You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

To be young was very heaven! Wordsworth

Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me, as is ever so on the road. Jack Kerouac

From boarding school I hitch hiked to the Rolling Stones’ Hyde Park concert, summer of 69, hoping to catch a support act, King Crimson. There were up to half a million people at the famous free event, but when a friend and I arrived it was empty. We were a week early, spent a miserable night avoiding park patrols under bushes, freezing in T shirts, then had to hitch back before our absence was discovered. Bear in mind I was only 14, and that this was an age before emails, mobile phones or the internet. Communications then were by expensive landline or print, more Victorian than 20th century.

I was captive in a school run by monks deep in the English countryside for most of the year. In the holidays I hitched to parties, music festivals and concerts (and caught up with King Crimson at Hyde Park in 71), but what promised a tantalising world of further adventures was a semi autographical novel by Jack Kerouac. I read On the Road after that first mistimed hitching effort and it changed my life. I was an avid reader then, had read many of the ‘great works of literature’, but Kerouac was new. He riffed about hopping freight cars, getting lifts, skirmishes with the law and adventures. His lifestyle was assisted by the Federal Government offering 90% of the funding to build the vast Interstate Highway System in the 1950s.

Kerouac seemed a ‘bennie’ fuelled descendant of the poet Walt who described himself as, ‘Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos . . .’ Keeping one step ahead of whatever was left behind seemed to be the point of travelling for Kerouac. He wrote: ‘A tall, lanky fellow in a gallon hat stopped his car on the wrong side of the road and came over to us; he looked like a sheriff. We prepared our stories secretly. He took his time coming over. “You boys going to get somewhere, or just going?” We didn’t understand his question, and it was a damned good question.’

Travelling is old hat. Five centuries after Herodotus, Romans were enjoying their own Grand Tour, but the art of hitching a ride began in the automotive continent of North America. By 1927, the New York Times was declaring: ‘The season proper for ‘hitch-hiking, now an established mode of travel, ends in September.’ By 1930, one in 5 Americans owned a new or second-hand car, and though the Great Depression of the 30s slowed ownership, it was still much higher than in Europe. You can see Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert sitting on a fence glumly hitching with their thumbs in Frank Capra’s 1934 screwball comedy ‘It Happened One Night’.

The seventies found me studying at Keele University in the Midlands, an educational establishment with one great advantage (apart from an amazing contemporary music series and a Marxist sociology professor who didn’t believe in exams) it was in walking distance to a Motorway Services. They were great hitching points as pedestrians are not allowed on motorways. I remember arriving at the off ramp to London one Friday and counting 24 people hitching, alone or in pairs, many holding handmade signs on cardboard with their desired destination. I knew it wouldn’t take long to get a ride, even as a long-haired specimen of the male gender.

We would take off on long summer holidays, hitch a lift from cars boarding the ferry at Dover and then away east or south, the days unfolding as unique and unknowable. I had no responsibilities I knew of. Tomorrow was holding its breath and the enormous present seemed barely digestible.

The art of hitching requires concentration, any car or truck can stop (a Roller did once) so I would try to focus on each one and consider where to stand, where the driver could clearly see me and stop safely. It’s common sense, but still requires experience. Occasionally, I’d ask drivers at rest stops and petrol stations, but that was very rare; I always felt uncomfortable.

Sticking your thumb out is an invitation for conversation and applies no pressure, apart from fleeting guilt by a few motorists passing you in the rain. Just the fact one could stand by the side of a road anywhere and meet strangers who offered temporary hospitality and with whom one exchanged conversation and opinions describes a society very different from today. There is generosity from the driver sharing their material goods and time (sometimes we would be dropped off out of the driver’s way or occasionally given a meal or bed for the night). The passenger, ideally, entertains by opening themselves to others. There’s the suggestion and usually an offer of, but no demand for, reciprocity, not in an economic form, but in a fleeting friendship co-created. Strangers are relatively recent, a feature of cities, but our daily urban encounters with people we don’t know, lack the intimacy of sitting next to someone in a tight enclosed space.

