You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingIt’s an exciting time for African science fiction. Since the release of the hugely successful film District 9 in 2009, written and directed by South African Neill Blomkamp and dealing with an alternative Johannesburg where alien refugees are ghettoized, there have been a steady stream of creative projects using sci-fi forms and stories to examine African concerns. Kenyan director Wanuri Kahiu’s post-apocalyptic short Pumzi gained enough attention to get her slated as writer and director of the upcoming Who Fears Death?, described as ‘Lord of the Rings in Africa’.

With several more high-profile African sci-fi films in production, and writers like Lauren Beukes and Nneki Okorafor leading the way in literature, the spotlight is very much turned towards imagined African futures. In 2012, both Bristol’s Arnolfini gallery and London’s Southbank Centre held exhibitions and events exploring the explosion of sci-fi in African literature and film.

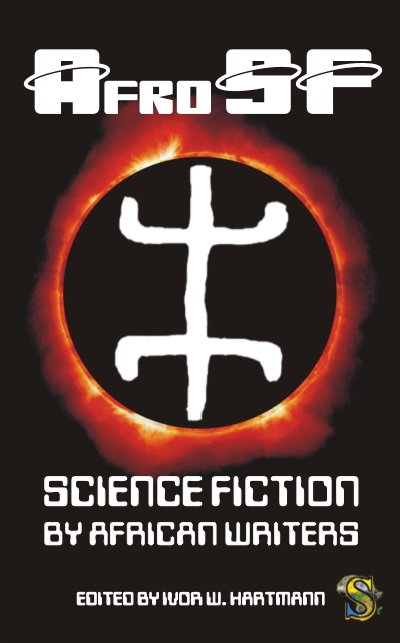

So it’s perfect timing for the release of StoryTime’s AfroSF: Science Fiction by African Writers, a short story collection edited by Zimbabwean writer and publisher Ivor Hartmann. AfroSF is available initially as an ebook, with proceeds going to fund the production of a print edition further down the line.

Hartmann says in the introduction that his intention was to give African writers a forum to make their voices heard, in a genre that allows them to imagine their own futures: “If you can’t see and relay an understandable vision of the future, your future will be co-opted by someone else’s vision, one that will not necessarily have your best interests at heart.” It’s an exciting concept for an anthology, and the result is a collection of varied voices, some powerful and accomplished, not just imagining futures but also addressing the present through storytelling.

The collection opens with a story by Nneki Okorafor, who won a World Fantasy Award in 2011 for her novel Who Fears Death. Moom is a beautiful story, written from the point of view of a swordfish in the polluted seas off Nigera, experiencing the arrival of a transformative alien craft rising from the depths.

Of course, as with all science fiction, it’s not so much the future that’s being dissected here as the present. The pressing concerns of modern Africa are very much at the surface: the stories play on the themes of segregation, exclusion and power. Sarah Lotz’s Home Affairs examines the inevitability of corruption, even in a state run by apparently incorruptible robots.

In Clifton Gachagua’s To Gaze at the Sun, proud parents wait for manufactured ‘sons’ to arrive at their door, eager to send them off to war to keep up with the neighbours. When a newly arrived son shows unheard-of signs of war trauma, this human attribute disgusts his parents:

The sight of her sleeping son repulsed her, curled up as he was like a soft-boned prehistoric thing, the bed sheets hugging his shoulders. His skin was a little torn, the delicate sphere of his humerus visible, reminding her of innards and the reality of a boy experiencing metabolism. The idea of her Stanis as a system of flesh and blood and nerve endings made her nauseous.

There are stories that draw on African ancestral beliefs and customs: Nick Wood’s wonderful Azania follows a group of settlers arriving on a hostile alien planet aboard a ship presided over by a computer that is more like a mother-goddess:

I manage the corridor with my left hand braced against the wall, following etched tendril roots, past the men’s door and on into the heart of our Base, where She sits. Or squats—her heavy casing hides her Quantum core, scored with bright geometric Sotho art—her flickering holographic face above the casing is now the usual generic wise elder woman, grandmother of all. She straddles the centre of the circular room, like a Spider vibrating the Info-Web.

The African imagery, names and language are refreshingly different for the genre, and the idea of settlers carrying mythology and belief from the cradle of civilisation towards the beginning of a new world is a memorable one.

There are also very original stories. Sally-Ann Murray’s Terms and Conditions Apply holds back on the exposition, creating a convincing, if confusing, future of sexual relations objectified to the point where they are part of the machinery of big pharma research. Some of the best sci-fi is like a glimpse into a different world — we don’t need to understand its every custom and detail, we just need to be excited by its possibilities.

There are echoes of Ray Bradbury in Liam Kruger’s Closing Time, a clever and satisfying story about a man who travels to his own future every time he gets drunk, and finds that his future self is taking an original form of revenge.

For fans of science fiction for its own sake, familiar themes pop up: nanotechnology in Efe Okogu’s interesting Proposition 23, where humans are so intimately connected to the future web that the punishment for criminals is to be disconnected, leading to death.

There are gritty, urban near-futures in Ashley Jacob’s New Mzansi, where a criminal underworld revolves around HIV drugs; and Tade Thompson’s Notes from Gethsemane, where rival gangs clash in a future Lagos.

There’s some solid stories in here, although some feel like sci-fi tropes simply relocated to Africa. S.A. Partridge’s Planet X is an understated and enjoyable story in the tradition of the film The Day the Earth Stood Still, asking how we’d react to the arrival of aliens on Earth, in this case in South Africa.

Some of the contributions lack strong narratives – Ivor Hartman has said elsewhere that his approach to selecting the stories for this anthology was to go for solid ideas over quality of prose. This shows in several of the stories, where an interesting concept is unfortunately let down by weak execution, unnecessary exposition or unconvincing dialogue. It’s a shame, as in a collection of this length, slower stories can lose the attention of the reader. But as Hartman makes clear, this anthology is hopefully the beginnings of something much bigger to come, and to that end there’s something to be said for a bag of interesting ideas, even if some are stronger than others, some better written than others. It’s an enticing start.

When we read science fiction we want to be transported. This collection takes us much further than Africa, to a multitude of possible futures: some cautionary, some frightening, some hopeful, all worth listening to.

AfroSF: Science Fiction by African Writers is currently available as an ebook. Buy it here.

Thanks to Ivor Hartman for the review copy.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.