You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Shelly is sitting in the far corner of the breakfast room, drinking coffee from a white mug. After each sip, she grimaces. Hotel coffee tastes like shit, but she drinks it anyway because it’s a big day today and she didn’t sleep well the night before.

She’s staring across the room at Shelley. Shelley is in line by the buffet table, waiting for the man in front to move along so she can get to the croissants and little pots of butter. That’s how it seems to Shelly, anyway.

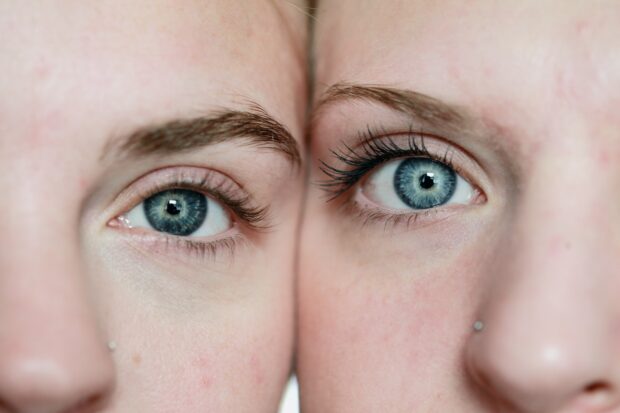

They look like each other, Shelly and Shelley. That’s more noticeable this morning. They have different coloured hair – Shelly’s is dark brown like a bar of Cadbury’s Bournville whilst Shelley’s is straw blonde – but they style it the same way, in a bob. And they’re both slight, pale-skinned and pretty. Today they’re wearing summer dresses. Shelly’s is dark blue; Shelley’s is pale yellow.

‘Hey, Shelley! Over here.’

Shelley turns and spots Shelly. She grins her stupid grin and comes over.

‘O.M.G.,’ she says. ‘Hello again, Twinny.’

She pulls back a chair and sits opposite Shelly. Wasn’t invited to, but never mind. ‘I’d half-thought I dreamt you up,’ she says.

Shelly forces a smile. Only a small one.

‘Yeah. I can hardly believe you’re real myself.’

They met yesterday, a bit before six pm. Shelly returned to the hotel after meeting Jackson for dinner and there Shelley was, standing inside her bedroom like some ghostly apparition.

‘Who are you?’ Shelly demanded by the door.

‘I’m Shelley,’ Shelley said.

‘I’m Shelly,’ was Shelly’s reply. ‘What are you doing in my room?’

Shelley held up a white key card. ‘This is my room,’ she said.

‘Look around you,’ said Shelly. ‘See all this stuff? That’s my coat. That’s my suitcase. This is my room.’

Shelley gave a goofy smile she probably thought was endearing and said: ‘I was confused by all this stuff. But listen, I was checked into this room at reception. That’s how I have the key card.’

They took the elevator to the lobby together and spoke to the lady behind the desk. They passed their phones to her so she could look at their booking details. She seemed amazed.

‘You have the same names.’

‘We know,’ Shelly said.

‘No,’ said the lady. ‘Look. Besides one letter, you have the exact same names. Shelly and Shelley Martha Taylor.’

‘O.M.G.,’ said Shelley. ‘That’s crazy.’

‘But what about my room?’ Shelly asked. ‘Why was she in my room?’

The lady tapped at her keyboard, moved her mouse around a bit.

‘I’m guessing one of my colleagues was a bit confused when you asked to be checked in.’

She was talking to Shelley at this point.

‘They probably assumed you were Shelly here, and thought you’d checked in a couple days before. So they gave you a spare key card to the room they thought was already yours.’

‘Makes sense,’ Shelley said.

It didn’t track with Shelly, but whatever. ‘Can you sort it?’ she asked.

‘Yes, of course.’

As the lady tapped away again, Shelley turned to Shelly.

‘Same name, fancy that. Tell me. Your accent. Where’re you from?’

‘Leicester.’

‘No way! Same! You’re not twenty-five, are you?’

‘I am.’

‘I am too! Go on. Date of birth?’

‘Thirtieth of March.’

Shelley took Shelly by both hands.