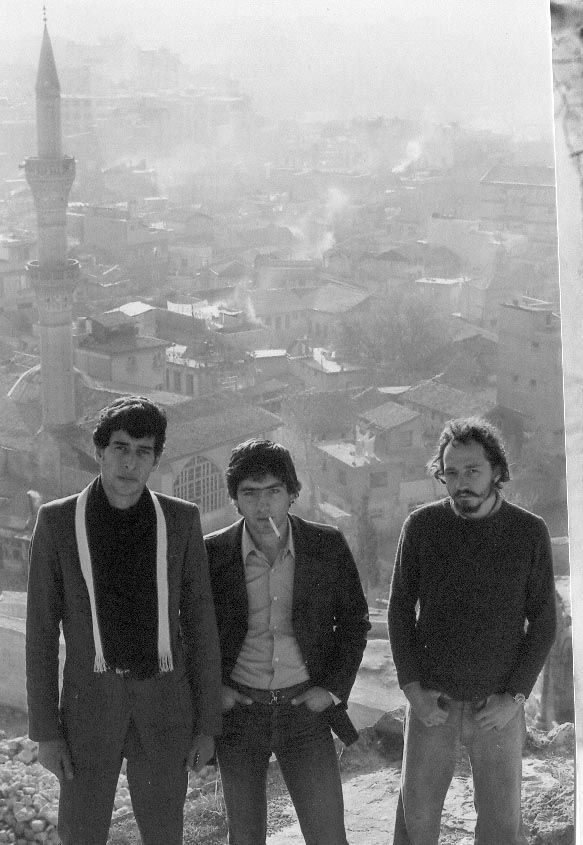

I am a fair conversationalist and so hitchhiking was never a problem, even with no common language. The best hitchhiking countries were New Zealand and Turkey where a smile and a couple of phrases roughly pronounced (güzel, teşekkür ederim) always went a long way.

My gestural technique was to sweep my right arm forward in an exaggerated fluid motion with thumb pointing in the direction of travel then revolving anti-clockwise almost 180 degrees. The first time I hitchhiked in Iran was just past the border post. We stood there expressing the art of the thumb and curious drivers stopped wanting to know what we were doing. I explained that the magic thumb meant we wanted a lift for free. In the mid-seventies private cars were uncommon there and would often give people lifts for some financial reward. But we were firm. It was our way of riding trajectories far and wide, making journeys on next to nothing. We lived on bread, cheese and tomatoes and camped nearly everywhere, even in cities.

The flâneur is the casual, wandering observer of city life, but we found walking much too slow. We spent more time in ruins than the aspiring towers, spires and minarets of the city, having little money or interest in consumables. I remember being dropped off late in a large city, exhausted we camped at sleep’s command on the first patch of grass, woke on a roundabout with the rush hour roar spinning around us. We peered through the tent flaps at men in suits swallowing another day at work. We lived in the now, in the chewy world of haecceity, hearing new languages, smelling strange smells, eating strange foods and adjusting to strange customs. Then there were the ruins, palaces and sublime landscapes that most tourists enjoy. It was fun, exhilarating, hard work and often uncomfortable, but we had a feeling that luxury would render the experience inauthentic – non-local and lacking diversity and difference.

A few lifts my memory has chosen:

Most memorable

The sandstone palace of Amber was impressive with its labyrinth of gardens, courtyards, temples and wonderful colonnaded audience hall with elephants trampling the columns. An army of extras with elephants and camels decorated in technicolour extravagance were heaving below the ramparts. Filming finished late in the afternoon and the multi-coloured menagerie started trailing back to Jaipur. As a laugh, I held out my thumb and a mahout smiled, stopped and lowered his elephant. We climbed aboard the beautifully decorated animal, the gift of colour painting its ears and rich cloths cloaked across its back. We joined the parade, our driver astride the animal’s neck left sunset to us, a magical ride passing temples and palaces rising out of the waters of the sacred lotus gilded by the blade of the sun.

