You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

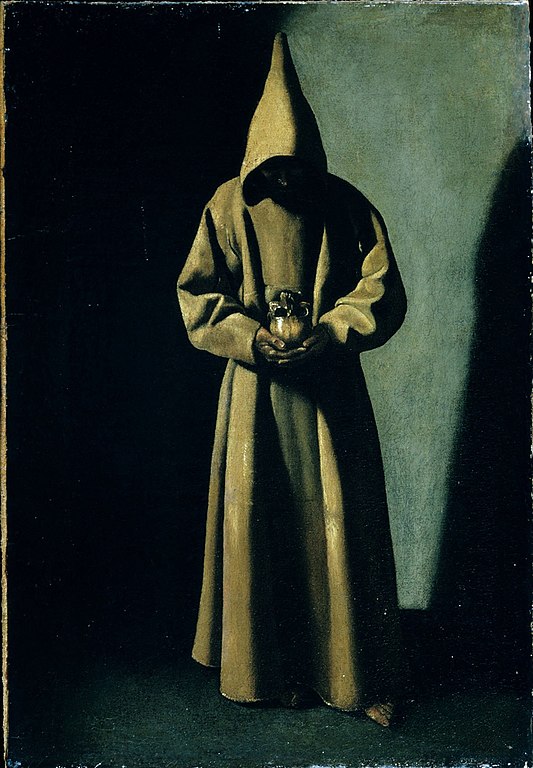

A blue-grey tomb of a mountainside, with a dozen or so buildings as a lichenous stretch across its top – that was their little world, the monastery. Perched in the cloister walk, two monks sat deciding what Heaven looked like. “If we,” Brother Pachomius was saying, in his high drawl, thinking the words at the same debilitating pace at which he spoke them – “Yes, if we are made in the image of the shadow of God, we may still guess at his form because of our own.”

Brother Anthony, his companion, square, short, with a craggy nose and cloudy but stern and matt black eyes, sat very still and did not reply. He was used to his Brother’s rhetoric.

“Surely, then, surely, our cloisters must be shadowy images of heaven’s. We are imitations making imitations.” Heaven, then, Pachomius was sure, was a monastery.

Anthony drank some beer, savoured the taste, and thought about his friend’s argument. “Different to this, though, I think. There would be differences.”

“Yes. It would be perfect.”

“How?”

Slowly, Pachomius managed, “I’m not sure.”

“There’s no sin in imagining. You must have imagined heaven, Brother. When alone, and tired of this. Sometimes you wonder.” Here he glanced upwards and clenched his jaw. “As I say: there is no sin in it.”

“Quite right, Anthony. Quite right. No sin at all… It is a way of bringing one closer to God. One may know a man by his house, after all, mightn’t he?”

The sound of rain gently beating at the stone walls of the Brothers’ own house gave them answer, along with the wind, which had picked up, and was sounding a shrill hiss through the halls. They both noticed it. One never got used to the wind – it grated on them all, there, on the mountain, and made them grind their teeth.

“So what does it look like?” Anthony muttered.

“Well,” began Pachomius. He considered. “Bigger.” He seemed displeased with how this had come out and shrank back from his Brother.

“Obviously.”

“Oh. Yes, of course. Yes. Bigger. I mean to say, grander. For it would have to accommodate so many.”

“And yet it would never be full.”

And so they talked for a little while more of the architecture of Paradise, of its materials, and plan, of the thickness of its walls, the design of the forge, of the church; but they were soon called to Sext by the bells.

*

The two Brothers were in the garden, on their knees, plucking and pulling at weeds, tending to the vegetables, the dirt worked into the grooves of their hands and their nails completely black. It was a foul, unwieldly day that stank with the smell of thunder, and made green things blue. They had both thought on the subject of heaven, and quickly fell to talking about perfection. In this life, as Pachomius put it, without quite achieving eloquence, “Even if we strive to walk upwards, always along the best and true road, even if we do not stumble once, we still muddy our boots.”

Brother Anthony was not happy with this, and sought to express the thought himself: “Heaven’s perfection is divine perfection. It is unachievable for man and outside of heaven, by its nature. We aim to be perfect, but only as we can be.”

“Exactly, yes. The perfection of God awaits us; we know it by sight and not by touch, it is the image we seek to carve of our own perfection. Although, Brother, remember Jesus’s Amen – ‘be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly father is perfect’.”

Matthew 5:48. “That, Brother, is why we remove ourselves from the rest of men, so we may better try.”

“The perfection we reach is a perfection unknowable to them.” Here he gestured with a soiled hand to the valley below, unseen from their height, for a thick, grey shield of cloud and mist cut off the peak of the mountain.

Anthony nodded. “They have no time to contemplate.”

They both meant more than was said, but neither was able to fully convey his thoughts about that place. They turned from it. Anthony wondered what the perfect, earthly monastery would look like, and they discussed it, working around the difficulties intrinsic in mortal things, attempting to refine their home and make it pure. But soon the rain from higher clouds grew so intense they could barely see. They went inside, quickly, while the mud was washed in rivulets to lower slopes.

