You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

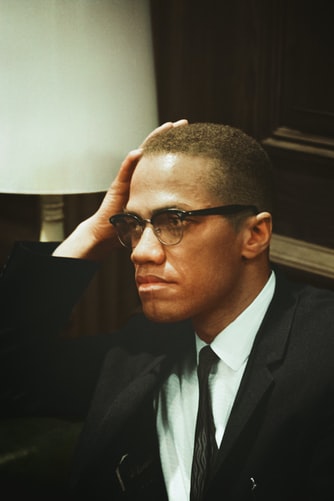

The Dead Are Arising is the first major biography of Malcolm X, and has been twenty-eight years in the making. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Les Payne has attempted to condense hundreds of interviews with Malcolm’s known associates and still-living family, to give us a story that deepens and in places contradicts much of the established narrative about Malcolm’s life. Payne died before the biography could be completed; his daughter and principal research assistant Tamara Payne has finished it from his notes. The book is 523 pages long, plus endnotes, an extensive bibliography, and an appendix that reprints Malcolm’s responses to a questionnaire sent to him by the Islamic Centre of Geneva, which he was working on the week before his assassination. The biography is without doubt a landmark achievement, but it is not without weaknesses.

The most significant of these from a casual reader’s perspective is Payne’s employment of what might be called a very journalistic style. It is not unreasonable to expect that the prose of someone who spent nearly four decades as a print journalist would have acquired a somewhat headline-y flavour; it is, however, frustrating to read so many “tags” for characters and events that we have just been told about. A characteristic example comes from the end of an early chapter recounting the circumstances of the death of Malcom’s father:

Yet the precocious six-year-old first grader had much growing up to do in the shadow of his family’s twin midnight tragedies: the incineration of their home and the death of their father on the capital’s streetcar tracks.

The Dead are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X: 86

The adjectives in this sentence give us a sense of breathlessness but are also unnecessary. “Twin midnight tragedies” veers close to the tabloid, and “six-year-old first grader” is redundant; most first-graders in America are six years old. “Precocious” is committing a good deal of emotional manipulation here, as though Payne feels he needs to put a thumb on the scales of our sympathy for young Malcolm. Most frustratingly, “the incineration of their home and the death of their father” are precisely the events that Payne has just spent the last twenty-three pages describing. The chances that we have forgotten the general outlines of the twin midnight tragedies before the end of the chapter are slim; the repetition makes Payne appear to be either over-egging the pudding, or extremely absentminded.

Emotional manipulation is a general problem, in fact, particularly in the early chapters; a few pages later, Payne writes of “the dishonest scheming of the insurance company”, which acted “with wanton malice against a hapless black widow and her seven children”. The material is strong enough to stand on its own: Malcolm’s mother, Louise, whose upbringing in the West Indies had instilled her in a strong sense of self-worth that the American Black community in the 1930s often found difficult to access in the face of white supremacist terror, was devastated both emotionally and financially by her husband’s death. Her teenage son’s increasingly uncontrollable behaviour (he repeatedly stole housekeeping money meant to provide food for the family, and spent or gambled it all in downtown Lansing) contributed to her eventual breakdown and institutionalisation. It’s a tragic story by any standard. Extra authorial attempts to ensure sympathy land gracelessly, and make the reader feel distrusted.

Louise’s self-belief was the foundation of the Little children’s confidence in the worthiness of their race, and of Malcolm’s later political gospel. Payne has interviewed several of Malcolm’s brothers, most notably Wilfred and Philbert, who were close to him in age; both mention their family’s unusual standing in school, where they were the only Black children attending but were also difficult for white children to pick on, because they all fought back. Louise and her husband Earl were acolytes of Marcus Garvey, whose tenets included Black self-sufficiency, contempt for lighter-skinned Black people and the concept of race-mixing, and education for children that focused on African history and Black achievement. Payne spends a lot of time on these childhood years, and gives us a lot of background. This is clearly done to provide a full picture of the intellectual and social environment into which Malcolm was born, but it’s also easy for the general reader to lose interest, particularly as Payne maintains a high emotional pitch, demanding as much investment and engagement from the reader here as in later sections.

