You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Can you tell the gender of an artist by looking at their paintings? Know the sex of an author by reading her work?

Bastille Day is a day celebrating the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. Although in 1789, when it was proclaimed, women were not considered citizens. It wasn’t until 1791 that France’s first feminist, Olympe de Gouges, published a declaration recognising women as citizens, and it would be a further 54 years before France would grant women the right to vote. I asked writers, artists and a gallerist how much much has changed since then, and what it means to be feminine?

Sylvie Bailly (writer and gallerist): My grandmother was born in 1900 and she received her first chequebook when my grandfather died. And that was in 1979!

Litro: I guess to pay for his funeral.

Sylvie Bailly: The problem with how a woman finds her place in these big cities [Bailly came to Paris from Vienna when she was seven]…is how you can be feminine as well as a working woman in a big city. Because we are not women in the countryside. We are business women. And that is the point, we make efforts to be feminine, but somehow we have to be active, modern women.

Litro: We were talking earlier about brands and how they operate as sociological symbols. When we do not have time to reconnect with nature, with our feminine side, when we’re more and more taking on masculine roles, then fashion becomes a stand-in for what we lack. We have the money to buy a brand that is a symbol of femininity.

Sylvie Bailly: We say in France a panoplie. I don’t know if it’s the same in English; we buy an outfit, but it doesn’t mean that we are feminine. There are some women – they can’t walk in very high heels – and in Paris sometimes it’s strange how a woman walks.

Litro: Like a wounded animal.

Sylvie Bailly: Yes, yes. A wounded animal!

Litro: And what does it mean to be a woman today?

Sylvie Bailly: In the past the way a woman was clothed was dependent on her origin, religion, social status. And now you take modern culture and put it on old culture and it’s strange somehow. You know what I mean? A work of art, it’s like a message in a bottle. Messages from the ancient world somehow.

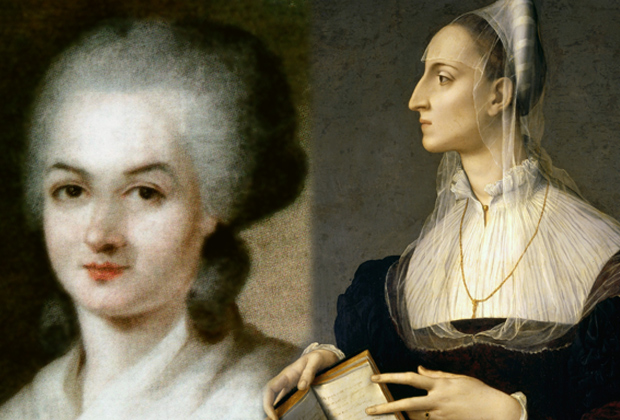

Litro: It can be understood by all without the barriers of language. There is a painting in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. It’s a portrait by Bronzino of the poet Laura Battiferri. It’s not one of his well-known paintings. He painted for the Medicis and normally did very stylised portraits, but this one was striking for other reasons. Later I did a little research and found out she was married to a sculptor and couldn’t have children, so this caused her some sadness which she funnelled into her poems. But without knowing all this, the first time I looked at the painting there was something immediate and powerful and extreme. She has a very fierce profile, a little like a crow, and these large, intelligent eyes. And her hand is holding this book and the way it’s bent it looks almost like a claw. And of all the amazing paintings and Renaissance sculptures in Florence, Botticellis and Michaelangelos, it’s strange, this is the painting that stays with me.

Sylvie Bailly: That’s what’s interesting about your paintings, too. It is aesthetically pleasing, and yet it’s unsettling. There is a woman on the beach, but look closer, she has almost no clothes on and there is this helicopter on the the horizon.

Litro: Well, thank you. I try to…I don’t know if I succeed always…but that is the thing about painting, this ability for it to speak to us after many years. This painting was done in the 16th century, but in it Battiferri seems like a feminist, like Olympe de Gouges. She had independence. She was a poet and she couldn’t have children, that route wasn’t open to her so she wrote.

