You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping H is for . . . Happiness? Except when it’s not. Hugs, hurt and heart . . . some of these I know better than others, as does Emma Bovary. To say that Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary shaped my life is a bold statement, but mostly true. It also re-introduced me to the loves of my life. At the risk of a double spoiler though, don’t mistake what follows as a confession to a string of affairs. It’s more a case of stalking.

H is for . . . Happiness? Except when it’s not. Hugs, hurt and heart . . . some of these I know better than others, as does Emma Bovary. To say that Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary shaped my life is a bold statement, but mostly true. It also re-introduced me to the loves of my life. At the risk of a double spoiler though, don’t mistake what follows as a confession to a string of affairs. It’s more a case of stalking.

Wind time back to my French A levels in the early nineties, and this 19th century novel was a set text. Two years later I headed off to Trinity College, Oxford, to find the book was also going to feature in my modern languages degree. By a twist of circumstance or fate (yes, one of the themes in Madame Bovary), I ended up living in Rouen for my year abroad – the nearest city to the novel’s main character Emma Bovary, and where part of its crucial action unfolds. By the time I finally emerged as an Oxford graduate in 1997, I’d memorised whole sections of the book. I then completely blanked them and the whole stress of my finals from my mind. Or so I thought.

Fast forward 20 years, and Madame Bovary was back on my doorstep. By that time, I was a published poet and mother of two boys. I was also suffering from severe depression and suddenly able to appreciate Emma’s story in a whole different light.

At first glance, it may be hard to imagine how a novel written in 1856 and set 150 years ago in provincial France could possibly shape a 21st century woman’s life in England, America, or anywhere in this now high-tech world. Reduce the story to its very basic strapline: ‘bored housewife seeks extra-marital excitement’ though, and Emma’s almost a character from Desperate Housewives, Sex and the City or a whole host of other contemporary series that I’ve already forgotten. (Or, alternatively, the intro for an ad/blurb/profile on The Ashley Madison Dating Agency.[1])

Except, of course, the storyline isn’t actually as simple as that alone (any more than my screen comparisons are). If I had to sum it up in only one sentence, it could also be the heartbreak and trauma of a character living beyond her means in order to escape the banality and emptiness of a provincial lifestyle, a spoiled and selfish adulteress makes her family’s life hell before taking arsenic or . . . It’s a book in three parts and several hundred pages long, so a concise summary is both impossible, and pointless. What makes the novel timeless in a way that the TV series aren’t for me is the mixture of great human characterization, wide insights and beautiful, crafted writing. All of these lie in the details, and Flaubert’s careful, precise attention to them.

Happiness is something I spent years chasing after. I would be happy with top grades, meeting the man of my dreams, my perfect career as a journalist, my first published book . . . Emma’s disenchantments are not dissimilar: ‘Before she married, she had believed herself to be in love. But, as the happiness that love should have brought did not come, she must, she thought, have been mistaken.’

If marriage doesn’t bring Emma all she wants, nor does religion, keeping a beautiful home or being mother to her daughter Berthe. Everything she believes is happiness soon turns out to be disappointment. She distracts herself instead with love affairs and buying material goods. But, along the way, she gets into debt and is preyed upon by conmen. Although this isn’t mirrored by my own life, what privileged western woman hasn’t been tempted by skin products promising rejuvenation, instant-thinness food options or the allure of happiness seemingly offered by that holiday brochure or pamper day?

Meanwhile, the changing emotions and non-communication that only exacerbates the difficulties in Emma’s marriage to Charles still play out similarly in countless relationships:

‘Perhaps she would have hoped to confide these things to someone. But how to speak of an indefinable unease, which changes appearance as the clouds change, which swirls like the wind? She did not have the words for it, the opportunity, the courage. If Charles had wanted it, however, if he had suspected, if he had once seen into her thoughts, it seemed to her that such abundance would have been released from her heart as the harvest of apples that falls from an espalier tree when it is shaken. But as the intimacy of their life increased, the detachment grew in her mind, taking her further away from him.’

