You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The Americans came down the road at dawn, and the road broke beneath them. There was no explosion—the road just broke away.

“Back from the door,” my father said. He was afraid. My mother, afraid of not only the Americans but my father, too, guided me away from the window where I’d lingered.

“What is it?” she asked.

“The road. It broke away.”

“Will something happen?”

He turned to her, to me, his expression scared and scary.

“Why worry? Don’t ask me!” he snapped. He turned back. After a pause: “It may. Stay inside.” With that, he left us to join to gathering onlookers along the bank of the canal.

I was born in a mud hut in Helmand and spent my birthdays, holidays, weekends and weekdays here, in the fields, with my mother and younger sister. When I was eight, a boy from the neighboring village fell into a canal. The Americans, nearby on foot in all their heavy gear, jumped in and rescued the boy. Three months later, that same man’s daughter fell in, only there was no American patrol this time, and she died. We hear about these things and we blame ourselves. They don’t think we know how to do that, but we do. When I was nine, my father, in a moment of weakness, joined a committee to help repair a bridge. The committee would split the earnings, half of which the Americans paid them in advance. Before work could start, my mother found the letter on the door, posted during the night by one of Them. We weren’t allowed to read it. My father turned pale and quit the committee that morning. Ehsan, my friend two huts down, told me once how his father had received a night letter, how he’d scavenged it from the burn pit before his father returned to light it, how in the crumpled letter They’d threatened his younger sister, Farah, with rape and death if his father spoke again to the Americans about the crops, about the poppies. I remembered Ehsan’s letter when we got ours and wondered if it was the same. How could I not, with my younger sister at my elbow, our mother hovering nervously nearby. Tahmina, six years old then, too young to die for a bridge, too young to die for anything. They wouldn’t let my father work so one of Their own could take his place. When They learned of new contracts, They didn’t stop until They had everything.

“What’s happening, momma?” Tahmina, nine now, tugged at our mother’s dress. “What was that noise?”

“A truck, sweetheart. Stay back. You heard your father.” She spoke louder with him gone. “He said stay back.”

“I wanna look.”

“Are they hurt?” I asked, remembering the time an American Humvee fell into the canal south of us, upside down, trapping and killing three of them. I saw their bodies that day.

“I don’t know. Stay back.”

I looked long at her without blinking. Barely blinking. Once, maybe twice. Trying to impress myself upon her, like father could, but I couldn’t, and she knew it. I turned from her and glared at my sister.

“Father said no,” I told her. “Stay back.”

A pause. “Will They shoot at them?” Tahmina asked. Her eyes were big and afraid.

“Why worry?” I answered, not knowing why I said it like that. “Don’t ask me.” I sat down in the corner. I turned my back to prove I wasn’t interested in the window. I felt her eyes on me. “They may,” I added.

There was a man from my village that circumcised his child at home and made a mistake. The baby’s penis swelled to the size of a small bird and flew away, flew with the child in a helicopter to a hospital somewhere far north by the Americans. The man tried to refuse their help. It was his wife that told the Americans about their son, who begged them to save the infant. When they returned, he beat her. Badly. He was afraid to be gone, gone with his baby and the Americans and no one else, afraid he would be killed because of what They might suspect he might have said about the crops, about the poppies. Like my father, he was cruel when he was afraid. The man received no night letter. During the night, weeks later, he simply disappeared.

“It’s Christmas.”

Minutes had passed in silence. My sister pouted in the corner opposite mine.

“Christmas,” my mother said again.

“What, momma?” Tahmina wondered.

“Those boys. They’re stuck out there on Christmas.” She sat at our small, splintered table and stared at the door, far away.

“Why are they stuck?” Tahmina asked.

No answer. Slowly, my mother rose and stepped toward the window, paused, looked over her shoulder, then cast her eyes down for a moment, reseated herself.

“Never mind.”

I was born the year they came, the Americans. I don’t remember the things adults talk about when they think children aren’t listening. I don’t remember the time when They tortured us and swept away whole families for even looking at the Americans in a way They didn’t like. Since I’ve been able to remember, They’ve had to do this at night, in the darkness when the Americans maybe can’t see Them. During the day, They turn into normal men. That’s the scariest part of Them. They. Not the letters or terror or killing or hate. When it’s day they turn into neighbors and friends and maybe even family—They turn into they; Them turn into them. Our neighbor was a nice man. Was it him who left that letter for my father? Was it him who would have done what the letter threatened, had my father not obeyed?

