked up her scope and stethoscope and examined me. “Definitely something viral,” she said as she sat back down and started typing again.

A nurse peeked her head in and said my flu results were negative.

“Ok,” the doctor nodded, “Definitely something viral,” she repeated, and then looked at me as if I were supposed to say something. She only waited for my response for a second,

“Ok!” she said in that familiar doctor tone when they’re about to wrap the appointment up, “Any other questions you had?”

“Well…” I said, “I mean, I kind of wanted to know if I had Covid-19.”

She only looked at me, not saying a word, for several seconds. I couldn’t gauge her reaction due to the face mask.

“I mean, that’s why I came here,” I said.

Finally she shrugged. “I don’t know what to tell you,” she said, in an impassive, matter-of-fact, and yet somehow honest tone.

“Well, I mean if I have it, I at least want to know,” I said.

“Ok, you have it,” she said, shrugging again.

I didn’t know what to say to that.

“Or you don’t have it,” she said, shrugging yet again. “There’s nothing I can do, there’s no test we have access to. You’ll be better in a week, or…” she trailed off, “Either way, there’s nothing I can do for you that will make a difference.”

I nodded. I suppose, if I were honest with myself and if I could think clearly passed my fever and sleep deprived thoughts, I already knew that she was going to tell me this before I ever went to the clinic. Even if I had it, there’s no treatment, there’s no drugs. They say there isn’t going to be any for months, which really means years.

“Your oxygen level is fine,” she said, “The breathing trouble isn’t good, but you’re not dying. If it gets worse, and I mean way worse, then go to the emergency room,” she said.

I only nodded again, knowing she was just saying what I already knew.

“Ok!” she said in the wrapping-up tone again, and immediately stood up, not waiting for my response, as she went to a corner of the room and ripped off her paper outfit, throwing it into a cardboard box with a biohazard sticker pasted on it that was functioning as a makeshift trashcan. She opened the door, then slathered her bare hands and the doorknob with sanitizer, and disappeared into the hallway.

Two nurses appeared and handed me paperwork, containing information about Covid-19 that I suspected, and later confirmed, was directly copied and pasted off WebMD, urging me to quarantine myself for a full fourteen days. They ushered me out of the dingy home clinic, one behind me, one in front of me opening doors, and I could tell they were both watching me like a hawk, ready to pounce and correct me if I made a wrong step or tried to touch something, as they rushed me out the back door.

Smoke wafted passed my face as I walked outside. I look to my left, and saw the armed security guard, his face protector removed, and his masked pulled down around his neck, as he leaned against the faded slat walls of the clinic/foreclosed house and puffed on a cigarette, his guard totally down now in the erroneous, yet understandably natural assumption that the people leaving the clinic where somehow less infectious than people going in.

“How’d it go?” he nodded to me, in between puffs.

“I don’t know,” I said, “good?”

“Alright,” he nodded. “Well, good luck,” he said, and looked in a different direction away from me, signaling the conversation was over.

As I left, his words stuck with me, and I figured out why on my drive home. That would make a great fancy French name for a medical conglomerate in times like these: “Bonne Chance!”