You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Recently, my sister texted me a photo she had taken on a train in Singapore.

“Do you think that’s Beth?” she wrote. I held my breath and waited for the image to load on my cell phone. The last time I saw Beth was at the airport ten years ago when we sent her back to the Philippines. Her face, showing signs of ageing, was streaked with tears as she waved goodbye from behind the departure gates. I squinted at my cell phone screen. The woman in the photo had the same thick black hair, olive skin, and wide smile. For a moment, hope rose. Then it fluttered away. The woman’s proportions were slightly off – the forehead was too high, the nose too long, and, most of all, she looked too young. I texted my sister, “No, that’s not her.”

Elizabeth was the maid my parents had hired to live with us when I was three. She had introduced herself as “Beth” for short, but because of her accent, it came out as “Bird,” so that was what we called her since. She was twenty-seven, only a couple of years younger than my mother. She took care of my sister and me while my parents were at work. Picking me up from school. Cooking my favourite foods like fried chicken and fried eggplant dipped in dark soy sauce. Once, she had to cajole the five-year-old me for half an hour in the shower because I couldn’t stop crying after seeing earthworms that rainy day, afraid that they had found their way into the bathroom. At night, she would hold my hand whenever I was too frightened to sleep after watching The Swamp Thing on television.

“Bird! Bird!” I would call out to her in the dark. “I’m scared.” Beth slept on a floor mattress next to my bed. Sometimes, it took a few tries before she woke up. She knew what I needed without asking and, with a grunt, would throw her hand up like a life buoy. And just like that, I felt comforted.

Unlike many other maids, Beth spoke English well and was literate. She read romance novels before sleeping and penned letters to her family in the Philippines. When I was in kindergarten and primary school, Beth often helped me with my school work and even knew the Periodic Table. She also knew all my after-school secrets – whom I had a crush on, which classmate I had a quarrel with, why I fought with my sister. But as close as we were, I understood that she was different from the rest of the family. For one, while I slept on a bed in my room, she slept on a mattress on the floor beside me. Looking back, she must have felt uncomfortable sleeping with an outstretched hand just to reassure me that there were no monsters in the bedroom. Also, unless we went out for dinner, Beth usually only ate after we were done. Not wanting her to be alone, I would accompany her at the dinner table. Don’t get me wrong. My parents treated Beth well. We celebrated her birthday, gave her Christmas presents, and took her on family outings to the zoo and holidays in Malaysia. But the fact remained that she was, at the end of the day, an employee, and we were, collectively, her boss. Yet, my relationship with Beth went beyond an economic transaction. I loved her. But I also knew that cleaning my room and ironing my clothes were part of her job. When I was thirteen, Beth woke me up one morning, face riddled with anxiety.

“What’s wrong?” I said, rubbing my eyes. She held out a maroon shirt with a cartoon of Betty Boop printed at the corner.

“Do you like this?” she asked. I knew something was up. People don’t usually give presents with such guilty looks.

“Yes…” I said, trying to understand the situation. Before I could sit up, she pulled my favourite navy blue blouse from behind her with a large burned patch at the front and began to apologize profusely. It dawned on me that in her panic, she had run to the nearby market to buy a replacement before waking me up. That was the first time she burned my clothes and I was surprised to see her so worried. I assured her that it was okay, and even lied that I liked her shirt more than my old one. To show her that I didn’t mind the mistake, I often wore that Betty Boop shirt. I also didn’t question how she burned it (if she was careless or distracted) because I felt uncomfortable that she had to be answerable to me. I never forgot this incident because it was one of the earlier moments that defined our complicated relationship.

Perhaps the lines between an employer and employee need not have to be drawn so clearly if not for the day my parents told me that Beth was leaving us. By then, she had been with our family for thirteen years. That was even older than my earliest memory. I was devastated. Beth had demanded a pay raise because her family in the Philippines needed more money. My parents, who were one of the thousands hit by the economic recession in 2002, couldn’t afford it. Naively, I told them that it didn’t matter because Beth would understand their difficulty. But my parents said that she had given them the ultimatum, and as such, had made her choice.