In his dorter, Pachomius found that the room had its problems: bricks had chipped and black mould was accumulating slightly; the window was not quite sealed, so that the horrid wind was in the room, disturbing him like distant voices in the dark. Things closed in on him, and he did not sleep before Lauds. In the morning he asked for mortar.

Anthony saw faults even as he left the garden, but he was, on the whole, undisturbed by them. Even so, their conversation stayed with him, and he lay awake for a while, with a mounting want and expectation that something should happen.

Pachomius fixed his window, and started to informally repair the monastery at large. He eventually asked if he may devote some of his working hours towards a comprehensive system of upkeep: a request which was granted.

*

The season wilted and the rains came finally in earnest. Brother Pachomius worked on his repairs as if it was his nature: he retiled roofs and talked to himself. He had no idea of the perfect monastery outside of fixing the one he already knew, and had not considered the possibility that his home did not offer the chance of an ideal, even if ideal itself; he simply found faults, and eliminated them. Conversely, Anthony knew less and less of their home. He strove to contemplate perfection in its variety of constructions, and committed himself to creating something free from the interference of others. He built a monastery in his mind that grew in sharpness and clarity, and, after a while, in truthfulness. Very little at all disturbed him; when he did pull himself to the present moment and look about, at prayer, or at their meals, he saw the edges of things glittering into pieces. And this vagueness and sense of unreality steered him to the solidity of his creation, to the comfort of its laws – and thin lines crept into his face.

On completion of his project, he fell into a fever. He was found, quivering and unresponsive on the floor of his cell, flecks of spit at the edge of his mouth, his eyes bloodshot and open. The Brothers moved him to the infirmary, fed him soup, gave him medicine and eventually let him rest. In this obscene, hot sleep, he raved and was not himself.

Brother Pachomius went to see him, lain up in bed, to give him God’s blessing and wish him well – a task which he had found difficult, not least because it separated him from his labour, which he now saw as intrinsic to his prayer; he wished to follow Paul’s instruction to the Thessalonians to “pray without ceasing”. He worked until exhausted, and all the while he would pray “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, for I am a sinner”.

Anthony had done nothing to acknowledge his visitor except widen his eyes, which were horrible to look at: they bore little resemblance to eyes with a soul behind them, and were purple. He was still feverous: pale, vein-ridden and sweaty. But more upsetting to Pachomius, more disgusting by far, was the obvious impression that despite his condition, Anthony recognised him, and, if only he had strength to look, he would see in those mad, apparently void eyes, recognition and understanding.

Anthony grabbed his arm, weakly, but with such purpose that Pachomius knew he would not move until it was released. His Brother stared at him, harshly, freaked, and said, with a rasping voice, “Us!” He tightened his grip, and a look of unmitigated violence showed, suddenly, in all the features of his face.

It was some weeks until Anthony recovered. He remembered that desperate “us”, but, at first, he could make little of it. This was not the case for Pachomius, who had been greatly affected by their meeting.

*

Even when there was sun, on those short winter days, it was cold in the monastery – the wind felt like it was stripping everything down to its base. Water sat in pools, spotted over the land and in courtyards refusing to dry: some of the Brothers glimpsed their reflections and smiled pityingly at their weathered faces, so different to how they remembered them.

Anthony was tending to the mill and grain. His sturdy, ruddy face was quite still, fixed absently in an expression that, had it been conscious, would have been called a sneer. He bit at a parsnip. The Brothers were causing him a problem. He was struggling to find a place for them – and for himself – in his perfect creation, struggling to imagine someone worthy enough to walk in his garden, to imagine footsteps in his hallways, so well-laid to take them, and to picture grime building up on the sills.

The bells rang several times, and the long night came.

Pachomius could not sleep; he had not been able to sleep for some time. He was gaunt, and his gangly, hawk-like body made his weight loss appear vile. He had been worrying over the Brothers, and worrying over his work, and so wandered the courtyard rather than stay in his cell. It was a clear, bright night, singularly coloured: everything was blue; and the light was flat, so the shadows and the patches of uninterrupted moonlight were gradations, barely variants, of the same, full, dark blue. It looked like he was drowned, except that the moon was in the sky, ugly and implausibly white. He found that he hated it, and looked instead at the columns of the cloister, some of which he had repaired recently. It pleased him to look at his work. The wind clawed through the courtyard – it swiped at his thoughts and cast them off like dead leaves. It blew him out into the cloister, lifted him above his dire, obsessive self, and floated him down the halls; he walked like a follower, hollowly and confidently, for his path was known to him. He stopped by the door of Brother Benedict. He went in and saw him asleep. The room, Pachomius noticed, was very well kept, and this, for some reason, filled him with joy and a sense of the correctness of everything he did. Quietly, he took off his cowl and neatly folded it several times into a rectangle. He went to the bed and placed it over Benedict’s head very firmly. His brother woke with an incredible, vicious panic, lashing out, desperate and struggling – he screamed into the coarse cloth. Pachomius did not look down, but kept his gaze on the wall in front of him, trying to make out the bricks, and saying over and over “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, for I am a sinner.”

