You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

When I teach workshops on the role of place in fiction writing, there’s an exercise I like to do with my students. I open the workshop by writing the following terms on the board: gender, age, race, era, religion, socio-economic class, country, state, region, season, education, political leaning. I then ask the class to create a character that corresponds to the terms. The responses are always diverse and interesting.

This past summer I was teaching a workshop in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on the role of place in fiction. Spartanburg is a relatively small city in the South Carolina upstate, not too far from the Appalachian Mountains. Everyone in the class was white, and it was comprised primarily of middle-aged men and women at varying stages of their careers, from the well-published to the beginning writer. I tried to hide my surprise when they created the following character based on the terms I’d given them: a highly educated and liberal-minded twenty-five-year-old black female from Canada who is spending the summer driving along the South Carolina coast during the late 1960s. She’s middle class, and she’s a lapsed Catholic. We spent a few minutes coming up with various scenarios about the woman’s life. Why was she in South Carolina? Was she looking for someone? Was she running from someone?

I asked the workshop members to imagine they’re putting gas in their cars when they look up to see this woman’s car parked in front of the gas station. The car’s windows are down, and on their way across the parking lot to pay for their gas they happen to peer inside the car’s windows. What do they see? The things inside the car and the car itself will tell us a lot about the driver. In other words, how much can we know about this woman and her circumstances (i.e. gender, age, race, era, religion, socio-economic class, country, state, region, season, education, political leaning) from her car and the contents therein. I wanted them to tell me what they discovered. I gave the class ten minutes, and they got to work. Here’s what they came up with and how the items portrayed the person to whom they belonged and the circumstances in which she found herself.

Gender: There is an open purse on the passenger’s side. Make-up and vibrant colours of lipstick and blush are inside.

Age: Perhaps the vibrant lipstick may mean the woman is younger, but that’s not certain. But look at the music in the car. A record sleeve of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” is visible in the backseat.

Race: Some people in the class suggested that this could be denoted by a bumper sticker that expressed racial pride. This would make her experience of driving through the segregated South very interesting, and potentially dangerous. Others suggested that perhaps it would be more direct to have her driver’s license visible somewhere in the car.

Era: The model of the car and the car’s condition, combined with the music, are giveaways. Some people suggested having a datebook with the year 1964 stamped on it would be an easier way to denote era.

Religion: There are rosary beads that have fallen from the rear view window and onto the floorboard.

Socio-economic class: She is driving a late-model car, perhaps a Volkswagen Beetle.

Country: Her license plate is Canadian.

State: A South Carolina road map is open and spread across the dash.

Region: There is sand in the driver’s floorboard because she’s been at the beach.

Season: The windows are left down because it is hot outside.

Education: There are any number of books that one could spot in the backseat of the car that would prove the woman to be well-educated and/or highly intelligent. The titles/subjects of the books would also tell us a lot about her interests.

Political leaning: While so many young people were listening to rock ‘n roll and doo-wop, only a socially conscious, progressive minded person would’ve been listening to Sam Cooke’s social justice music at the time of its release.

I stood back from the board and encouraged the group to look at all the signifiers of the woman’s character they’d created without spending a moment describing the woman herself. I said, “Now, when we meet her, think about how much we’ll know about her.” At the same time, consider how much we’ll already know about the era in which she’s living and how she perceives it.

When we think of place, we tend to think of setting alone, and I always warn students and other writers against this. Place is so much more than this. Place shapes and defines us; it limits and inspires us. The season and weather of place dictates what we wear. The political climate of place encourages or challenges or ideas. Perhaps our age, gender, and/or race influences the ways we respond to the place in which we find ourselves.

We’ve all seen the movie where someone comes to after being knocked out or wakes up from a dream or regains consciousness after surgery. The person always asks the same question: Where am I? When readers open a novel or begin a short story, they’re asking the same question, and the sooner the writer can answer that question the quicker the reader can proceed into the story with confidence. In The Art of Fiction, John Gardner calls fiction “a vivid and continuous dream.” As a writer, you’re inviting the reader into the dream, and you don’t want the reader asking questions about where he or she is, what time it is, who he or she is with, and what it feels like. You want readers to proceed into the dream you’ve created with confidence, trusting in the surety of the world you’ve created. Consider how confident you are in your knowledge of the woman whose car you’ve peered into on your way into the gas station. Make your reader this confident as well.

