You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

She was a rather peculiar woman, who lived alone. Life lingered in her slipper shuffles across carpeted rooms. Her home was plumped silent, the solitary loomed. Her purple slippers were worn but the unblinking embroidery was still beady eyed, a clutch of flowers sprung on the ankle side in a burst of pink seed-sized petals, flecked with a stitch of green leaf. The interior sole had taken the shape of her feet, the compressed impression of each toe to cushion her tread, careful and slow. She skirted around carpet lips and stepped over thresholds, and cautiously bordered the perimeter of rugs. All as if she feared getting her feet wet, as if she was playing with crashing waves, tempted ever closer and closer as the sea drew in backwash, scuttling a rattling retreat of pebbles, grinding in a hurry from the outlet of swash.

Maybe, in these slipper shuffles she was reminded of the sea. The crush of the carpet, the hush of the waves, a flash of whitewash torn by the crackle break. Caught under the familiarity of this sound, she struggled against the currents of memory. Her bare feet pinching through the pebbles, the scattering of larger ones and smaller ones, rounder ones, and more jagged ones, each a paint blob from a pallet of grey. Amidst the shingle, a spike of twig or splintered driftwood stuck out smooth, as well as a prickling of brittle seaweed, dried to a salty crisp. Her feet were nipped by the chill of the breeze brushed in from the sea. The stones no longer lukewarm from the sun’s heat, they had cooled cold like forgotten tea. She remembered making her way back up the beach, away from the creeping tide that tried to clip her heel or trip up her feet.

*

Having reached the kitchen, waddling in her wary walk, she praised the kettle. In wrapping her wrinkled fingers around its handle and raising it from its cradle, she clipped back the lid to fill its body with water from the tap. In clicking the kettle to boil, she clung on to the edge of the countertop to steady herself, to steal a breath or two, blinking her eyes to a close. Upon opening them again, she noticed the crumbs that sprinkled the floor, strewn loose from the bread board as she had plucked two slices of bread from her ready cut loaf that morning.

She would need to hoover again. She could never control the crumbs, her balance was slightly off, and so they were often brushed onto the floor, due to a lagging elbow or drooping sleeve, when preparing breakfast or lunch. Other times, the crumbs would roll and disperse when cleaning the wooden board, trying to angle it right, to sweep the bits down the sink. The same would happen when she cooked, or ate, and then cleared her plate. The lack of steadiness in her hands and the imbalance of her gait, only saw the dusting of crumbs everywhere. But she kept the place as tidy as she could, always clearing up after herself and hoovering. Lugging the hoover around the house in a trail of snaking cord, feebly pushing, and pulling and directing the hoover head over the mess, sucking up the morsels and the crumbs that had fallen to the floor, like punctuation sunk from her swallowed sentences and words unsaid.

*

The kettle clicked, huffing in clouds of steam as the water bubbled to a boil. She leaned forwards and hooked her finger around the crook of her mug, bringing it towards her and laying it down on the counter with a hiccup. The mug was a frail white, rather narrow and sitting upright before it curved outward slightly at the lip, as if an unfurling petal curling at the tip. A dainty daffodil clung to its outer edge; yellow petals webbed behind a trumpet of subtle orange as its stem sprouted leaves of green. This flower mellows in different notes of memory each time within her mind, as if subtly nodding its head in reminisce. She would remember how the daffodils once licked up the light on her windowsill in a radiant golden glow, wiping her face into a smile for she had always been gifted them long ago. The kind lady at number six used to present her with a sprightly bunch when she brought over freshly baked bread in the spring. Many springs had spiralled into summer since and the lady moved out of number six, she knew no one in the street as well now.

*

Still tender from the memory she sighed with the steaming of the kettle, then went to pluck a tea bag from the pot labelled ‘Te’, gently lifting, and replacing the lid. Having popped the tea bag in her mug she steadily clutched at the kettle handle to drown the bag in boiled water and let it stew. Having set the kettle back down in its cradle she ventured to take the milk out of the fridge. The fridge hummed cool, opening it breathed a rush of goose bumps up her arms in a chill, then it coughed closed, and the milk was transported to the countertop and placed next to the proud mug. In unscrewing the milk cap her fingers tingled in relief. She had opened the milk. She could no longer open jam jars, no one knew about the unopened jam jars in her cupboard.

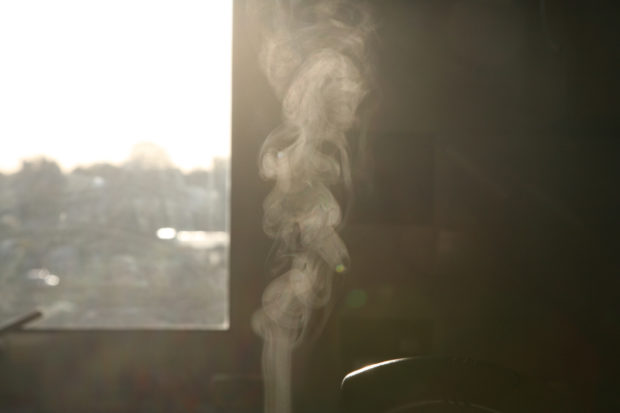

This apprehension of increasing physical inability clouded her mind like the splash of milk she poured in her tea. But no, she insisted in a slight shake of the head, she would not let this bother her, not like the crumbs. She stirred away the thought in the circling motions of her teaspoon, whirling around her tea, dimpling at the centre like the eye of a clock. She extracted the teaspoon with a quick clink on the mug’s lip, then placed it on the draining board that jutted out beside the sink. More swiftly than it was obtained, she turned on her heel once more and placed the milk back in the fridge, its door closing in a limp clap. At the very same moment, she heard the letterbox flap. And so began, in her purple slipper tread of trepidation, tiptoeing the carpet brink, towards the front door. She forgot all about her tea, stranded silent in the kitchen’s gleam, it uncurled ringlets of steam, rising into her loneliness before evaporating like a phantom of the woman she had once been.

About Imogen Davies

Imogen Davies is a 21-year-old Welsh writer from Aberystwyth, studying French, Spanish, and Catalan at university. Recently returned from a year abroad, she misses the sunshine and mornings spent reading on the terrace. Her poetry has appeared in Streetcake’s Experimental Writing Prize Anthology 2022, Acumen Young Poets, and the Stratford Literary Festival’s Young Poets Collection 2022.