Hottest

We squeezed into the cabin of an old English Bedford or Leyland lorry that slowly rocked and rolled north. The engine was hammering below the gear stick, my right leg burnt each time it brushed the metal cowling and the pace was so slow we could have walked. The cabin was an insulated furnace so I simply gave up and asked to be let out half way between Isfahan and Shiraz. He refused at first, too generous, worried for us left in the desert with little traffic. We persuaded him to drop us off at some dusty crossroads. He was puzzled, but waved goodbye. Suddenly burdened by delicious silence we were nudged by the faintest breeze, as if from heaven.

Coldest

In the Zagros Mountains near Kermanshah, we grabbed a twilight lift, chucked the packs in the trailer and stood on the connecting frame, holding on tight to the tractor. When we stopped I found my fingers had glued to the metal. I had to blow and spit to free them then pitch the tent in conditions simulating a polar winter.

Longest

The field behind was littered with used condoms (don’t ask). Planes roared overhead and trains rumbled behind us, as we stood beside the glittering procession motoring from Naples to Rome. After half a day of noise, and bored, I flashed my legs in the Cancan, but that didn’t seem to work.

We found a handbag in some bushes, full of feminine clutter but no purse. We tried flagging down Carabiniere but they just sailed past. We spent the night in that disgusting field, replacing the bag, not wanting it found in our tent. When we woke the bag was gone. Eventually a Vdub campervan stopped, bringing a slight disappointment that we hadn’t broken the 24 hour barrier (which I broke two years later beside a derelict church near Burgos, Northern Spain). The only memory my mate retrieves from that day is, ‘We were going a bit weird with flickering anticipation and failure every few seconds.’ Memory fictionalises the past, but I remember piling in the back and discovering three young willowy apparitions, blonds from California. Their mother, a beauty herself, explained her mission which wasn’t to find suitable itinerant males to impregnate her daughters, but to follow the footsteps of St Paul.

Fastest

The sports car stopped outside Bristol and the middle aged man wearing a plausible cap leant across and through the open window asked, ‘Will you suck me?’ And was gone.

Fastest

A new Mercedes sprinting down the autobahn at over 200. The ingenious details flashing out of sight.

Slowest

For my second cross-channel adventure, we had booked a flight back from Istanbul, not yet confident how long hitchhiking home would take. We missed the flight. Broke, we stayed in a laminated fleapit hitching to the airport every morning to check availability. On the second or third day we made do with a donkey and cart, from the ancient to the modern. Our luck then changed and my welcome home was made special by a customs officer who stripped me and undertook a thorough search. As his latex fingers parted my cheeks I mentioned that I hadn’t washed for over a week and suffered aerobic bouts of explosive diarrhoea. I’ll never forget his simple reply, ‘Just doing my job sir.’ And my response, ‘It’s a friendly warning, that’s all.’

Longest

Somewhere south of Belgrade an English truck driver stopped for me. We just missed a truck jack-knifing across the highway in heavy rain near Skopje, but reached Tehran, over 3,000 kilometres east. It turned out that he lived in the street in Camberley where I took my first steps. On the road, coincidences are commonplace, though we had nothing in common.

Coolest

We were hitching across southern Morocco, the border being closed, when two German couples in a Vdub campervan picked us up. We lay in the back with Can’s Future Days blasting out of their modified sound system, hallucinating mirages bleeding into the dunes, occasional ruins at sea in waves of sand washing up against mountainous backdrops. The sky bloated blue on empty, the music squeezing every inch of consciousness, stoned.

Most boring

A three day visa had to see us through Bulgaria, then tucked away behind the Iron Curtain. Two long haired youths got plenty of stares from drivers, but they were suspicious, few stopped. Only one ride has stuck. A young couple squeezed us into something like a Trabant and took us back to their tiny flat in an anonymous row of high-rise apartment blocks drained of colour on the outskirts of Sofia. It was Saturday night and prime time viewing on their small black and white TV was a tractor factory tour, but they were lovely and with no language in common.

