You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Day something in lockdown. I was doing a play, I got ill, the play stopped, I watched The Godfather 3, I got more ill, I watched When Harry Met Sally, we ate bulk-bought long-life food, I couldn’t taste it, she couldn’t imagine that, she got ill, she couldn’t taste the food either, and that she couldn’t believe. A month or so later, the time flies by in packs of seven, a day ends as instantaneously as we welcome a new one, it’s gone fast but a lot’s happened.

Can I just put it out on the street? Is that legal?

My girlfriend is a Drama student, she’s a poor drama student, we both were (I’m not a student any more, but I was, and I was poor), but she still is, a drama student, and she’s still poor.

We live in a one-bedroom attic flat. It’s cheap, relatively close to her school and subsequently complete with all the accoutrements you’d expect from such a lavishly tailored residence: broken appliances, damp, and best of all, mice! Only an experienced master builder in the deepest depths of creative sleep could dream up a more idealistic utopia for us to coexist for weeks on end. But we press on.

She receives the email from school: “Classes will be taught remotely”. Time for an action plan. We divvy up the space and decide she will take the bedroom and I, the joint living room/kitchen area. It’s a fair deal and there are smiles all round.

I had a small purse saved from a recent theatre job, and they kindly agree to keep supporting the actors until what was meant to be the end of the run (this was before the Furlough announcement in Rishi Sunak’s Decalogue) – I was relieved.

I wonder If I can recycle it somewhere? There’s gotta be a microwave recycling place somewhere right?

Drama. Home. I know what you’re thinking, I was too. Drama? Remote learning? Just when you thought an educational body couldn’t be more naive about the class divide within its institution, they pull me back in.

I turn off the movie.

I suppress the internal fury and we do some remote interior location scouting.

“Yeah, I’m sure we could set this up to look like a train station? We can make this work!” – nine grand a year really being put to the test as I feign unquestioned positivity.

“Really? What about the wardrobe in the corner?”

“Well, we can move it over he— … oh it’s built in. Well how about this wall?”

“There’s more light over there.”

“Yes, but there’s less wardrobe over here.”

“This is so unfair, no one else has this problem, they all have bags of space, Tilly’s gone to the country with her mum and d—”

“Stop, stop – there’s no point comparing yourself to Tilly.” (There is. There’s always a point in that. Fuck Tilly.)

“It’s not fair, I can’t do it.”

“Okay… Okay, fine – so we’ll send an email saying we reject it as a form of training.”

“No – I can’t!”

“Why not? I can help you write it?”

“Because, then in third year … the casting in the plays it’s … I can’t. Look, it’s fine, it’s fine! I’m being silly, I’ll just do it, I’ll stop moaning and just do it, it’s fine. Thank you for helping, I love you.”

I should perhaps unpack some of the Chekhovian subtext here. Let us begin with a brief character backstory: every poor drama student faces unfair disadvantages throughout their training. Maybe that’s too vague, let us dig deeper and relate it directly to the extract above. In the scenario, our protagonist “Young student” wrestles with the feeling of wanting to complain, while weighing up the possible consequences of doing so. The fear of school faculty seeing her as “hard work”, “a complainer”, or “a difficult one” if she speaks out, subsequently informs her choice.

Once “Young student” has made her decision, she will then find herself in the familiar scenario of being further down the ladder, struggling and stressing to catch up, silently defying the multitude of class-based disadvantages, just to be level with her fellow privileged or “normal” students, who in this case, have an abundance of learning space in the country.

If I want to donate the microwave, do I have to get one of those green “TEST PASSED” stickers?

I retreat back to my assigned territory. My gym, my office, my six by nine. I am now a content lodger who quietly exists in her inadequate domicile theatre.

The sky is black and I still haven’t eaten. It’s probably too late to cook now. Suddenly I’m watching clips of the 2012 Olympic games – boxing, running, cycling.

I glance at my watch, the hour hand begins another lap – the smooth rider making his way around the metric velodrome cruising incessantly toward the number ten. He’s trained for this, I haven’t, I can’t fight it, I’m a pawn in his game of time. I sigh. Curtains down on yet another day. Oh well.

Starring off into the distance, my eyes float aimlessly for a while before landing on the empty space between the bottom of the door and the floorboards. A few minutes is all they need, some time away from the screen… I take in the muffled sound of an evening play-reading going on in the makeshift studio. I can’t make out the story or the words but it comforts me. I’ve slept in the wings before on a job and it takes me back, emulating those brief moments of respite in technical rehearsal where an actor simply gets to exist in their place of worship, curled up in a corner taking in the mantra of the experienced prophets treading the boards, I smile contentedly.

Still starring at the gap in the doorframe I take some deep breaths… In … out … in … out … in… mouse… Mouse? …oh shit, MOUSE!

Wielding a pole, I spring up onto an armchair where I stand – alert. The aerial view of the room giving me a false sense of advantage over the elusive rodent.

