You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I parked my car and worried about leaving it and worried about the privilege of being able to leave it. I worried about my own worrying about it, and what it says about me – my doors never used to lock. Conscious of the tenderness of knuckle and how I knocked – did it sound like the cops? – I wondered if I should even think this or if its impact transcended trope? (I should not have to rehash for you the catalysts of the Black Lives Matter movement.) When I knocked, I made its noise into a sort of music, so its rhythm wouldn’t sound alarming: tat-tat tata-tat-tat tat-tat. Even when coming from loved ones, a knock is never welcoming; its thuds excite or concern us more than they calm us. The sounds are alerting. Alarming. An issue to be dealt with.

In this Baton Rouge district, some of the houses had no doorbells. Sometimes, the doorbells were taped over with blue masking or black electrical tape. Sometimes, the outer coverings were broken so that the light shined behind, but I wouldn’t press them for fear of being shocked. Sometimes, a second doorbell with a small camera had been added. These doorbells were black and lit up blue as they rang and they sang a small, sharp tune and surely watched me. Sometimes, the doorbells didn’t make a sound, so I pressed my ear to the door to listen and knocked after and felt the tenderness in my knuckle again. So many of the doorbells didn’t work or weren’t there that a knot formed in my knuckle. Sometimes there was a camera above the door and sometimes in place of the camera there was a piece of paper that said, “Smile, You Are On Camera” or “We Are Videotaping You Steal and Will be Sharing with the Police.”

Some of the doors had second, outer metal doors over them. These were a pattern of strips and rods through which I could see the real door and through which my hand sometimes fit to knock on the real door. Sometimes I had to knock on the steel frames, which made a low sound that people barely ever answered to, and sometimes I had to knock on the mesh patterns between the frames, which made a loud rattling sound which startled even me. Sometimes near the door there were signs that said, “KNOCK LOUD” or “Leave packages around back.” Sometimes the house had a gate that I could walk through to get to the door and sometimes the gate was locked so that I had to slip the flyer on the gate and say hello and hope that someone was home.

*

The sidewalk broke away and gave to grass, the yards to rock and mud. A Styrofoam sonic cup pooled its remaining blue wastes of sugar juice. I told you that I parked my car and left it, and as I walked, I watched a man enter shirtless into his house – he was taller than me with broad shoulders and a bald head. His skin shone pale and white and flexed black tattoos on his back and arms. I walked past his home, since it was not listed on the canvassing app on my phone, and I knocked without answer at his neighbor’s door. As I moved along, a small pickup truck idled at the street-edge of a driveway a few houses down. The truck was white, with a rust-red fender, and the woman inside watched me. She had been watching every house I knocked on. Her hands rested on the steering-wheel as I approached.

“Hello. I’m just here canvassing for the upcoming school board election.” She wore a white shirt with no logo, not bright but not torn. Despite leaning all the way back in the seat, her stomach pressed into the steering wheel. Her eyes, wide. Her hair, stringy. Even though she was not on my list, in order to defuse her I talked about the candidate I was canvassing for and about how the incumbent had been on the job for awhile despite the fact that the schools keep underperforming. It was my standard spiel.

“Me and my mother have been here twenty years and watched it go to shit,” she said. “It’s disgusting. See that man over there?” She pointed to the white man with the tattoos. “He’s the biggest drug dealer around. And down the street, Mrs. X’s daughter has special needs. The blacks use her as a sex toy.” I nodded. There was nothing more to say to this woman, really. She drove off with her truck clunking and my knuckle tender from knocking.

*

Further down the street, I knocked on another house. The couple that lived there were in their eighties, and so I waited awhile longer, laid a flier on the door, and left. As I walked across the street, I heard a door opening and a man, voice measured and low, muttering hello behind me. “I saw you leave something on my door.”

The man stood shorter than me, and I am a short man. His body drew thin at the shoulders and wrists, the way older people can. He held a rake and covered his head in a sun hat with a wide brim. Suspenders supported his tan khakis. I gave him another flier since he did not bring the other from the door. I asked him who he planned on voting for. I talked with him about the schools’ poor performance in the entire city, not just in this district. He looked over the photograph of the candidate.

“At my age,” he said, “I’m not against anyone.”

Okay. Wait for it. Try to smile.

He continued, “You can’t be against anyone at my age.” He held an expression of half hope, half fear, anxious about whether I would judge him.

“But really, what can you do?” he said. “They’ve only made it this far and been around this long. How much farther can we expect them to get, really?” His hand was shaking, slightly. I suspected from age and not nervousness. I tried to smile. I tried to tell him about the candidate’s platforms. I asked him if his wife was available to speak and I asked him if he would like some help raking his yard. He told me no thanks and that he would look over the flier and consider voting for my candidate.