Likewise : ‘We shouldn’t touch our idols: the gilt stays on our hands.’ This could be just as much a summing up of the media’s celebrity headlines as Emma’s lover Léon.

Another target of Flaubert’s scrutiny is medical science, pseudo-medicine and self-advancers – topics still relevant today with the rich-poor divide, Big Pharma, loan companies and financial services. While capitalism gets louder, truths become harder to discern from glossy techno babble and the false personal facades of social media networks.

Given the time period, Emma Bovary isn’t diagnosed even by her GP husband Charles, but there are clear hints of potential (manic) depression, as she alternates between sudden energetic moods and a kind of lethargic ill health: ‘On some days, she would chatter with a feverish excess; these exalted moods would be suddenly followed by periods of inertia when she didn’t speak or move.’

My own depressions have never been definitely categorised. But in 2013, I felt so low that I was passively, if not actively, suicidal. I couldn’t find a point in life and directly identified with Emma’s conflicting desire in: ‘She wished both to die, and to live in Paris’. For me, instead of Paris, simply substitute any fantasy, peaceful sunny escape location, or purposeful goal.

I was luckier than Emma in being able to talk about this and go to London for some pioneering repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) treatment. For five days a week, over four weeks, short sequences of brief magnetic pulses were targeted at part of my brain. As I had to live away from home during this, I took Emma Bovary with me.

Using Emma’s storyline as a basic fictional narrative framework, I kept a poetry diary of my treatment, which I then turned into a contemporary English poetry version of her story. The Magnetic Diaries was later published as a multimedia poetry collection and became a touring poetry-play.[2] I had massive support from friends and family, but it was this project which gave me the focus I needed to get through that desperate and lonely time in my life. In a sense, the novel went beyond shaping my life to saving it.

I’ve written more on The Magnetic Diaries and the rTMS treatment in my Wellcome Collection article ‘Creative energy: how electromagnetic therapy inspired me’, so I won’t dwell on that here.[3] Instead, I want to return to how Madame Bovary changed my life, rather than near-death.

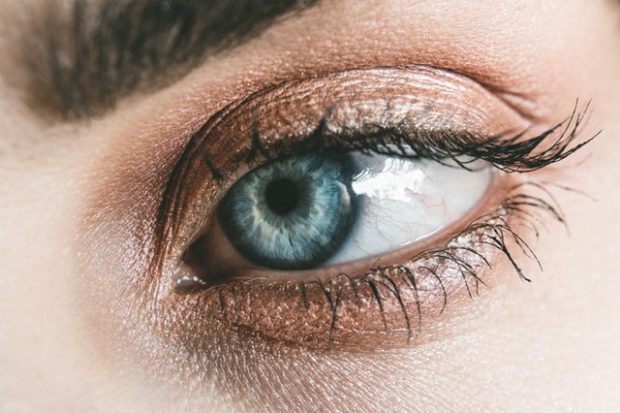

Hindsight and memory alter everything, but I think the stalking may have started with my addiction to Emma’s eyes. By now, I’ll probably admit too that I may be stalking Emma as much as she’s stalking me. My thing about Emma’s eyes is centred around Flaubert’s apparent carelessness over their colour. Are they black, brown or blue? Given the novel’s overall realistic exactness and close microscopic detail, it’s an imprecision that stands out. If it is a slip of Flaubert’s pen or memory, then it’s a lack of foresight that’s lead to much debate. But it could just as well be a stroke of genius – a tiny mystery that draws readers and critics back to re-reading in order to understand. For me, it’s certainly thought-provoking and haunting, at a conscious and subconscious level.

If I stare at my eyes in the mirror, sometimes they’re dark brown. Other times they’re hazelnut watered down. They’ve tinges of green too, in different light. Looking into my own eyes, I can also see my mirror-self reflected in my eyes in the glass. Me looking back at me looking back at me, looking . . . This is more than pure narcissism; I’m staring myself in the eye more times than I have real eyes. In that gaze, an infinity of shades, an infinity of reflections.