‘Same! I bet you were born in the LRI too. You were, weren’t you?’

Her mouth was dry. Shelley was right. Shelly turned to the lady. ‘I’m not needed here, am I?’

‘No, no. Just need to sign Shelley here into a different room.’

‘Good.’

And she pulled her hands away from Shelley and sped back to the elevators.

In her room, Shelly paced back and forth. An uncanny feeling followed her, tried to embrace her from behind in a cold hug. She shrugged it off physically, moving her shoulders up and down.

Maybe the experience contributed to her bad night’s sleep. She couldn’t say.

Now, in the breakfast room, Shelly wants to know more about Shelley.

‘I went to St Paul’s. What about you?’

‘For secondary school? English Martyrs. That’s the same Parish, right?’

Shelly ignores her counter-question. ‘Are you Catholic?’ she asks.

‘I don’t really like to label it. Agnostic, I guess?’

Shelly narrows her eyes.

‘What about you?’ Shelley asks.

‘Never mind! Where did you grow up? Exactly?’

Shelley leans back in her chair, eyes wide. ‘Feels like an interrogation!’ she jokes.

Shelly’s face is hot. She doesn’t respond.

‘Look, Shelly,’ Shelley goes on. ‘I promise I’m real and my own person.’ She giggles a little, adds: ‘Not some evil twin.’

‘What’s your job?’

Shelley looks perturbed but still answers. ‘I do a bit of acting,’ she says.

‘What does that mean?’

‘Well, y’know. Work from gig to gig. Bit here, bit there. Small stuff.’

Shelly folds her arms. She can feel the heat in her face dissipating, like a kettle that’s stopped bubbling. She can’t help but smile.

‘What do you do?’ Shelley tries.

‘I’m a painter,’ Shelly says loudly.

‘Ooh. That sounds cool.’

‘You could say that. It’s pretty great doing something creative for a living.’

‘I agree.’

‘Good money too.’

‘Oh really?’

‘For sure.’

‘That’s great.’

‘Difficult to make money working creatively.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yeah. Well, you’d know.’

Shelley smiles and nods her head, as if she missed the barb completely.

‘I have an exhibition opening today,’ Shelly continues. ‘That’s why I’m here.’

Shelley looks to the buffet line then back to Shelly. ‘I’m glad for you,’ she says.

Fuck off, Shelly feels like saying. Instead, she says: ‘Thanks.’ Then they sit there, looking at one another. ‘Okay,’ Shelly says. ‘That’s all. Thanks for your time.’

Shelley bobs her head and leaves the table.

Shelly sets up the exhibition with Jackson and the venue staff. It’s being held in a place called The Blue Building. Shit name, but fitting. It’s a square cube of blue glass in Westminster. Near Churchill’s war rooms. They’re on the second floor.

Shelly calls her pieces Abstract Portraits. They’re dotted around the room on metal easels. Sketchy outlines of people she knows smudged with circles and squares of colour: pale pink and crown gold for mum; dollar green and violent red for Jackson.

She stands and admires her self-portrait once everything’s in place. It’s the first one she painted. A vague shadow of herself sitting side-on. One colour splashed across the canvass. A limitless sky-blue.

Each piece is titled after its model. Mum. Jackson. Shelly.

No.

She grabs the title card attached to the easel and brings it to eye level. It says Shelley, not Shelly.

Jackson appears and lets his hand wander. It reaches her bum and Shelly shakes him off.

‘Jackson, what the fuck is this?’

‘What?’

‘This. This title is wrong. You’ve misspelled my name.’

‘Didn’t you print out the title cards?’

‘Fuck off, Jackson. I didn’t misspell my own name.’

He grins and touches her back.

‘Chill, woman. It’s no biggie.’ His hand rubs her back in circles. ‘This is a big day. Some important people are coming. Critics. You can’t be worked up.’

She shrugs him off again then sticks the title card back onto the easel.

‘You just hang about, look pretty, answer questions. Let me network for you. Okay?’

She doesn’t answer.

‘Okay?’

‘Yes. Okay.’

He smiles and moves away to help the staff put out the snacks.