Sylvie Bailly: Olympe de Gouges was from a not really poor family from the south of France. She was born in Montauban. Her mother was educated at the same time as Jean-Jacques Lefranc, who was from a very wealthy family. Because their families were close, they spent all their time together when they were young and they were in love. When her mother became pregnant he didn’t support her and never recognised Olympe as his child. Later he became a famous author and married a wealthy woman.

Sylvie Bailly: Olympe de Gouges was from a not really poor family from the south of France. She was born in Montauban. Her mother was educated at the same time as Jean-Jacques Lefranc, who was from a very wealthy family. Because their families were close, they spent all their time together when they were young and they were in love. When her mother became pregnant he didn’t support her and never recognised Olympe as his child. Later he became a famous author and married a wealthy woman.

Litro: That’s interesting because Battiferri was also the illegitimate child of a wealthy man. Although her father recognized and eventually legitimized her, it may have contributed to her need to be recognized for her art.

Sylvie Bailly: Olympe’s mother’s name was Olympe. She adopted her mother’s name to honour her. Lefranc was immensely rich and famous. She wanted to have the recognition of her father, and that’s why she adopted de Gouges with the noble prefix because she wanted to be appreciated by her father, who was now a famous author and an enemy of Voltaire. Voltaire was one of the Siècles de Lumières [a European intellectual movement for equality,1715-1789, whose members included David Hume and Thomas Jefferson].

Because her father never gave her mother money to educate Olympe, she became revolutionary and aware that there must be more equality. She became a humanist. She was the first woman in France to fight against slavery. She didn’t only have feminist ideas. She wrote a play L’Esclavage des nègres which was performed at the Comédie Française – because when she left Montauban she came to Paris and was fortunate to have wealthy friends who helped her bring her play to the Comédie Française. But the problem was that when slave owners visited Paris they all attended the Comédie Française. And her play, which spoke out against slavery, became a big scandal.

She was also the first woman to propose the right of divorce, fought for more independence for women, the welfare state and abolishment of the death penalty. She campaigned for access to hygienic maternity wards for the poor. She grasped so many important things which are the basis for our modern world.

Litro: She was a vanguardist.

Sylvie Bailly: Absolutely. She attended public academies, but really she educated herself. And Mirabeau, who was a famous French politician said – so many intelligent ideas coming from an uneducated woman. She wrote many socially-engaged plays which encouraged political change.

I am surprised that she is not better known outside of France. As the Revolution progressed, she became more outspoken and finally she was arrested for her writings. The prosecution claimed that her writings stirred support for the Royalists, but de Gouges stated she had always supported the Revolution. At this time the Jacobins wouldn’t tolerate opposition from intellectuals. De Gouges was sentenced to death on 2 November 1793 and was executed by guillotine the following day.

Sylvie Bailly Formerly a lawyer specialising in international law, Bailly is now a gallerist and the author of many non-fiction books, including Des siècles de beauté, which discusses beauty in it’s political and religious context, and as a counterpoint to male hegemony. The exhibition Elles: Chinese Women Artists runs in Galerie Olympe de Gouges from October 1 to November 7.

Next week: Part II – Conversation with Jean-Luc Maxence about Jung, celebrating the difference between men and women, and the impossibility of writing genderless fiction.

About Mia Funk

Mia Funk, Mia has received many awards & nominations, including a Prix de Peinture (Salon d’Automne de Paris), Thames & Hudson Pictureworks Prize, Sky Arts Portrait Artist of the Year, KWS Hilary Mantel Short Story Prize, Doris Gooderson Prize, Aesthetica Magazine's Creative Works, Momaya Prize & Celeste Prize. Her paintings have been featured on radio and television, at group shows at the Grand Palais, and are held in several public collections, including the Dublin Writers Museum. She is currently working on portraits for the American Writers Museum, completing a novel and a collection of linked short stories.