*

I know that my being white allows me the privilege of being patient with a man whose culture has engrained in him a racist worldview and an inherent bias against minorities, women, and other ethnicities. But I also know of Daryl Davis, who dialogued with Roger Kelly, the Grand Dragon of the KKK in Maryland, for so long that the two men became friends and Kelly eventually quit the Klan and gave Davis his robe. This greatly diminished the presence of the KKK in Maryland. To be clear, I am not advocating for anyone to speak with Klansman. No one should speak with Klansman. Davis is lucky he isn’t dead. But it worked. On the other hand, I also remember an image from Facebook. In the picture, a young and thin black man holds a sign at the Woman’s March. The sign read, “We’ll See All You Nice White Ladies At The Black Lives Matter Rally, Right?” I know that the issue requires both patience and pressure.

This is an essay on canvassing and the state of schools in Louisiana. But the essay is also about race because every essay ever written in the United States is about race. If you don’t realize that, you’re part of the problem.

*

When clouds covered the sun, and a slight drizzle, so thin it almost formed in fog, pearled the screen of my phone, I tucked an umbrella into my armpit and grew thankful that the heat had abated. Some days the temperature made me sweat in places that people living in the north never realize you could feel sweat in. And this was fall, mind you. This wasn’t even summer.

I knocked on the outer security grate of a red brick house and no one answered. The doorbell either didn’t work or made a sound inaudible behind the door. As I turned, I looked across the street to the end of a lawn with no sidewalk where someone had piled tires, broken or shattered windows, an old printer, and a couch. The couch was leather, black with the front faded and ripped to grey. The house behind it was tan with a black roof shaded umber by leaves and dirt. On the roof, a grey satellite dish pointed towards the constellations above this very down-to-earth property where someone may have resided or someone may have abandoned.

I snapped a picture on my phone, and as I turned around the block, since the house sat on the corner lot, I heard men behind the fenced-in yard, not visible from where I stood earlier. “You’re on camera, too.”

“Excuse me?” I didn’t think anyone was home, since no one answered.

“We’ve got picture of you, too. You and the Feds.”

In the yard, three men huddled. The one calling me out sat in the driver’s side of a newly restored Lincoln with bright rims. Beside the car, two men stood, one with a small glass bottle of gin in his hand. It was before noon.