And the exhibition goes well, in the end. Lots of people come throughout the day, including critics. One person – just someone off the street, Shelly thinks – says it’s like Shelly unearthed something true about her subjects, as opposed to painted something true. ‘Remarkable,’ one lady comments. ‘She could be going places,’ someone from The Guardian tells Jackson.

Shelly overhears one negative comment, near the end of the day. It’s from an older gentleman. Maybe a critic, maybe not. She’s leaning against the wall next to the entrance doors, drinking shit coffee from a Styrofoam cup and saying: ‘Thanks for coming,’ to everyone who passes through the doors, and this guy says: ‘Thoughtful but flailing,’ aloud to himself. Whatever the fuck that means.

Shelly shakes her head. Whatever.

‘Place shuts in an hour,’ says Jackson. He has a roll of binbags in hand and tears one off to pass to her. He moves to the side wall and begins chucking paper plates and bowls of uneaten crisps into his bag. Still thinking about the comment, Shelly goes to follow.

That’s when, across the room, she sees her.

Shelley M Taylor.

Standing by the self-portrait.

Examining it.

Smiling.

The uncanny feeling of the night before grabs hold of Shelly, icy arms wrapping around her chest. She takes a step forwards. ‘What the hell?’ she mutters to herself. ‘What the hell?’

The icy feeling melts. ‘What the hell?’ she says, louder. She drops the binbag and stalks across the room. Shelley takes a step back from the portrait, turns and says something to a guy standing nearby. He says something back, then takes out his phone. Shelley leans into him, they pose with the portrait, and he takes a selfie. Shelly can hear him as she approaches: ‘Thank you, thank you.’ And he moves off, past Shelly and towards the exit.

That’s when Shelley sees Shelly.

‘Twinny! What a great exhibition.’

Shelly reaches the portrait, legs heavy. She doesn’t speak. Only stares. Shelley really looks like a doppelgänger now. The only difference is hair colour.

‘You sorta hinted you were good,’ Shelley continues, ‘but I didn’t imagine this good. Incredible!’

‘What are you doing here?’

She shrugs. ‘Just a coincidence,’ she replies. ‘I was nearby and saw the sign.’

Shelly makes the beginnings of a word, a ‘W’ sound, but it dies away.

‘You okay, Hun? Like you’ve seen a ghost.’

Shelly blinks. Shakes her head. She wipes her forehead and realises she’s sweating. ‘Fine,’ she says. ‘Stomach-ache.’

There’s an awkward silence. Shelley fills it by nodding at the self-portrait of Shelly and saying: ‘Looks like me, eh?’

‘Well, it’s not,’ Shelly snaps.

Shelley smiles apologetically. Both set of eyes wander to the title card.

Shelly sips her coffee. Affects composure. ‘The place is closing soon,’ she says. ‘You’ll have to leave.’

And before Shelley can reply, she rushes over to help Jackson clear away the snacks.

Shelly and Jackson drink in the hotel bar after the exhibition. It’s not dark yet. Through the windows, above the city, the sky is a dim cobalt weaved with ribbons of sunset pink. Vodka tonics sit on the table in front of them. They’re both on their phones.

Shelly googles Shelley M. Taylor. Pictures of her own artwork comes up, and so does her website, and she realises she searched Shelly M. Taylor, not Shelley.

‘Fuck’s sake,’ she hisses.

Jackson glances at her, laughs in that way of his, then returns to his phone screen.

Shelley M. Taylor. Actor. Google Images shows screenshots of Shelley in lots of different clothes – she’s been on T.V. Even has a Wikipedia page. Shelly clicks the link to the Wikipedia article and reads. The woman’s been nominated for things. Not for major awards, but still. She’s been in the West End since she was a teenager. In a show now called Glory is a Drag.

Shelly drops her phone to the table like she’s been told a disgusting fact about it. ‘Fuck me,’ she says.

Jackson looks up again. So do people at the surrounding tables. ‘What is wrong with you?’ he asks through a chuckle.

She takes a long swig from her drink then says: ‘D’you wanna see a show?’

‘A show?’

‘Yeah. Theatre.’

Jackson puts his phone on the table. ‘Like a date?’

She doesn’t reply.

