You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

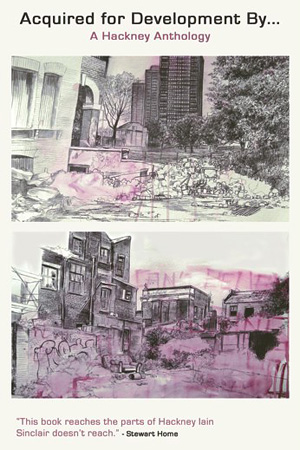

Acquired for Development by… is an anthology of journalism, poetry, and short stories about Hackney, a borough which has divided opinion; depending on who you listen to, it’s either a crime-infested shithole or the epitome of the new grunge cool. With this collection, editors Gary Budden and Kit Caless aim not only to depart from the official version of events propagated by the pro-regeneration camp, but also to steer away from the already well established counter-narrative, led most notably by writer and long-time Hackney resident Iain Sinclair. What they purport to offer is merely a “snapshot” of Hackney as it currently is, which is all that is possible since Hackney is constantly changing. In their introduction, they write, “Not only had physical space been acquired for development, but history, culture and memory also.” This anthology, then, is an effort to reclaim part of that personal and cultural history—all 25 writers, Budden and Caless included, have lived, or are living, in Hackney. The pieces are divided into geographical sections, highlighting the importance physical landscapes play on the lives that inhabit them.

The first piece sets the tone for the rest of the anthology, which is generally heavy on metaphor and parallels since many take a satirical view of goings-on in Hackney. In Gareth Rees‘s “A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes“, a man has a love affair with a tall, dark, femme fatale of a pylon when family life gets rough—the baby crying, the wife nagging. In truth, I think this is a gimmicky concept that has been done, so it shouldn’t work, but funnily enough, does. It’s not the love affair but the reason for the protagonist’s clawing desperation for something, anything, to make things better—having reached a point in life and realising that it’s not where he wants to be—that is believable. Of course, it’s also possible that his eroticising a pylon has to do with him dipping his eyeballs in the same cataract eyedrops he’d bought for his dog, but since this anthology is a lighthearted study in psychogeography, it doesn’t take much to imagine that we may take comfort in our physical surroundings when the going gets though. After all, falling in love with a pylon rising out of the marshes is only a microcosm of falling in love with a place, as many of us have done and still do. What really carries the piece through, however, is its humorous voice. According to his biography, Rees has written comedy before, and it shows, with some great turns of exaggerated phrase personifying, endearingly, what is essentially an inanimate industrial object:

I went to her, heart pumping. Stood dead centre between her four legs and gazed up. I gasped at the interplay of lines. The poetry of infinity in her delicate spirals of steel. She fired sunbeams at me through her gaping geometry. I laughed in response. I marvelled at the essence of her, trembling with electricity. I touched her legs, each clad in a garter of barbed wire, thrilled at the thought of the volts running through her.

For a moment I imagined her in a black leather miniskirt and I felt an enormous, surprising erection.

As with all forbidden love affairs though (with the exception of Twilight), it doesn’t last. This being a collection built around the theme of redevelopment, I’m sure you can guess how it ends. [For more of Rees’ work, visit his blog, The Marshman Chronicles.]

Another short story I liked was “https://” by Lee Rourke, whose debut novel The Canal won the Guardian‘s 2010 Not The Booker Prize. It is a short and effective piece about a relationship that doesn’t work out, set in our highly technological world which has the unique ability to seduce two people into feeling a false sense of closeness over physical and geographical distances and to afford the illusion of neatness that is, in fact, impossible to achieve in real life. “__ __ is now listed as single,” reports the protagonist’s Facebook feed, as if the messy process of breaking up can be whittled down to a specific time and place. Also particularly well done is the crackling atmosphere that lights the piece, every human action so dependent on modern gadgetry that even our brains fire off “pulse-bleeps of neural activity” like an “electrical surge”.

Generally, however, I struggled to get through the first half of the anthology, but the second half more than makes up for it. Gary Budden‘s “Tautologies“, in particular, is a wonderful coming-of-age story describing the protagonist’s increasing disillusionment with the life he used to lead, the life he is still semi-sort of leading. We feel the yawning chasm between him and his previous self, him and his friends, him and the punk nights and squat parties he used to frequent. And yet, at the same time he confesses, “My enthusiasm has been waning lately for such things, but I wanted to get back into it. Missed the camaraderie, the sense of belonging, sometimes.”

The gist of the story is summarised in this paragraph:

Andrew was keen to go ahead putting on shows and events in the squat. I was flitting between commitment and indifference. I was trying to mix more outside of the immediate circle, felt tired from vegetarian arguments and undiminished anger. How many times can you explain your position? The circle I had drawn around myself for protection had become a noose around my neck. At times I hated the things I loved and everything that had once set me free now wouldn’t let me go.