“What’s going on!?” she cries from the theatre, breaking character mid-play. Shocking. Paying audience, shocking.

“Shhh! It’s the mouse, babe! Stay in there!”

“WHAT!?”

“SHHHH I said it’s the mouse!”

I step from chair to sofa to cabinet.

I wade through furniture, clawing back each piece from the wall into the growing pile in the centre of my cell.

Only one piece left to move, nowhere left to hide, I prepare to strike – “Babe! I need your help!”

She runs to my aid, we talk through the movement, it has to be fluid – “We have to work together, needs to be like clockwork, one move, like a synchronised dive okay?”

“Okay.”

“Okay… On three, as you move, I strike – okay?”

“Yes, I understand yes!”

“Okay, let’s go.”

“What about the blood?”

“Never mind the blood, mice don’t have blood.”

“Really?”

“Well they probably do, but probably not enough to splat.”

“Eugh, I can’t deal with a splat right now, it’s too late to clean up a splat.”

“Babe, I don’t want a mouse in the bed.”

“Can they get in the bed!?”

“Of course they can get in the bed!” Another nine grand well spent.

“We have to kill it then, we can’t have it in the bed.”

“On three – one, two…”

It all happens so fast, the movement, so fast, the discussed routine executed to perfection – precise, so fast, brilliant.

But alas – no mouse.

So, there’s a place in Leyton that does microwave-recycling, actually does all appliances, quite expensive however, I have to pay, to give it to them. Well that’s not happening.

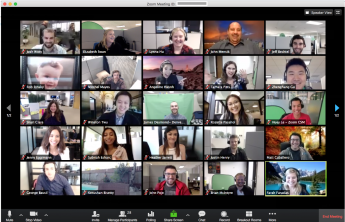

For the next two weeks, in our tiny mouse-ridden damp house, with inadequate space and noisy neighbours, I watch my girlfriend work against all the odds just to keep up with the class. With infectious positivity she smiles, she chats, she laughs, she carries on. She Zooms, she house-parties, she has classes on weekdays and works on her personal project at the weekend. She defies the odds and cooperates with the guidelines of an institution that didn’t think to consider how class and living situation might affect the practicality of what they were asking. She writes fantastic scenes, battles the elements to film them and manages to submit all her work before the deadline. Success!

INT. BEDROOM – SCHOOL ZOOM MEETING – MORNING

TEACHER

I think your living circumstances have affected the quality of your work.

“Did he really say that?”

“Yes.”

“Jesus.”

Do my mum and dad need a Microwave? No. Do her mum and dad need one? Maybe, actually.

As we begin to dip into the reserves of our optimism, the time has come to leave this house. Germs outside. Germs inside. Everything a germ, it seems. Can’t afford to live here any more. No help from the landlord. Despite hearing many tales of generosity whispered around town, it seems in our case their need for profit outweighs our need for charity. I can’t say I’m shocked, but I expected more. Times like these really do expose the core.

We are lucky enough to have some options. She can stay with her mum and dad, where I’m also welcome to reside – or I can head over to my parents. We can decide that later.

We’re going to have to throw a lot of our belongings in the bin – clothes, books, plays etc. They can’t come with us, there isn’t space. We make two piles. Keep – throw. It’s a relatively painless process, they’re just things. We have each other.

We start packing everything into boxes and plan the best way to move things out. Multiple trips over two weeks seems like the best option. Last thing to go will be the bed, roll it up in a tarpaulin, something like that.

Then that will be it.

We’ll be moved out.

Onto the next chapter.

It is around this point, as I peer into the seemingly empty storage cupboard checking for some forgotten relic, that my cumbersome friend takes centre stage to guilt me with his electromagnetic soliloquy.

“Why won’t he take me? Does thou know how well I work? To cook, to heat, to work – oh to still work and not be wanted! What curse is this to be capable of such spectacle that would have convinced the pilgrims of divinity and yet to be worth nothing? For one’s wizardry to become drab.”

Ignoring his cries, I shimmy him out and onto the floor. Bending down I scoop him up into my arms, his fate sealed, and we begin the long decent to the ground floor. There is a bus stop adjacent to our house, that’s where I’ll leave him – the least I can do is provide some shelter on these unforgiving streets if only to elongate his chances of being adopted by someone in need.

“Didn’t your brother buy you that microwave?”

“Erm… Yes. Yes, he did.”

“And you’re throwing it away?”

“Yes?”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes?”

“You don’t sound sure, oh… Coming!”

The virtual call of some fellow player ends our exchange.

But now, I have my brother in my arms. Stood on the stairs, it’s my brother in my arms, on the street beneath the bus shelter, my only brother sat in the cold spiky rain. He’s only small, we can take him with us, can’t we?

About Alexander Harvey Moffat

Alexander is a twenty six year old Writer, Director and Actor from Camden, London. His prose writing is often autobiographical with themes including class, relationships, creativity and mental health.