‘Because I thought you said you didn’t want to do that anymore.’

‘Not a date,’ Shelly confirms.

‘Then no, I don’t really want to see a show.’ He picks up his phone and grins slyly. ‘Unless we you-know-what afterwards. Haven’t done that in a while.’

‘You’re a pig.’

He laughs. Always laughing at her. She studies the black and grey stubble along his jawline and feels a wave of hatred. It’s concurrent. Hatred for him and hatred for herself.

She can’t figure out where these emotions are coming from.

Glory is a Drag is on at the Pluto Theatre the next evening. It’s a small venue. Not much to look at from the outside. Just off a main road. Grey brick painted white. Peeling. But it’s got character. A real presence that makes you think: this place has seen some things.

It’s not hard to get tickets. Shelly sits in the second row. The seats are that classic theatre kind, red velvet and they fold up. Capacity can’t be much higher than three hundred. Before the show starts, she buys a coffee in the foyer. It’s made in a French press and is delicious – scalding and tastes exactly like it smells.

Glory is a Drag is an austere production. It’s all about the acting. Shelley plays a mother who falls in love with a sailor. Her son and his friends idealise the sailor as the pinnacle of manliness. But after discovering him to be a sappy romantic, they inflict a brutal, murderous revenge. It’s weird. Based on a book, apparently. But the cast sells it. Especially Shelley.

There’s this one part Shelly can’t help but admire. It’s in Act One. Shelley’s character and the sailor character are sharing breakfast after their first time sleeping together. And Shelley, through both her dialogue and moments of silence, somehow portrays a real tapestry of intent and emotion. At once, her character is clearly taken with the sailor. But she’s also sitting and eating with him in order to prove to herself that the night before was not a mistake. And, subtly, the character’s mind is on her son, as well, and on what he would think of the sailor.

Shelly’s eyes stay locked to Shelley’s face throughout this scene. She watches her lips move up and down, the eyebrows rise and fall. And she can’t believe the woman on stage is the same goofy woman as the one she met in the hotel. She imagines what Shelley’s Abstract Portrait would look like and all she can think of is the portrait of herself smothered in limitless sky-blue, sitting on the second floor of the Blue Building on its metal easel. She shakes her head to scatter the thoughts out of mind.

At the end of the show, the curtains close, the audience claps, and Shelly’s fists turn white. Shelley spots Shelly during her curtain call. There’s a twinkle in her eye and she holds up a finger as if to say: Wait there. I’ll be with you in a moment. So Shelly does. The audience filters out and cleaners come in, and Shelly remains in her seat.

The theatre’s silence is conspicuous, broken by only the occasional ruffle of a binbag. Shelley appears back on stage in her own clothes: jeans, a white blouse. She gestures for Shelly to join her.

They sit on stage with their feet dangling off the edge. In the upper balcony to their right, a cleaner’s vacuum roars.

‘You know how it is,’ Shelly lies when Shelley asks what she’s doing here. ‘You saw me and my work. Thought I’d come see you and yours.’

‘And what’d you think? Did you like it?’

The room lights are on, colour a streetlamp orange. But they’re dim. Some of Shelley’s face is cast in shadow.

‘Yes,’ Shelly says. ‘It was brilliant. You were brilliant.’

Shelley beams.

‘So,’ Shelly goes on. ‘I’m confused. If you’re an actor working in London, why are you staying in the hotel?’

‘Oh, my flat flooded, is all. Thought I’d live in luxury whilst I wait for the all-clear.’

Shelly raises her head. She looks up at the ceiling. It’s white, decorated with golden circular ridges patterned like a flower. Very pretty.

‘It’s great, isn’t it?’ says Shelley. ‘The Pluto?’

‘Hm? Oh. It is, yeah. Beautiful building.’

‘When I work here. I dunno. A place like this spurs you on. Something magical flows through you. It’s special.’

‘You speak about it almost in religious terms.’

Shelley looks embarrassed. ‘Well, I dunno. You probably feel the same way about your studio. Your exhibitions’.

Shelly frowns. ‘Not exactly,’ she says. Then: ‘Seeing you about, this phantom doppelgänger. It’s like I’m living in some simulation or something.’