Warmest

A young white couple picked us up hitching down the mountains from Inyanga near the Mozambique border. They were from Zambia and on their honeymoon. I expressed surprise, confessing I’d never pick anyone up on my honeymoon, if I ever had one. They were lovely, shared a wedding present, finest quality biltong, and wanted us to spend more time with them. The kindness of strangers . . .

Richest

A youngish guy gave us a ride in a most comfortable luxury car. He had made his millions selling new-age musac and was on a high. Later that day, his first satellite was being launched from French Guiana providing 82 TV channels. I thought it a strange idea and asked where on earth you could find the material for all those channels. He said some would be time shifting, others would find new opportunities. He saw a future I couldn’t imagine from Seattle. I now have about 150.

Most celebratory

A Glaswegian picked us up hitching out of Bulawayo and despite being in Africa for over 40 years, he was as hard to understand as being accosted on a Saturday night in Sauchiehall Street. He managed a gold mine and as we arrived late afternoon a shift was ending. Tired miners shining black beneath their tin hats were emerging from the ground. His ‘house boy’ beat our dirty clothes to death in the bath while we sat on the stoop with a drink gazing at the camp fires littering the valley beautifully. He put on the BBC World Service news and after the pips they announced, Mandela has been released. We were ecstatic; the State of Emergency across the border was over. We danced a jig or two and drank well into the night that twinkled with stars and all those camp fires seeding light.

Wild

Somewhere east of Belgrade, two German guys, about ten years older, picked us up in a vintage black Mercedes. They were tearing through the countryside on a mission to find bars. We stopped in villages for a drink where I would practice my Serbo-Croatian (now a politically charged term). It was our first time hitching abroad and at the very last minute had purchased ‘Teach Yourself Serbo-Croat’ from Foyles ‘the largest bookshop in the world’, discovering later that it was a reprint from 1941. So my handy phrases included, ‘My father is a submarine captain’, ‘My sister is a nurse’, and, ‘I was wounded in battle’. We made no sense, and being drunk even less.

Mostly forgotten

We were stuck in Morocco, a country giving us plenty of hassles. The borders south and east to Algeria were closed so we headed to the Rif Mountains, Berber country. We were picked up by a farmer with two old smugglers in tow, Ronnie and Lonnie, a Kiwi and an Ozzie who said it wasn’t safe hitching there. The brand new Mercedes delivered us to an old stone cottage where his wife cooked for us on a fire. He said he had a brand new flat in Rabat and intimated a new girlfriend. The common green hashish of high quality was called Zero Zero, but this farmer called his Sputnik, ‘because it puts you into outer space’. The experience was trippy and craft based. We learnt to make carrot and potato chillums, swam in the river, drifted along the terraced hillsides and lost a week high in the marvellous mountains.

Weirdest

Four of us squeezed into the cabin careering through the Zagros Mountains. Stopped for a pipe. ducking through a low threshold onto tattered carpets, old men were seated along the walls, a chai boy appeared then the pipe and I was tutored in long drags. Back on board the horizon wavered with endless mountains and wild bends, wide eyed constellations, countless miracles in the richest blackest velvetiest night. If it was good enough for Keats and Coleridge . . . another mountain stop, more pipe, back on the road still climbing, the boy clambers out of the window with the truck bouncing around and brings back a watermelon, red flesh gash juicy logic of gentle easy dreams. The driver was a lovely guy who badly wanted me. I have a key, he kept saying, as if privacy was my only concern. I really liked him, kissed him goodbye, lost in Persian happiness.

Most careful

Bouncing around in the back of the jeep we stopped on the outskirts of Qom, Iran’s holy Shia city. The soldiers told us to cover our shoulders and drove us to a shrine, giving us scarves to cover our hair and faces, and telling us not to speak if spoken to. We packed into the scrum edging forward towards the brightness of the shrine. Impassioned women were rubbing the gilded grill and stuffing banknotes through the bars. The dazzling light attracted prayer, the golden tomb as bright as glass was numinous with mysterious excess.

