You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Back Story

The first time that I wrote something, I was in Japan, eating an egg that I’d hard- boiled in a Hello Kitty kettle with Engrish faux-proverbs all over the side. In my story, the protagonist was prepping for a trashy night out in Sheffield, where I’d been a student before decamping to Kyoto. The protagonist is in her bedroom, in her shared house, kneeling before the mirror. She slicks on eyeliner, straightens her hair and dresses up in studded bootcut jeans and a silken handkerchief top (hello mid-naughties!). In the story, I wrote that she sees ‘latent Nefertiti’ in the mirror. Would I write that now? No. She steps out of the house and the world doesn’t stop.

Can’t they see her, she wonders.

Don’t they know?

She drinks / sweats / dances / drapes herself over friends / boys / furniture. In the club bathroom mirror, she sees Nefertiti: disheveled.

(Subtext: I guess she was feeling young and energetic, and I guess she was feeling ignored.)

She misses Sheffield, even though, in the story, she is there. She feels defined by her outsides, and is searching for her innards. Then she has a fight with her boyfriend, and, for tension, I left the story unfinished…

I wrote this and felt magnificent. I then wrote a story for my Japanese composition class which centered around a locked treasure chest and a skeleton key. I went on to chase this skeleton key through multiple languages — Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and there’s some in-country German to come — with the feeling that I was on the cusp of capturing something. Maybe I needed foreign words to help me articulate it? Something that I didn’t yet have the language for, or even the grammatical structures. Something that I couldn’t yet form with my mouth.

When I got back to Sheffield, I went back to living. I didn’t write again for years.

Inciting Incident

The next time writing stepped out in front of me, I was on an Army base in Germany and my husband was deployed. I was alone in a creaking house so rural that deer and squirrels would stare in at me through the windows. Snow lay unmoving for weeks. Footsteps would appear in it, walking up to my back door and away again. I kept the curtains closed, double-triple-locked myself in, lay awake at night, listening. Downstairs was a basement that could have housed a hostage, could have housed a family. That didn’t help anything. Nor did the boiler, which was old enough to have a hand crank on the front, in case of emergencies. It was atmospheric, let’s say. Gothic.

In the absence of anyone to talk to, I starting talking to myself. I wrote fifty thousands words of a novel about time-travelling lesbian gypsies (I know), and started to tell people about it. Oh, great, they said, relieved — you found something to do.

(If you’re artistic, maybe that explains your personality?)

What a relief for everyone. They were right — I had always had trouble with myself.

Rising Action

I pursued it. A regular writing practice changed me: floor to ceiling, head to toe. I’d always been full of rage, impatience and misanthropy, although — girl time! — I had largely learnt to hide it. I had always had this terrible fear that I was wasting time, even when studying, or working, or socialising like any normal person would. Turns out I was wasting time by not writing. Writing was what my time was for. My rage was for the page. I should never have been carrying a whole life’s weight of thoughts and emotions and memories around in my little head. The page was the place to set them down, walk off.

I channelled all this into my time-travelling lesbian gypsies (I know). I had never made sense to myself, and now I finally did.

But, what comes after pride? I printed out the first draft of my time-travelling lesbian gypsies (I know) in book format, and threaded two treasury tags through as binding. I was travelling up to Edinburgh for Hogmanay and thought, smug as you like, I’ll read my book on the train.

Crisis

Reader, I was appalled. The characters were stereotypes, the plot was incomprehensible and the turns of phrase hackneyed and riddled with cliché. It was a mess. It had become my whole identity, and still, it was a mess.

I had a full-on crisis and then I got serious. I did some online writing courses, I abandoned the lesbian gypsies (I know), and realised that short stories were a better place to start: I could write an ending everyday if I wanted to!

The first piece I ever had published was an essay about the transformative effects of my time in Japan, although I left Nefertiti out. I celebrated loudly, publicly, and then realised that my story hadn’t been included in the issue:

sorry to bother you, but where’s my piece?

Human error, only. It was published in the following issue.