I was shocked. Why did she have to go “home?” Hasn’t this been her home for over a decade? I couldn’t believe Beth was so money-minded. Didn’t she love me enough to stay? But I knew it was selfish of me to think that way knowing that her family needed her salary. If we weren’t paying her enough, who was I to make her stay? At the end of the day, Beth was hired help. My parents knew it, Beth knew it, so I kept my mouth shut—something I sorely regretted in the years to come, wishing I had fought harder to make her stay.

Without a job, Beth had to return to the Philippines. By that time, she was already in her early-forties. I doubted she was able to find another job, at least not in Singapore, where employers preferred younger maids who were deemed quicker in their thinking and on their feet. At the airport, Beth and I hugged each other and cried until we separated and she entered the departure gates. After that, I bought a life-sized Minnie Mouse doll thinking it could make up for her absence. It didn’t.

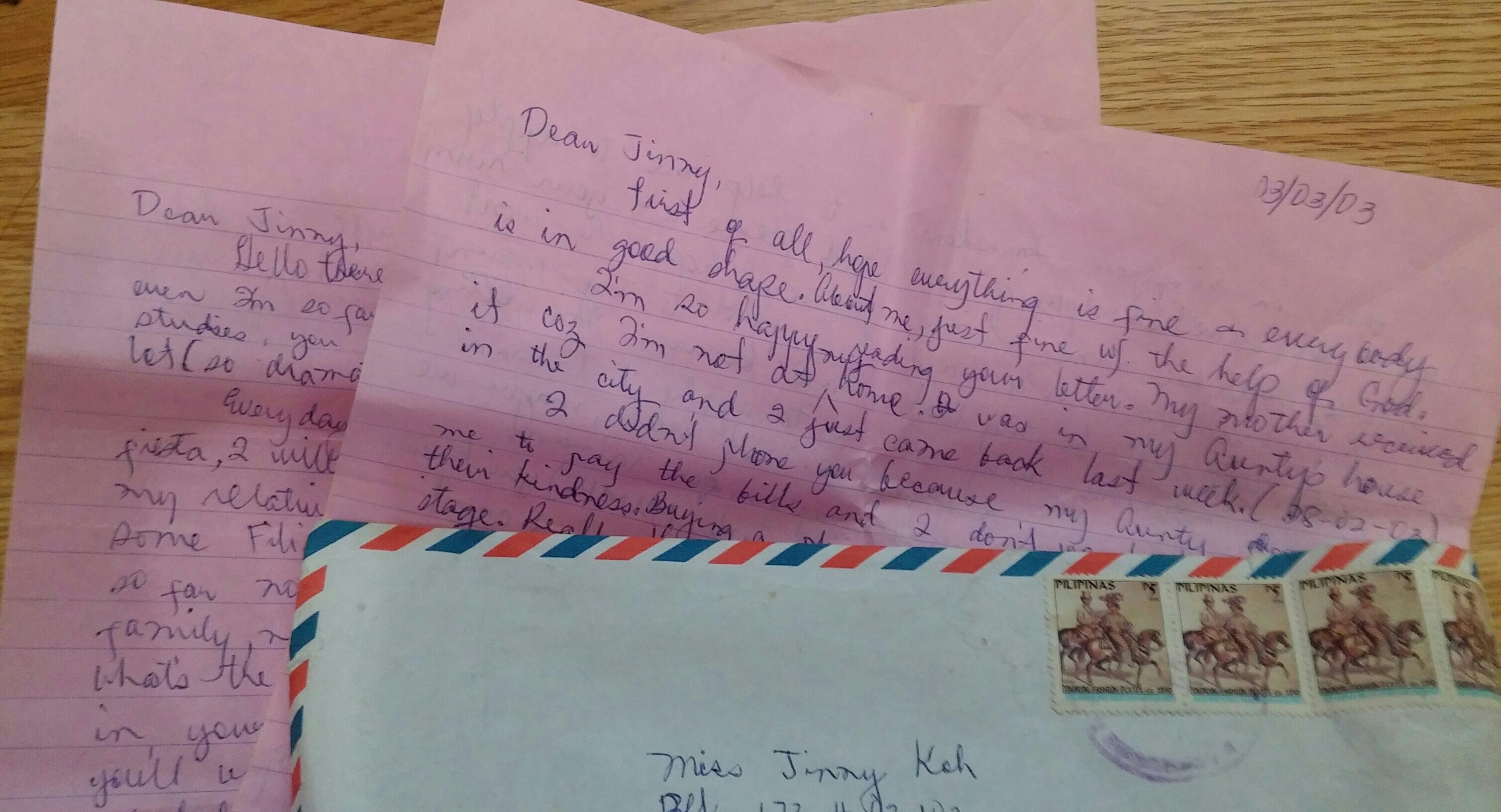

Beth didn’t have a telephone or internet connection in her village so we wrote. I sent her long letters detailing my life. She wrote back too, though not as frequently, and told me that she missed me. Although she was happy to be with her family and friends, she lamented that life was difficult.

“What’s the use of being together if you have nothing in your pocket?” she wrote. “I am just being practical.”

We only kept in touch for a year before her letters stopped. I continued writing but there was no response. In her last letter, she mentioned that she was trying to find work in Singapore or Taiwan.

“I am already at broke stage. Really,” she wrote. “Life here is very hard so I want to try again. Maybe this will be my last chance because I’m getting old, you know.” I learned that at the time of writing, she was suffering from mumps that was so painful that she couldn’t sleep. She also commented on how scary natural disasters were.

“At about 1.57am there’s an earthquake, more or less 2 mins,” she wrote. “I was so scared. For so many years down there (Singapore), didn’t experience anything like this. Down there, no earthquake, no typhoon, nothing. That’s why I’m very scared.”

I kept her letters and even brought them with me to Los Angeles, where I am currently living. Whenever I reread them, I would feel sad. In hindsight, I wondered if her letter had been a call for help to re-hire her. At that time, I had not even entertained that thought because my parents were barely making ends meet. We had moved several times to reduce our housing loans and both my parents were no longer working in their well-paying jobs. To have a maid was a luxury we simply couldn’t afford.