Most illegal

Under a blanket on his back seat, the US Airman smuggled us into the United States of America in Italy. Everything came from back home: the news, the milk, even the dope. The guys said the only local goods were prostitutes. We spun out, ate too many pancakes out of a bottle, drank too much out of a bottle, and discovered the wonders of peanut jelly sandwiches with the munchies. We collapsed in the bar, watched a basketball game and drooled at the price of hi-fi in a store. We had the run of the place. This was before the infection of terrorists targeting civilians, before security checks at airports, before the world’s first plane bomb.

So what changed?

For the twentieth century tourist, the world has become one large department store of countrysides and cities. Wolfgang Schivelbusch

There are many lost arts and while the lost wax casting technique is not one of them, adventurous hitchhiking is, which for me was the story of the seventies. That decade is a bit of a joke now, the hair, the fashions that ranged from platform shoes and hotpants to bellbottom jeans which advertised freedom and optimism. That was torn to black punk regalia or bright disco jump suits towards the end of the decade with a severe economic recession and growing unemployment.

You rarely see hitchhikers these days. Hitchhiking went out of fashion for all these reasons and more:

• many more motorways with harder access points for pedestrians;

• a richer world where many young people own a car;

• cheap cars are now much more reliable;

• cars now have radios, music systems and mobile phones to keep drivers occupied;

• it’s also a faster world where young people are not interested in spending hours waiting by the roadside; and

• then there were the murders. Though, statistics show that hitchhiking is not a particularly dangerous pursuit.

A youthful saga of long trips ran with spontaneity, intensity, yearning, frustration, silence, annoyance and sometimes danger. Thumbing through my mental library of lifts, 99% are extinct, but many of those led to adventures which are now experienced as part of ‘a gap year’, a rite of passage for young westerners.

Arnold van Gennep’s cross-cultural research (The Rites of Passage, 1909) uncovered three phases of boys becoming men: separation, transition (liminal) and incorporation. The decade of my main hitchhiking activity could be seen as the liminal period -‘removal of previously taken-for-granted forms and limits.’ Or I could just quote Pico Iyer, ‘We travel, initially, to lose ourselves; and we travel, next, to find ourselves.’ Unlike traditional rites of liminality, road trips never follow ‘a strictly prescribed sequence, where everybody knows what to do and how’ nor bow ‘under the authority of a master of ceremonies.’ We were on our own. The social nature of community, solidarity and maturation had changed.

That decade for me was the threshold (līmen means threshold) to emerge slowly as part of a community in work and play. Hitching was never a pilgrimage because there was no sacred or miraculous connections with any of the amazing sites I visited, Mycenae, Persepolis, Great Zimbabwe, Karnak, Tulum and many many more.

My brief descriptions of notable lifts may sound like I was continually off my head. I wasn’t. It’s just that memorable stories often seem to be associated with Dionysius. John Urry in The Tourist Gaze, points out that travellers and tourists desire novelty, ‘potential objects of the tourist gaze must be different in some way or other. They must be out of the ordinary.’ They should stream, not hang around, new experiences and new sights are demanded by tourists. Does speed necessarily mean shallow? Can being on the road achieve any depth of understanding? Well, not compared to an ethnographer spending years studying a remote tribe, but I felt my brief acquaintances were important – and sometimes led (long before the age of Facebook) to years of letter writing that would taper off eventually. Dean MacCannell argues that sightseeing is ‘a way of attempting to overcome the discontinuity of modernity.’ He thinks that tourists/travellers seek faraway places to gain a sense of identity from gaining a sense of authenticity and reality, which I think has some truth to it.

Travel experiences have changed, tourist sites are packed, even Venice in February. Tourism is now the largest industry in the world, employing vast numbers of people. Last year over a billion tourists abandoned the shelter of home for a time. This tidal wave reaches everywhere, even Antarctica, and effects every place it reaches. Some it engulfs, the people, ecosystems and landscapes, particularly coastal ones. Tourism is culturally very destructive, but has raised standards of living. I read that package tourists spend 80% of time in or around the hotel. We travelled to experience other cultures as they were and were blissfully ignorant of our privileged position, or that the poverty we often encountered (and often experienced transiently) could be otherwise.