So embarrassing.

I’ve written a lot in the almost-decade since then, and I’ve learnt as much about

writing as I have about myself.

The Protagonist

Protagonists have arcs, protagonists have flaws. A narrative without ups and downs is a straight road to no story at all.

Imagine if Jane Eyre was perfectly…fine?

Characters are allowed to want things, and you are allowed to pursue the things that you want. You are allowed to notice your rut and climb out of it, because that’s what a character would do in a book. Characters make mistakes // mistakes make characters. Practise showing not telling, and you’ll start to understand why you yelled at one of your oldest friends during lockdown, and why you leave such vicious dints when you knock back your bread

There must be a protagonist in a story, just as there has to be (you) a protagonist (you) headlining your own life (you).

Of course, things must happen to / land on / challenge a character in order for them to grow. No protagonist gets out of their story unchanged, or at all: everything must come to an end. These are true things, so knowing them is good. Many people do not understand life at all — maybe your writing will explain it to them. Maybe your writing will explain it to yourself.

The Antagonist

Protagonists need antagonists. (We are into the nitty-gritty of story-telling now.) Start seeing yourself as a protagonist and you’ll become accustomed to seeing your equal and opposite numbers in life, the Captain Hooks to your Peter. Realise that they are necessary to give your story energy: was there ever an activist without a cause? Was there ever a damsel without distress?

Size them up. Consider their role in the story.

Self-doubt is an antagonist, or maybe it is a dragon, and you have a sword.

Lack of courage is an antagonist, but do you want to be a pile of jelly, or a writer? Shame is an antagonist that looks like safety, looks like common sense. Do not be seduced. Hand the world a full colour illustration of your insides and wait. The sky will not fall.

Some real-life antagonists: lack of childcare, lack of money, lack of time, lack of space. Prejudice and prejudice-internalised. An antagonist will mock you for writing and then feel threatened by what you write.

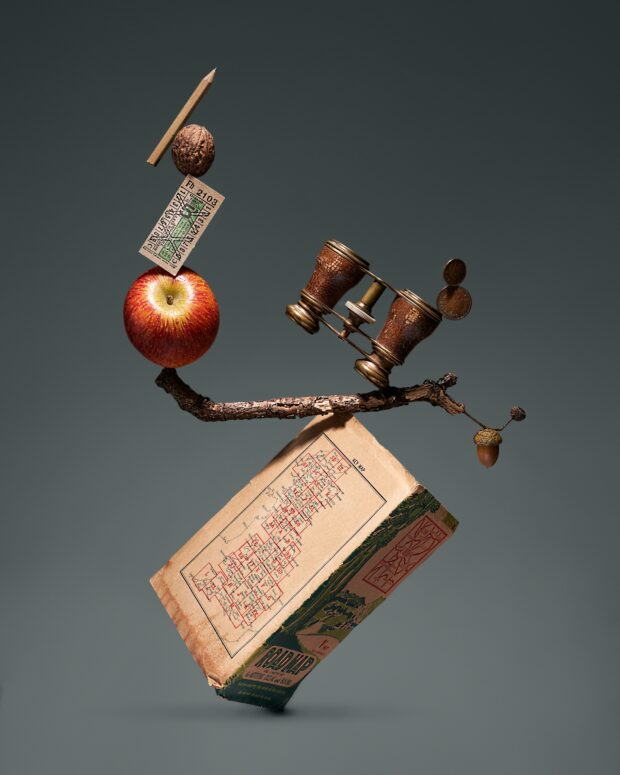

Enchanted Objects

The hot neck skin crawl of handing someone something that you’ve written: put that sensation into your cabinet of curiosities, categorise it as one of your moods. Beside it, place pretending that you’re invisible, that you never wrote it, that this is all an elaborate lie. Everyone takes too long to read things, and also not long enough. Trust me. That stomach squiggle means you wrote something.

If you wrote something, send it out — to have a writing life, you must give it all away.