After my sister texted me, I tried to search online for information on Beth. I scoured photos on social media websites such as Friendster and Facebook. I tried different combinations of her name on Google. One night, I spent hours looking through 3,000 photos of Filipino maids in a portal. But like other similar attempts in the past, it didn’t yield any result, especially since her name was my only lead. I had misplaced her address and my parents had not kept her documents. I had thought of embarking on a full-fledged hunt, such as hiring a private investigator, but it seemed too daunting. I didn’t know whom to approach, what to do and if I could afford it. I was also impeded by a list of fears. What is something bad had happened which was why she never responded to my letters? What did I expect after the happy reunion? I had fantasized us embracing each other in tears, exchanging a lifetime of stories, making up for lost time… and then what? Should I stroll into her life after ten years just to satisfy my personal longing and then leave her again? I couldn’t shake off the possibility that my sudden appearance might unsettle her current life, and wondered if my purpose of finding Beth was justified from her point of view.

The more time passed, the easier it became to put my longing aside. Even though I missed her, demands of school, work and other relationships kept me from dwelling on the loss. And after a while, there was less and less reason for recall. I still carry the hope that I’d get to meet her again one day. But for now, time and distance has allowed me the retrospect to understand the complexities of our relationship and, in turn, the ability to accept our separation.

I still dream of Beth in my sleep sometimes. Always laughing, always happy, she looked the same as ten years ago, not ageing one bit: her thick black hair, accompanied with an Alice headband, falling behind her shoulders; her cocoa-brown eyes large and round; her big smile warm and inviting. I cannot imagine her any other way.

About Jinny Koh

Jinny Koh, born and raised in Singapore, now lives in Los Angeles with her husband and daughter. She was the Fiction Editor at The Southern California Review while pursuing her Masters in Professional Writing at the University of Southern California. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Round, The Conium Review, Role Reboot, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, FORTH Magazine, and The Epigram Books Collection of Best New Singaporean Short Stories Volume 2, among others.