In our village, before I remember, something like this happened. I overheard it told one night, crouched by my window against the cold dried mud, Ehsan next to me. He shivered in the night air but not from fear, he swore, not from fear but from the cold alone. We heard the men remembering by a fire: A man in our village named Nabi had an older brother, Haaroon, who was injured by a steep fall into a canal and forced to live with his more successful younger brother and his family. Having no wife or children himself, there was no end to Haaroon’s shame, the shame of relying on his younger brother. He left one day, disappeared into the night. They thought him dead. They mourned. They prayed for him five-times-daily beneath the warbling speakers. Taken, they thought. But one night Haaroon returned with two other men, men no one recognized. They dragged the family into the road. Ehsan and I listened as the adults remembered how no one helped Nabi or his family. The whole village would have watched, yet we heard them say “they,” as if, had they been around to stop it, they would have. They were there, our fathers, cowering behind their doors with their wives, our mothers. Nabi’s own brother had stood over him, listening to his younger brother beg for his family’s lives, and then shouted for the village to hear Their warning against aiding infidels. Standing in the dirt with his brother bruised and bloody at his feet, Haaroon had grasped his hair, holding his head up, forcing Nabi to see his beautiful young wife and precious daughter, Haaroon’s sister-in-law and niece, butchered before him—hacked limb-from-limb in large, loping swings of a chipped machete. The murderous Haaroon then cut off his younger brother’s head, sawing with a blade no larger than a kitchen knife. He did this to his own blood not because Nabi helped the infidels (which all knew he hadn’t), but because he’d told Them that Nabi had, that Nabi needed to go, that Nabi and his perfect family needed to be made an example of. Such were the depths of Haaroon’s shame, his wounded pride, his fierce hatred of weakness. Haaroon made Them make sense to me, and when They began to make sense, I feared Them more for it.

“You can look, but stay at the window. When I go out again, stay back.”

It was past noon. All morning, the Americans had been stuck. My father finally returned but only for a meal, which my mother served while he watched us watch. There were dozens of people lining our side of the canal, watching the Americans watch us from their protective oval around the wreck.

“No one was hurt,” my father said, though we didn’t ask.

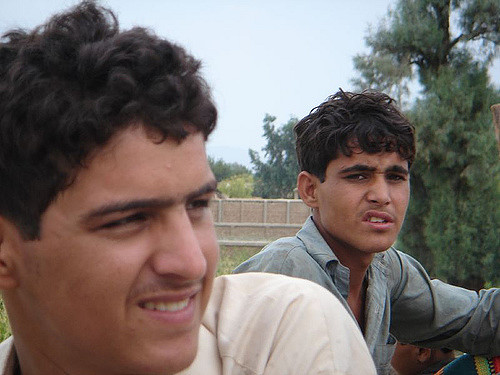

The Americans were young. A few were bored, but others were tense with wide eyes and made a point of not looking right at the crowd, sneaking wary glances instead.

“Who are they?” Tahmina asked.

“Americans. Don’t be silly,” I said.

“I know that. Which Americans? Why do they come, and not others?”

I was silent. I listened to my father chew, hoping when he stopped he’d answer. The silence washed the question away, however. We all let it pass, because none of us knew.

There was a man at the edge of the crowd who I didn’t know, who wasn’t from our village. I watched the villagers try not to watch Him, watched them edge away instead of speaking. I knew not to point Him out. My father would know. Like an animal with a wounded paw, the village felt Outsiders. Like a desperate animal with something in pursuit, we’d learned not to show we felt Them. If we limped—gave away what we knew—They’d come in the night and teach lessons. So no one in the crowd looked at the Man. The Outsider. The Outlier.

“Is it dangerous?” I asked instead, knowing my father knew what I meant, hoping he respected me enough to answer.

He snarled his upper lip at my mother. “This is dirty.” He dropped the cold goat meat on the bare tabletop and shoved away his plate. “Stay back again.”

He left. My mother shepherded us away from the window. This time, Tahmina sat close to me.

“Haamid,” she whispered, “is it dangerous?”

I said nothing. Then, sure my mother couldn’t hear, “it’s only dangerous when they stop watching.”

“When who?”

“The people. Our neighbors. Us. By the canal. When danger is coming, they’ll start to go inside.”

“Why?”

“They just know. Quiet now. Nothing will happen.”

My mother, having cleared the table, considered us in silence before sighing back into her chair, facing the door, waiting for something, though I knew not what.

Later in the evening, when the air was cold and the sun beyond the horizon, I lay in bed and listened for explosions. At night the sound carried. I would guess the distance. Sometimes when everyone was sound asleep I would creep to the window and watch the flares. All night, for miles in every direction, distant flares of bright white and red and green and blue would fizzle in the sky and dissolve into the starry blackness. Other times, blinking lights gliding in wide arcs or, sometimes, just the faint hum of invisible propellers.

They’d come late in the day with the biggest truck the Americans had, one with a line that pulled the monstrous Humvee from the broken roadside like a toy. They’d spent all day—Christmas, my mother had said—there on the road, watching and waiting for evil to happen. When they left, our casually invisible Outsider left and rejoined Them somewhere. I watched through the window from afar as the villagers dispersed and realized the Outsider was most likely not alone: He was simply not local. A village held hostage by uncertainty—not knowing who among them was watching, waiting for a sign of betrayal, not knowing if their husbands knew the Outlier, if they lied when they whispered no, they didn’t.

Haaroon. That night I listened to my father breathe as he slept, and I thought of Haaroon and wondered about my own father. Sometimes, other nights, I would lay awake and think about Haaroon, and I would wonder about myself.

They left and darkness fell as normal, Christmas or not; the distant reports of gunpowder peppered the silent night.

About Danny Judge

Danny Judge’s short fiction has appeared in many literary journals, most recently Twisted Vine, Flash Fiction Magazine, Burningword, and Lunch Ticket, for which he is nominated for a 2016 Pushcart Prize. He is a freelance copywriter and the founding Editor of The Indianola Review, a quarterly print journal.