‘Sorry,’ Shelley says with a laugh. Then she picks up on Shelly’s distress, because she places a hand on her shoulder and says: ‘Hey, try to see it the way I see it. Just this really cool coincidence. You’re my Twinny.’

‘I can’t. Because seeing you makes me feel…’ and she trails off.

Shelley shuffles in place. ‘I don’t really know what I can do for you, Shelly,’ she says. ‘Besides stopping existing.’

They make eye contact.

‘You haven’t come here to kill me, have you, Shelly?’

Eye contact holds. Tension deflates like air from the end of a balloon as they laugh.

Shelly’s gaze falls then and happens to land on Shelley’s hand, pressed against the stage. There’s a gold ring on her finger.

‘Wait. You didn’t have that on before.’

Shelley seems confused but then understands. ‘This?’ she says, raising her finger. ‘You mean yesterday? Yeah, I had an audition yesterday so took it off. The character’s a teenager, so I don’t know. Stupid, but I wanted to project youth.’

‘You’re married?’

‘Engaged.’

Shelley says this then waits. Shelly leans back as if recoiling from a slap to the face. Seeing no response is coming, Shelley starts up again.

‘Yeah, he’s called Joshua. We met at the Old Vic – that’s our drama school, and we’ve…’

‘And this film audition?’

Shelley swallows back her words, looking bemused. Shelly doesn’t care. Her eyes are screaming: Come on, bitch. Tell me.

‘Yeah, um. Yeah. It was for a film.’

‘Hollywood?’

‘Yes. Hollywood.’ Shelley pauses, trying to anticipate Shelly’s next interruption, but it doesn’t come. She speaks on. ‘I can’t say much, but it’d be in a role alongside – wait for it – Olivia Coleman. O.M.G., it’s crazy. She wasn’t at the audition, obviously, but…’

‘Oh, fuck off!’

‘I’m sorry?’

Shelly stands. ‘Who are you?’ she demands. ‘Where did you come from?’

Shelley stands too. ‘I don’t understand,’ she says.

Shelly reaches out. She grabs Shelley by the wrist and squeezes.

‘Ow. You’re hurting me.’

She can’t let go, must hold tight a little longer.

‘Please, Shelly. Get off.’

A little longer.

Shelley draws back her hand as if to strike out. Shelly releases, turns, jumps off stage, and flees down the middle aisle. Her temples pulse and her body feels light, like it’s not there at all.

There’s a shout: ‘Shelly!’

Ignored.

Outside the theatre, tears come to her eyes.

Shelly invites Jackson over that night and lets him fuck her. She sometimes does that. He likes to choke her and call her a slut, and sometimes she lets him do that as well. Probably a bad idea, fucking her manager. She’s put a stop to it many times. But it’s just one of those things.

The whole time they’re at it, she thinks of that old man at her exhibition. Weird to do during sex, but she can’t help it. Thoughtful but flailing. Thoughtful but flailing. The words run through her mind like a bad omen. You couldn’t describe Shelley’s performance that way. There’s one difference between them.

Jackson pulls away, hops onto the carpet, and pads into the en suite bathroom. The light flickers to life and the extractor fan roars. Shelly remains on her hands and knees on the bed. A thought strikes her so suddenly it’s like some invisible, intelligent other reached out and placed it in her mind for her.

Maybe Jackson’s only her manager so he can fuck her.

She falls to her back, puts a pillow between her legs, and curls into a foetal position. A second thought as she listens to Jackson’s pee hitting toilet water. Maybe this is the highlight of her career. This first, this only exhibition.

The Blue Building.

This five-star hotel.

Her eyes draw to a tray on the bedside table. They had ordered room service. Jackson’s half-eaten sandwich sits on a white, paper plate. Next to it is the coffee Shelly asked for. She had one sip then left it. The coffee really is done awfully here. She laughs lightly at the thought, then buries her face into the covers and thinks of someplace else.

About Sam Dawson

Sam is a writer based in Leicestershire, U.K.. His work has been published by Banditfiction, Audio Arcadia, Unstamatic Magazine, the Syncopation Literary Journal, and elsewhere. He has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Leicester.