You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

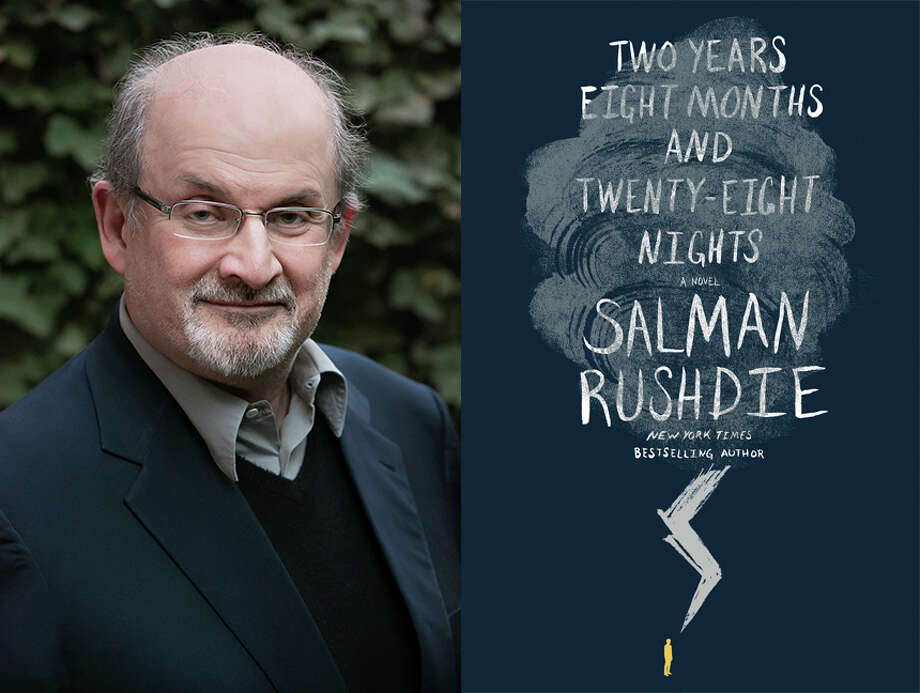

After all the time he spent thinking about and writing his autobiography, Joseph Anton: A Memoir (2012), Rushdie has said, half-facetiously, that he had had enough of truth and its attendant high seriousness, longing to write something entirely fictitious. The result is his latest fantasia-like novel whose symmetrical title, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, is a Julian calendar apportioning of the legendary 1001 nights of Eastern lore.

Currently a resident of New York, Rushdie wanted to see what would happen if he hurled the Persian stories of his childhood at the Big Apple. The novel crosses War of the Worlds with Aladdin for a showdown at the heart of New York – a sign that the anxieties of 9/11 fiction are being playfully assuaged.

When the veil between the spirit world and humanity is ripped at the start of the plot, “strangenesses” begin to manifest themselves. Geronimo, a humble gardener, begins to levitate a few centimetres above the ground on a permanent basis, a Kafkaesque fact which makes menial tasks like going to the toilet something of an acrobatic feat. In another part of the city, a graphic novelist encounters a mysterious entity that turns out to be the incarnation of one of his most sinister creations. This and many other captivating oddities occur. Two ancient Eastern philosophers come back from the dead to wage intellectual warfare with each other, providing a little gravitas in this otherwise phantasmagoric firework of a novel. Ghazali, a conservative theologian, is countered by the twelfth-century thinker Ibn Rushd, an obvious onomastic stand-in for Rushdie. Ghazali argues that “faith is our gift from God and reason is our adolescent rebellion against it”, a belief which his adversary refutes by claiming “that in the end it will be religion that will make men turn away from God. The godly are God’s worst advocates.”

With such a fancy-packed plot, it would be impossible to conclude, however, that the novel is a straightforward championing of secularism and reason over the godly and the irrational. Rushdie quite obviously relishes the imaginative mayhem that is unleashed by the invasion of the spirits. Although order is restored at the end, the novel draws its creative juices from chaos, unreason and magic thinking. The paradox is that the same irrational thought that led to the fatwa against Rushdie fuels the magic realism that drives his novelistic enterprise.

The end of the novel reframes the story as a historical narrative recounted by beings from a distant future looking back on our time as the mythical past. These future humans have managed to eradicate the irrational and the animal drives, inhabiting an entirely rational society devoid of iniquity and violence. The downside is that they lose the capacity to dream and think imaginatively.

This deterministic vision of creativity as an impulse born from violence seems somewhat reductive, if not downright contradictory. Surely the complete repression of our reptilian urges would on the contrary lead to more intensely active compensatory dreams? The eutopian ending therefore seems flawed both as a potentially perfect world and in its authorial conception since its does away with the Freudian notion of the return of the repressed and the long-established role of sublimation in the creative process.

Rushdie’s novel has been both praised and slighted in early reviews for its fanciful fling with modern superheroes and folklore. It’s true that there are times when the novel flirts with Avengers-style aesthetics and others when it adds to the Avengers cast to such an extent that it feels like you are reading the novelistic equivalent of an Erró collage.

Alongside these is Rushdie’s amusing marshalling of surreal-absurdist writers and visual artists. It’s not hard to spot the references to Ionesco, Beckett, Magritte, Gogol and Buñuel in the following evocation:

In a French town the citizenry began turning into rhinoceroses. Old Irish people took to living in rubbish bins. A Belgian man looked into a mirror and saw the back of his head reflected in it. A Russian official lost his nose and then saw it walking around St Petersburg by itself. A narrow cloud sliced across a full moon and a Spanish lady gazing up at it felt a sharp pain as a razor blade cut her eyeball in half.

The novel extends this juxtaposing technique to its vision of humanity. As Geronimo puts it: “We are a little bit of everything, right? Jewslim Christians. Patchwork types.”

In the end, Rushdie’s tongue-in-cheek humour and vitality make the novel a stimulating read, regardless of whether or not you are drawn to kaleidoscopic intertextuality and comic strips. If anything, the exciting imaginative maelstrom that Rushdie stirs up in this novel is ultimately a bit tame. His narrator reminds us more than once that the jinn characters he focuses on are highly sexed beings as well as tricksters and metamorphs. It’s a pity we’re not given more samples of their surreal prowess as this would have interestingly countered the idea that violence is the main source of creativity. Compared to Angela Carter’s The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr Hoffmann and J. G. Ballard’s The Unlimited Dream Company, the sexual imagination at work in Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights seems just a little too genteel.

Salman Rushdie’s Two Years, Eight Months & Twenty-Eight Nights is published by Jonathan Cape for £18.99.

About Erik Martiny

Erik Martiny teaches literature, art and translation to students at Henri IV in Paris. He writes mostly about art, literature and fashion. His articles can be found in The Times Literary Supplement, The London Magazine, Aesthetica Magazine, Whitewall Magazine, Fjords Review, World Literature Today and a number of others.