But there is a time of everything. It’s easy to feel that we can’t turn our back on the “selves” we were because it would be tantamount to admitting you were wrong, but just because a way of life is no longer right for you doesn’t mean you have to deny it. Budden’s protagonist later realises that the crazy party nights will “always mean the world to me”, but “I could evolve, with bridges intact behind me.”

I also enjoyed David Dawkins‘s “A Hackney Triptych“, each section looking at the recent spate of strange, sexually deviant acts committed by the manager of the Pages of Hackney bookstore (it might amuse you to know that Dawkins is the real-life manager of the same bookstore), who has not yet been caught, through the eyes of different members of the community. I kept reading, and reading again, trying to extract some sort of larger meaning from it—I’m not sure whether I found it—because Dawkins has a darkly comic voice that eggs a reader on. Some of my favourite writing in the anthology features in this piece.

I was also pleasantly surprised to find a spatter of dystopian short stories in the collection. “The Battle of Kingsland Road” by Paul Case tells the fictional future history of a clash between Stoke Newington’s Rising Dawn Army and the Hoxton Liberation Army, who later realise that they aren’t so different after all and choose to join forces against the establishment. It’s an interesting premise, but a bit of a letdown—the problem, I think, being that the vehicle through which the story is told—manifestos, letters, and transcripts—fails to engage. Similarly, Ashlee Christoffersen‘s “2061“, which depicts a society returned to a new feudalism, doesn’t quite succeed in making me believe in its world. Kit Caless‘s “The Finest Store“, about a world in which high street homogenisation is taken to its extreme conclusion, and Rosie Higham-Stainton‘s “Paper Corpse“, about a nonhuman creature living in the cellar of a derelict building which is finally demolished, are more satisfying. The latter also reminds me of Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, of people who fall through the cracks and fissures of society.

The flash pieces peppered throughout the anthology break up the longer stories nicely. “Electric Blue” by Ania Ostrowska is about an unexpected encounter with memories of an ex-boyfriend—not in person but with his bike, now tainted with mauve: another woman’s incriminating touch. I also particularly enjoyed “Fibre Optic Tree” by Anita Demahy, which juxtaposes the two sides of Hackney with unforgettable images:

Dad’s ninth story apartment rests in a Hackney project complex among the stars

One single compartmentalized unit of drugged and drunken bachelorhood

I am not a big reader of poetry, but Molly Naylor‘s two poems, extracted from her collection Whenever I get blown up, I think of you—”Pavel’s Smokes“, about working a bar on a Friday night, the English and the immigrant’s attitudes to work standing out from each other in sharp relief; and “Fortune“, about being young and dreaming big in a big city, only to face disillusionment—are profound in their narrative simplicity. Two lines in “Fortune” stuck with me—one in the middle of the poem:

somebody once said we were something

and we haven’t forgotten yet.

And the other at its conclusion:

Someone once said we were something

and we haven’t learned anything yet.

The journalistic pieces, though about fascinating subjects—the Turkish Alevi community, the River Lea boat community’s existence threatened by British Waterways regulation—don’t go deep enough. Both pieces spend one too many sentences talking about the lead up to their meeting with their subjects, their trepidation and later relief, which I thought unnecessary. I did, however, enjoy “Dalston Kittiwakes” by Tim Burrows about the parallel fates of Dunbar Castle and the Four Aces club in Dalston, charting their prime through to their ruin.

The perspectives showcased in this anthology seem, however, a little lacking in diversity. The lack of photographs is also unfortunate; a place-based collection would be better complemented with pictures of the places which feature as the mise-en-scene in the stories, perhaps even an illustrated map accompanying the different geographical sections. Still, although I didn’t enjoy all the selections, there were enough pieces I liked to make this anthology worth a read. This is undoubtedly a commendable first collection for a new indie press, and it is good news that Influx plans to publish further site-specific anthologies. I think I’ll bring this book with me as a pseudo-travel guide next time I visit Hackney, follow the looping route Budden and Caless have outlined in their introduction, starting from the Lea Valley then south to the Marshes, on to Hackney Wick and Regent’s Canal and then back up to Dalston and further north to Stoke Newington. As an outsider to everyday Hackney life, it will surely be illuminating for me to put pictures to the names and places.

Published in 2012 in paperback. Thanks to Influx Press for providing a review copy.

Influx has opened up submissions for their next place-based anthology.

Here’s a trailer for the anthology if you want to hear some of the writers read:

[vimeo 36765754]

About Emily Ding

Emily joined Litro in April 2012 as Literary Editor & Web Designer. She made over the website and introduced new developmental and editorial features to strengthen Litro's online presence. She left her position in January 2013, taking a backseat as Contributing Editor to concentrate on writing. She is a freelance journalist with a special interest in travel writing and foreign reporting (with an inclination for Asia and Latin America), and is now based in Malaysia. English is her native language, but she also speaks Mandarin and Spanish, having spent 2007-08 travelling in Central America.