It’s all in the lens applied: mine, Flaubert’s, Emma’s . . . The shifting colours and tones in her iris might be seen as mirroring her mood. But Emma’s outlook also flows from the colours through and with which she views and tints the world, unable to maintain a steady perspective. The same could certainly be said of me. But would I have discovered this if I hadn’t been trying to make sense of Flaubert’s world as well as the world directly around me?

As for love and happiness, well, it’s probably obvious by now that I’m completely head over the heels with the novel. But the story doesn’t end there; it has also impacted on my other loves. I’m going to trying not to over-dramatise here – yes, yet another of Emma’s (and my) tendencies – but Emma’s miseries reminded me how much worse things could be. It made me realise how much I loved my children and wanted to be there for them, no matter how hard life felt at times. Also, that real love, partnership and marriage isn’t about the happy bits so much as sharing and dealing with the hard bits – like my depression – together. The hugs from my husband and children have never felt so warm or important as they did when I came home from my rTMS treatment.

My depression still isn’t cured, but I’ve learned to live with it. The same is true with my adulation of Madame Bovary. And yet still, as so often with love, I haven’t quite pinned down the exact characteristics – or character – I’m really in love with. It’s definitely not Emma’s husband Charles: ‘Charles’ conversation was as flat as a pavement.’ Ouch!

It’s not Rodolphe: a selfish, manipulative player who finds real emotion demanding and boring. Or weak and conventional dreamer Léon. They’re both more in love with themselves than Emma. Though the same might be said of her too, she is at least brave-hearted, or foolish, enough to live her emotions fully, however misguided they may be.

Is my real love then Emma herself? Yes, in a ‘Oh my God, really, hon?!’ friends’ kind of way. Of course, I’m also in love with Flaubert – the writer, that is, not the man. His prose has the concision, intensity, musicality, pace and beauty of poetry – a deal-clincher when it comes to charming a poet.

Despite all this though, my love is also part-narcissistic; the biggest attraction being that I’m more like Emma than I’d like to admit. I may not make the same choices, but I certainly recognise her feelings, including the boredom with mundanities, the need for hope and the search for something fulfilling. Flaubert himself is reported to have once said ‘Madame Bovary c’est moi’. Although unlike Emma, I have realised that happiness and fulfilment come from inside rather than external circumstances, and in self-love rather than self-adulation.

Although I’m not engaged in adultery with a man, I am having an ongoing love-affair with this novel. Madame Bovary may be a thing of fiction, but look closely enough at Emma’s feelings for the men, ideas, lifestyle and material possessions that she falls for, and really she’s only in love with her idealised version of them. When reality bites, each illusion falls apart. I guess I’m only hoping that the latter isn’t taken as read when it comes to the novel’s full shaping effect on the rest of my life. Otherwise, as loves on the side go, Madame Bovary actually feels like a sensible and healthy option.

About Sarah James

Sarah James is an award-winning journalist, fiction writer and poet, currently longlisted for the New Welsh Writing Awards 2018: Aberystwyth University Prize for an Essay Collection. Author of six poetry titles, a touring poetry-play and two novellas, she has been published by the Guardian, Financial Times, on buses, poetry trails and in the Blackpool Illuminations. She has also written for the Wellcome Collection website and a memoir was longlisted in the New Welsh Writing Awards 2017. 'The Magnetic Diaries' (Knives Forks And Spoons Press, 2015) was highly commended in the Forward Prizes. The poetry-play version was toured by Reaction Theatre Makers and a 'Highly Recommended Show’ at Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2016. She runs V. Press poetry and flash fiction imprint in the U.K.

It is really impressive article, If you are waiting to get the process to sync setting in windows 10 operating system then here you will learn to use the microsoft account to synchronize settings in easy steps.