Line your fears up alphabetically on the shelf. Dewey-decimal your questions, your disappointments, your pain. I was once told by a man at the front of an assembly that we should fail our driving tests to accustom ourselves to failure. Well, I can do better than that — I hope you get stung by a thousand bees and that those bees are writing rejections, because without many rejections you will never learn to both hurt and get back to writing, all at the same time. Rejections are medals, rejections are battle stripes, rejections are proof that you are not afraid to run into no man’s land with only a Twitter handle and your anonymity for cover. Decide that you’re dead and then live.

Live your feelings and also bottle them. Smash your experiences open like geodes, handle them with kid gloves, hold them up to the light. When writing, browse the shelves, stick your hand in to the back, grab the item that shimmers most darkly. You made these objects, and they will make you. Uncork the bottles as required.

Mentors

When my Myers-Briggs classification told me that I express myself most effectively in writing, I thought, well, there you go then. If your suns and moons and risings tell you that you are a communicator, or you are passionate, or drawn to the big questions in life, take that as your permission. (I give you permission to write.) I have all sorts of Capricorn placements, so I can’t help but talk to you directly like this, and an Aquarius sun, so I am speaking both to you and the whole of humanity. Rail against your fate or accept it. Write about this.

Seek out your writing group. Seek your flow state: when I look up from mine and have got a thousand words down and I no longer know what time of day it is, I feel like I could fly. Seek immortality. There are few ways to attain it but the pen is one. Make yourself immortal. Turn yourself into someone who could make Jane Austen laugh at a party. Turn yourself into someone that Casanova would die to seduce. Think of the writers you love and work towards them. Maybe they would be proud of you? Throw your offerings to your gods and despair.

Falling Action

Nobody cares. Truly, nobody cares. I mean this in a positive way. Unless you live under an oppressive regime, nobody cares that you’re writing until you’ve written something to show them, and then they only care a little bit. It’ll be this way until you are such a success that your legal team run Google alerts for fan-fiction and stans camp outside of your house. But you’re still invisible then too, as they’ll watch your public persona instead of you, and judge your future writing on how much they love what you’ve written in the past. You can still slip into your writing and out of the room anytime.

Write something that means something to you and it’ll all be worth it. It’ll even be enough to brazen through the cringe of having to send your family the link to a piece where you talk about thwarted orgasm, or the like. See wunderkammer: embarrassment, shame. Feel the shame and do it anyway. It’s not like they had the guts to write a story, is it?

Cultivate a false face, so you don’t have to look anyone in the eye over lunch ever again.

Symbolism

The pen is a magic wand; or a penis; or a conduit for God; or a blue inked Biro you got in a pack of ten; or it’s a pencil that you nicked from work.

All that is up to you.

Sometimes you’ll think you’re writing something really profound, and sometimes you’ll just be really, really tired.

Point of View

You have one. Take up space with your thoughts, follow the thread to the end. Reassure people that its fiction, if necessary.

Write about your world: write about yourself. You are not a narcissist, it is called being straight with the world, for once. Tell yourself all the reasons why the world doesn’t need to hear what you think, and then smack those reasons in the face.

Exposition

I am telling you this because I want you to write. I want you to meet me on the mountaintop with a paper trail flying from your feet and a working knowledge of yourself in your hands. If you write your story, you can keep it from descending into tragedy, unless that’s what your characters need. Keep it from ending until it ends.

Denouement

Things do actually end. They must, else the story is incomplete. But do you want the pages of your book to be written by others?

Write it as if inevitable.

About Lyndsay Wheble

Lyndsay Wheble's work has appeared in The Mechanic’s Institute Review, Litro, Spoonfeed, Belle Ombre, as part of Extinction Rebellion’s Writers Rebel series, on BBC radio, in the Oxford Writer’s Circle’s ‘Love with a Twist’ anthology, and elsewhere. She won the Reflex Fiction Prize in Summer 2018 and shortlisted for the Yeovil Prize in 2015. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Oxford Brookes and is an Associate Editor for Short Fiction magazine.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)