*

The Brothers were no fools, and believed that Benedict had been murdered. They banded together as much as they could, while the abbot told them to be wary and watchful, and sought to establish what had happened.

During this time Anthony withdrew increasingly into himself. The more he was in company, the less he felt part of it. The outside world appeared far away, and none of his business, and so he explored the workings of what could be known to him: his thoughts and actions, and the ideals he had created. He saw the image of what it was to be perfect clearly, and set against it his own faults were dreadfully apparent.

When walking alone to go to get more tools for the roof of the barn Pachomius passed Brother Sabbas who had fallen asleep by the sheep-pen, idle. Without thinking much why he did it, he put his hand over his mouth and his hands round his throat – Sabbas woke, astonished, and bruised and cut his attacker. Pachomius hardly moved. Bright pink marks were left on the corpse’s neck, and by the time it was found they had changed into shiny blacknesses. Some Brothers were sent to fetch villagers from the valley, to pay them if necessary, for protection and assistance.

Pachomius had renounced himself, given up to something larger, and more persuasive – a powerful numbing feeling of concern for all creatures, which gave him peace. The next day he killed Brother Gregory, who did not struggle at all.

And so, by order, everyone spent their time together, which they were not used to. It began to drive them slightly mad. There was no word from the village.

*

A storm broke over the height of the mountain, making the sky dark and thick and unfriendly. It rained harsh rain and rained constantly, like a deluge. The Brothers were always wet, and many slipped on the flagstones as they went to the refectory, breaking their bones and scraping the skin off their knees.

In the dim afternoon, Brother Pachomius appeared in the oratory porch, silhouetted, black-brown against grey, framed by the doors, rain confusing the landscape behind him. He had come from the barn and was soaked through. He held a hammer. The several monks in the church went silent and stood still when they saw him in the doorway, an apparition of menace, and they were afraid. He came in, and with bright, meaningless eyes he looked at his Brothers: his quick steps echoed around the building.

He reached Brother Francis. Nobody had moved. The hammer was raised, Pachomius’s arm was straightened and stiff, his smile wide, his face in highlight and full of shadows. In the moment before he cracked into his Brother’s skull, bells started to chime. It was the wrong time for them, and they were badly wrung, weak, dissonant, sporadic, but the noise roused the Bothers from their horror. The hammer broke into Luke’s brain, separating and discarding fragments of bone, splintering them into his skin; he collapsed, blood dashing in small drops on the cold, smooth floor. The monks approached Pachomius, but he swung at them and shoved them off painfully; he almost growled. He brought the bloodied hammer down on the corpse, and smashed it into Luke’s head, flattening a cheek bone and rendering the face unrecognisable – blood wept across what features were left, and over the yellow-white protrusions of teeth and bone. He was tackled to the ground and his weapon stolen. They bound his hands together before hoisting him to his feet, shouting, louder than he had ever known them.

He still fought; he could not rid himself of the feeling that they were disastrous, an affront to all that was graceful and of sense. They forced him outside into the rain, into the grey hatred of the mountain weather – the bells could still be heard, just, buried in the wind. An unexpected group was gathered outside the church: the people from the village, arrived at last, led by a few of the Brothers. But they did not look at Pachomius or his captors, they did not notice this absurd prisoner with a wild face and stained hands; they looked instead at the bell-tower.

With a halo of lighter clouds behind it, the tower was an incredible object, stark and amazingly defined. Not quite half-way down, dangling from the bell’s rope, and swaying in the wind, was Brother Anthony, who had hanged himself. The swinging of his body’s bulk, its scraping over the stones of the church, caused the gentle movement of the bells, and directed their otherworldly, off-sounding song.

The Bothers were unable to take in the full tragedy of the sight; their faces betrayed the blankness of their grief. They gripped Pachomius tighter. He alone was truly moved by the sight of his friend, dripping and broken: he cried in wilful, rapturous joy – he, alone, found sanctity and love in this black terror. The Brothers dragged him to the crowd, while he squirmed and smiled and shouted; his Brother had raised himself to a state beyond this doggedly imperfect place, and was set apart, untouchable by wear and ruin: he had split apart from his faults and now gazed infinitely, outside the storm, on true perfection – he saw heaven, God’s work, unimprovable, he walked in the garden of that sublime place, part of it. As the crowd took him and led him down the mountain, beating and spitting at him, Pachomius continued to weep, though the wind and the rain blasted the tears from his eyes. He was unaware of the little life going on about him, unaware of the sharp descent, for he knew that soon, like his Brother, he would join God’s kingdom, and those who were perfect.

About Samuel Graydon

Samuel Graydon is a commissioning editor at the Times Literary Supplement. He writes regularly for the paper on a variety of subjects, from quantum mechanics to folk music. He is currently working on a non-fiction book. His short fiction has been long-listed for the Alpine Fellowship.