Young travellers have credit cards and mobiles, connect up more often with each other than the locals. For most, partying is prime motive and the exploration of foreign cultures minimal. It’s less the spirit of adventure than spirits, Jägerbombs and such like, with the Lonely Planet to hand. We had no guide books and so gained the excitement of the new and unexpected and missed out on much understanding as well as sites of interest. My nostalgia is common and is not new, yearning for earlier travelling ways is historic from African explorers, to taking the Grand Tour, to getting places by tramp steamer.

Not everyone feels this way. The travel writer Pico Iyer says, ‘Taking planes seems as natural to me as picking up the phone or going to school; I fold up myself and carry it around as if it were an overnight bag.’ And a colleague’s twenty two year old son emailed me a few years ago after a brief chat about travel. I’m not sure what I said to rile him, perhaps by contrasting ‘tourist’ and ‘traveller’. He wrote: ‘when I go to india it will be to meet my peers, not to chase some romantic ideal of what it is to shed the free education, affordable housing, and massive consumer demographic and pop culture that i was born into bah stupid baby boomers. I wasn’t born into that kind of easy middle class affluence, not do I live it now, so I don’t see the romance in shedding it.’ He had a point, but so do I.

We had no great ambitions, to cross Africa, or find the source of the Amazon, we were just being ourselves, reigning with youthful exuberance. The following supposition by Alain de Botton didn’t apply: ‘In the gap between who we wish one day to be and who we are at present, must come pain, anxiety, envy and humiliation.’ That youth is now in shadow. I turned 60 this year and presume that my hitching days are over. Home has been viewed as negative, in thrall to ruling ideologies, but I love my home and getting to know the place where I have settled, beside a forest by the sea. In fact I worry about travel, not only for its homogenising effect on cultural and language diversity, or the carbon cost of flying, but the effects on those who travel. There is more than enough arriving and departing, appearing and disappearing, saying helloes and goodbyes.

Place is key to understanding where we fit sustainably in the environment, and a sense of place is only fully achieved by paying attention to staying put. I live in Gumbaynggirr country and appreciate the Aboriginal way of being, of understanding landscape, history and ecology, and their style of reciprocity. And this alone shows how unsustainable the art of hitchhiking is on the personal level of creating a home, discovering place and becoming part of a community. As Blaise Pascal unreasonably said, ‘All men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.’ (1654).

I can’t recall the first lift I ever achieved, but the last one was from two young Chinese vacuum cleaner salesmen in Sarawak, which I thought funny as most of the houses we’d seen had earth floors. And that reminds me of a most fortuitous lift in that country (on the island of Borneo) about a decade earlier. I was lost in the jungle, so followed a stream down to a small river, and after a nervous few hours waiting managed to hitch a ride from a passing boat. The world keeps changing as we do. I don’t see hitchhikers here on the coast, but have given lifts to hippies still living Nimbin, Mullumbimby way, because I remember with gratitude all the thousands of people who showed me kindness on the road.

Like all great travellers, I have seen more than I remember, and remember more than I have seen. Benjamin Disraeli.

About John Bennett

After finishing university in England I travelled widely and ended up in Australia. I worked for National Parks & Wildlife among other organisations, gained a PhD and taught at university. I am a poet, photographer and essayist.

Thanks for the insights, John. As a late ‘explorer’ of my country side by motor bike I can relate to this passage:

Arnold van Gennep’s cross-cultural research (The Rites of Passage, 1909) uncovered three phases of boys becoming men: separation, transition (liminal) and incorporation. The decade of my main hitchhiking activity could be seen as the liminal period -‘removal of previously taken-for-granted forms and limits.’ Or I could just quote Pico Iyer, ‘We travel, initially, to lose ourselves; and we travel, next, to find ourselves.’ Unlike traditional rites of liminality, road trips never follow ‘a strictly prescribed sequence, where everybody knows what to do and how’ nor bow ‘under the authority of a master of ceremonies.’ We were on our own. The social nature of community, solidarity and maturation had changed.

I find a serene peace on the road, a freedom without responsibility, an unknown destination, followed by the pleasure of the return to my loved ones..