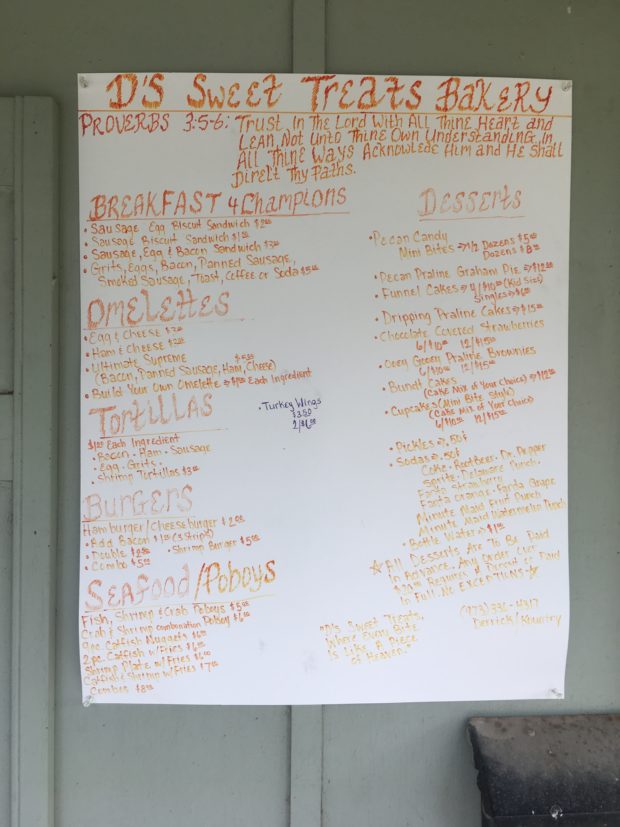

The neighborhoods in this district wavered from run-down to classic suburbia. Tall, weedy grass to manicured lawns with carefully carved hedges. On one street, I saw a house with plasterboard for windows. Someone had written in chalk on the plasterboard, “For rent, call 225…” On another street, I saw a bonsai tree larger than any I’ve witnessed outside of museums. White stone lions pillared each side of one driveway. Several broken-down cars were the statues in another driveway. One house held a large banner written in black and red paint. The font varied in styles from cursive to gothic. It read, “Happy Birthday,” “We Gain Johnson,” “Asia Kim,” “Love Won!” and “Engagement Party.” I couldn’t quite make sense of it. At another house, a sign beside the door listed in orange marker the prices of meals. Patrons could get several “Breakfast 4 Champions” platters, such as a grits, eggs, and sausage plate with coffee for $5. A fish, shrimp, or crab poboy, also $5. Hamburgers or cheeseburgers were $2. That was not a typo. Desserts ranged from pecan candies to bundt cakes. At the top of the menu, the owner had written out proverbs 3:5–6, “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart and lean not unto thine own understanding. In all thine ways acknowledge him and he shall direct thy paths.” Their slogan read, “Where every bite is like a slice of heaven.”

*

In Louisiana, students in grade school take the LEAP test every year, which assesses their skills in English, Math, and Social Studies. The test is scored through five levels: advanced, mastery, basic, approaching basic, and unsatisfactory. In order for a student to be prepared for the next grade level, he or she must meet the level of mastery. However, for the last three years, little progress has been made. In 2018, only 34 percent of third-through-eighth graders met this requirement. When high-school students were added, only 43 percent of the students scored mastery in English, and only 33 percent of the students met this benchmark in Math, according to The Advocate. In U.S. News and World Reports’ “Best States for PreK-12” rankings, Louisiana comes in at 45. Wallethub, whose study factors in funding, class size, instructor credentials and safety along with performance, rates Louisiana at 50 (out of 51, since D.C. is included).

Aware of the poor state of their schools, the citizens I met voiced concern. One woman who worked at the post office wanted to know what the candidate would do about the LEAP Test. She worried that the state’s requirement that students pass the test by a certain try held kids back and shaped the way teachers interact with kids in the classroom. Another woman wanted to know what the candidate would do to better the lives and working conditions of support workers like bus drivers and janitors. Everyone talks about the teachers, she said, but they aren’t the only ones working with these kids.

As I answered a nineteen-year-old’s questions about her polling place, one of her relatives, who didn’t live in the district, swayed and proclaimed that politicians promise anything but never deliver. She said she’d called her senator about burying her husband, but no one would help her.

Some people didn’t answer the door even though I could hear them watching television or talking or moving around. Sometimes the door would be open and I could see them through the inner screen door, watching TV and ignoring me. Most yelled, “Who is it?” through the door. Some shouted “Get off my property,” or “Not interested” without ever knowing why I was there. Some said, “We don’t vote,” or “I’m going to vote” in a tone as if I’d expected them not to participate. A few teenagers told me with pride how they were going to vote for the first time. This district resembled most districts in the U.S. Some people were involved in their community and some weren’t, for reasons both personal and a product of our national culture. Some held hope, while others had given up or never cared.

*

I knocked on the house of a middle-aged white man who burst through the door. He said, “Is yours the candidate who said he wanted to create more opportunity for black males?”

“What do you mean?” I asked. The way he spoke showed his disproval of this idea.

“Last night at the debate, one of the candidates said he wanted to create more opportunity for black males. It did not go over well with the female candidates.”

I told him about the candidate’s desire to create equality for all schools and students, but I also told him about how the highest drop-out rates are among black boys. He may have been addressing this. The man held the flyer at eye-level against his brick wall, squinted at it, and told me he would consider my candidate. He remained undecided.

Later I stopped to admire a woman’s garden. A raised bed burst with foliage and food. On the side of her house, tomato plants dangled from hanging pots. In her yard, a sign supporting my candidate stood. The woman appeared in her fifties, tall, with grey hair, brown skin and freckles. She joked about the sign, as if I hadn’t seen it. She offered me water before I left.

*

I saw lizards, wasps, roaches. The glass covering of a porchlight contained a graveyard of moths. Four dogs basked in the sun of a house with an eviction notice. A woman told me the people had left them when they moved. In someone’s driveway, a cat meandered around a turtle with a spiked tail. No body of water, not even a culvert, was close.

*

I met my supervisor, a young woman who worked the rest of the year for a consulting firm in D.C., at an upscale, fairly-new Market in Mid City. The White Star Market has coffee shops that sell cold-brew, nitrogen drips. Gov’t Taco serves a single taco with coffee/chile rubbed beef, avocado crema, hot sauce, and pickled red onions and jalapenos for $3.50. Chow Yum Phat serves a ramen bowl with broth, seared pork belly, ajitama, woodear and shitake mushrooms, enoki, mayu and scallions for $12. When my supervisor said that these neighborhoods barely ever get canvassed, I told her that the main obstacle I was running into was the citizens’ wariness of a young white man in their neighborhoods asking them about voting.