As a writer who often teaches about writing, I always try to take my own advice, and that’s what I did in the opening scene of my new novel This Dark Road to Mercy. Almost immediately the reader will know the same information about my narrator that you knew about the woman whose car is parked outside the gas station.

This Dark Road to Mercy is about a washed-up minor league baseball player who kidnaps his two daughters from a foster home and goes on the run. The opening chapter of the novel is narrated by his oldest daughter, Easter Quillby. Here’s how Easter supplies the information for the same terms I wrote on the board in the workshop on place in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Gender: Female: “My hair was strawberry blonde and straight as a board, and my skin was more likely to burn and freckle than tan. Ruby [her younger sister] was beautiful – she always had been. I looked just like Wade [her father].”

Age: Twelve: “Wade disappeared on us when I was nine, and then he showed up out of nowhere the year I turned twelve.”

Race: White: “She [a young girl named Selena] was black just like most of the kids we stayed with after school and just about all the kids we lived with at the home.”

Era: 1998, the summer of the record-breaking homerun race between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa: “The school year had just started and it was only the third Friday in August, but Mark McGwire already had fifty-one homeruns to Sosa’s forty-eight.”

Religion: She doesn’t mention or infer a religious affiliation, which is interesting in that she’s from the southern United States and the region is so closely affiliated with religion, especially evangelical Protestantism. As a foster child living without parents, perhaps her lack of religious affiliation says as much or more about her than if she claimed to be a stalwart believer.

Socio-economic class: Lower class: “By then I’d spent nearly three years listening to Mom blame him [Wade] for everything from the lights getting turned off to me and Ruby not having new shoes to wear to school […]”

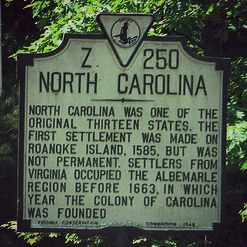

Country: United States: “[…] if I’d known what kind of people were looking for him I never would’ve let him take me and my little sister out of Gastonia, North Carolina, in the first place.”

State: North Carolina (see “Country”)

Region: Southwest North Carolina (see “Country”)

Season: late summer (see “Era”)

Education: middle-school age (see “Age”)

Political leaning: As a poor, white child growing up in the American South, one would assume that Easter is perhaps conservative in her views of race and other social issues. But she and her sister are being raised in a foster home alongside predominantly African American children, and Easter’s boyfriend is an African American boy named Marcus. “He [Marcus] smiled at me, but I looked away like I hadn’t seen him […] When I looked up at Marcus again he was still smiling. I couldn’t help but smile a little bit too […]

By the second page of This Dark Road to Mercy, readers know that Easter Quillby is a twelve-year-old, poor white girl in middle school in Gastonia, North Carolina, who has a crush on an African American boy in the summer of 1998. This is just the beginning of Easter’s story, but she’s given the reader a lot of information about herself in a way that feels organic. She’s telling a story, not sharing her biography or answering questions for an interview. The reader is grounded in place, and the reader is firmly rooted in time. You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen to Easter Quillby over the course of the novel, but you know exactly who she is, and you can feel confident of your footing as the two of you move forward into the dream of fiction.

Litro’s mission is to find the best and most exciting new voices in fiction and non-fiction and give them a platform for their work. To read work from other writers to watch, get our All-Access membership for subscription to our print magazine, membership of our Book Club and unlimited online access.

About Wiley Cash

Wiley Cash is The New York Times best-selling author of A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME and THIS DARK ROAD TO MERCY, which are both available from William Morrow/HarperCollinsPublishers. His stories have appeared in Crab Orchard Review, Roanoke Review and The Carolina Quarterly, and his essays on Southern literature have appeared in American Literary Realism, The South Carolina Review, and other publications. Wiley teaches in the Low-Residency MFA Program in Fiction and Nonfiction Writing at Southern New Hampshire University. A native of North Carolina, he and his wife currently split their time between Morgantown, West Virginia and Wilmington, North Carolina.