Likewise, chapters detailing Malcolm’s life before prison—the burglary, the affairs with white women, the con tricks, the petty drug dealing—are colourful, giving a detailed picture of Midwestern and East Coast criminal life in the 1930s and ‘40s, but they are not what a person opens a biography of Malcolm X for. The most interesting revelation here for readers seeking insight into Malcolm’s character development is that many interviewees reiterate his primary interest as being the acquisition of power. In his early life, this involved street smarts, charisma, money, and manipulation—sometimes physical abuse—of women. Malcolm’s prison conversion to a more intellectual style of conflict is shown to be a function of his recognition that an older inmate, named Bambry, who was educated, possessed a rhetorical power and depth that Malcolm himself lacked. In Payne’s telling, Malcolm’s autodidactic turn in prison was an attempt to rise to Bambry’s level, to unlock a kind of power that might be more lasting than thuggery.

He was also converted to the Nation of Islam while in prison, though the evangelizing came from his family on the outside: brother Wilfred was an early and zealous convert. The Nation of Islam, as Payne demonstrates, was less a religion or even a sect than a cult. There are details of a foundation myth involving something called the Mother Ship, and the revelation that the entire white race descends from test-tube babies created by a mad Black scientist named Yacub, six thousand years ago. Malcolm seems generally to have avoided discussing these details, in favour of Elijah Muhammad’s advocacy of Black separatism. For years, Malcolm was the national spokesman for the NOI, and adhered strictly to promoting Elijah’s teachings in his public appearances.

The first cracks in his unquestioning devotion appeared when the Georgia Ku Klux Klan reached out to the NOI, asking for a meeting on the grounds that both groups opposed racial integration. (This was virtually the same reason that the Klan and Marcus Garvey had met in the 1920s.) Elijah Muhammad was not present at that meeting; he instructed Malcolm to be deferential to the Klan at all times, while also asking them for help in securing a Black homeland in North America. Deference to whites, particularly the uneducated and unsophisticated men the Klan was fielding, was not part of Malcolm’s playbook. At one point, the Klan’s chief representative, W.S. Fellows, suggested the NOI pass them Martin Luther King Jr.’s Atlanta address; the Klan would arrange for King’s murder, the NOI would keep their hands clean, and they would be both be rid of an integrationist. Malcolm’s instructions were to give the Klan what they wanted, but that would be to make himself an accessory to the murder of a fellow Black man. He refused; Elijah Muhammad was furious.

The rest of the story is the best-known: Malcolm’s discovery that Elijah had fathered ten illegitimate children with his young secretaries, whilst demanding celibacy and strict living for his followers; Elijah’s meetings with increasingly right-wing white supremacist figures, including George Lincoln Rockwell, leader of the American Nazi Party; Malcolm’s defection and conversion to Sunni Islam, including his experience on hajj during which he witnessed white, Arab, light- and dark-skinned Black Muslims all worshipping together; his further travels in Africa asking the leaders of newly decolonized African countries to mention the plight of Black Americans in the United Nations; the FBI’s increasing surveillance and obsession with him as a dangerous Black radical leader; the NOI leadership’s embarrassment as he revealed Elijah Muhammad’s hypocrisy in speeches and writings, and their determination to assassinate him. Payne’s stylistic showmanship serves him better during the second half of the biography: conspiracy, covert operations, murder and a government cover-up lend themselves more readily to dramatic retelling.

The Dead Are Arising won a National Book Award in the US last year, and it is certainly a monumental act of biographical reconstruction. Perhaps its monumental status is part of the problem: for a general reader, Payne’s devotion to detail can drag, and the forward momentum of Malcolm X’s life is often lost amidst minutiae. If, however, the purpose of this book is not to tell a story—if it is, in fact, to provide future biographers and scholars of the civil rights movement with a wealth of information and resources on which to draw—it is a success. Ungainly and subjective phrasing is possibly a small price to pay for a work of this magnitude; I suspect it will depend largely on the reader. Had I not intended to review it, I would have skipped or skimmed the first ten chapters. Having read it all, however, has given me a much clearer picture of the ideas and development of a radical Black icon and his milieu; if that’s of interest to you, too, this book should be on your reading list. Just don’t expect undying prose.

The Dead is Arising: the Life of Malcolm X, by Les Payne and Tamara Payne, is published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin.

About Eleanor Franzen

Eleanor Franzén is a London-based writer and editorial assistant. She blogs about books at Elle Thinks (https://www.ellethinks.wordpress.com).