As African-Americans make up the majority of the district, its citizens reluctantly trusted me – a white person walking into their southern neighborhoods to ask them who they planned on voting for. Often, I got, “I’m not going to tell you that.” “That’s my business.” “We don’t talk about that.” Even though the picture on the flier showed that the candidate I was canvassing for was black, these citizens were still aware of Republicans’ ongoing voter suppression efforts. Shortly after inauguration, Kris Kobach, appointed by the Trump Administration, headed a committee secretly aimed at creating data to justify oppressive voter ID laws. In North Carolina, Republican senators in the state legislature attempted to eliminate the final Saturday of early voting in state elections. Black voters routinely show up to the polls on this day. In Georgia, secretary of state Brian Kemp, running for Georgia Governor against Stacey Abrams (who would have been the first black governor in US history), used an exact-match signature system for absentee ballots. This system put the registration of 53,000 voters on hold. When Abraham recently conceded that her candidacy held no viable path to the governorship, she noted, correctly, that “democracy failed Georgia” and “eight years of systematic disenfranchisement, disinvestment, and incompetence had its desired effect on the electoral process in Georgia.” Similarly, in Randolph County, election officials attempted to close seven of the nine polling places. To justify these closures, the election officials stated that the polling places do not properly accommodate Americans with disabilities. Sixty percent of this county is black. In North Dakota, the states supreme court upheld a controversial bill which required a street address to be listed on state IDs. Many native peoples living on the reservations in North Dakota use only P.O. Boxes. The examples go on and on.

Voting is the foundation of our democracy, or our democratic republic, if you want to get technical. This is something your high-school civics teacher will tell you, and it’s true. Any attempt to disenfranchise Americans right to vote borders on treason. If you don’t understand this, you’re part of the problem. So, when people were skeptical to admit their voting intentions, I understood, and simply told them abut my candidate, answered any questions they had, and gave them a flier. I marked “No Response” in the app.

Near the end of a long day, a woman peeked through the blinds and asked me who I was and what I was doing at her home.

“My name is Jesse. I am canvassing for the upcoming schoolboard election, ma’am.”

“Who are you?”

I repeated myself. I asked if X was home.

She slightly cracked the door. “How did you get my name?”

When I told her that both parties have voter-registration data that helps them target supporters, she told me that she doesn’t like that her private information is open-access. I understood her concerns. I really did. The app that I used to find the addresses of potential voters also included the person’s name, age, telephone number, and political affiliation. Eventually she stepped outside and we talked not only about the candidates but also about the ability of political parties as well as corporations to mine and database American’s personal data. Somewhere, someone is getting paid to monitor and store records of your life – what websites you visit, what words you type into search engines, what you purchase and who you vote for. It’s terrifying.

At the next address, I spoke with a woman who leaned into the half-opened door. As I started to talk about my candidate and the state of our schools, the woman told me that everyone in her family attended private schools. Apparently, it was not her concern. I responded by telling her, in a way that felt almost cliché but is still true, that the public schools are the life of the community. They are a reflection of but also shape the values, economics, and crime-rates of an area. These students graduate or they don’t. They go to college or they don’t. They start businesses or they don’t. They get good jobs or they don’t. They buy houses right beside yours or they don’t. But first, they attend our schools.

I left the woman’s house. As it started to set, the sun abated the heat and allowed some of the sweat on the middle of my back to dry. When I rounded a corner, I saw a boy and two girls, probably in their early twenties, standing in the driveway, talking. The house was not on my list, but I talked with the boy about what happened next door. On the lot, the carcass of a house stood. Its brickwork, painted white, stacked upwards to a burnt-away roof. Half-scorched boards leaned into a grey carport. Parts of it were cindered and toppling over. I asked the boy if he saw the flames. I asked the boy if anyone lived there. I asked the boy if anyone died.

The owner was asleep inside its walls as it burned.

About Jesse DeLong

Jesse DeLong teaches Composition and Literature at Louisiana State University. Another essay can be found online at Sisyphus magazine. His poems have appeared in Colorado Review, Mid-American Review, American Letters and Commentary, Indiana Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Typo, as well as the anthologies Best New Poets 2011 and Feast: Poetry and Recipes for a Full Seating at Dinner. His chapbooks, Tearings, and Other Poems and Earthwards, were released by Curly Head Press.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)