You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

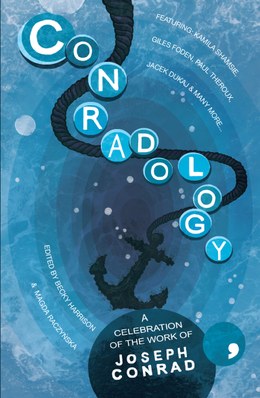

Go shoppingThe author who would become known internationally as Joseph Conrad was born in 1857 in northern Ukraine, a region home to a significant community of ethnic Poles. Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski was born into the land-owning class, to parents who were committed Polish nationalists and dissidents. Both parents died while he was still a child. At the age of sixteen, the young Conrad left Poland for Marseille, where he began his life in the merchant navy. This career, spent first on French and later British ships, would take him all over the world – from the Caribbean to Borneo, India to the Congo – and expose him to the global politics of commerce and capitalism. The novels and short stories which made him famous (among them Heart of Darkness, Nostromo and The Secret Agent) drew vividly from these experiences. Conrad is recognised as one of the earliest and most prominent western writers to engage with globalisation and colonialism: forces which, in various guises, have exerted an ever-greater influence over more and more of the world’s peoples since Conrad’s day. Other themes in his work – terrorism, high finance and political intrigue, as well as psychology – continue to resonate in the present era. Comma Press has now brought out Conradology, an anthology of ten new short stories and three essays inspired by Conrad’s legacy. The book contains much insightful and exciting work, but is thwarted by crucial omissions.

A major pleasure of the anthology is the inclusion of some genuinely page-turning fiction. Kamila Shamsie’s impressive satire “A Game of Chess” is the tale of a rivalry between two high-ranking British officials: the Home Secretary and Police Commissioner, the latter “a child of working-class migrants… [who] was feted by a certain segment of those who had inherited their own privileges and were therefore deeply invested in the idea that rewards came to those who deserved them”. At either side of the action stand identical twins Yousuf and Nasser Ismail, former Guantanamo inmates wrongly accused of terrorism, and now each adopted by opposing factors in the establishment. The story has a novelistic scope, drawing together political machination and terror with personal dramas of ideology and hypocrisy, set on the treacherous terrain of the modern British class system. It is all too believable.

Giles Foden’s “The Double Man” is another gripping narrative with, like many of the stories here, a mystery at its heart. It is narrated by Marisa, an incomer from Madeira and now receptionist in an unremarkable London hotel. Marisa spends much of her time gazing out of the basement window at the passing feet above, a suitable metaphor both for her position in the story and in the wider world, as time and events move onward out of her view. But she is a close observer of those around her, and when after an act of vandalism at the hotel she notices “an expression of panic” cross the face of the normally assured concierge, “as if his self-possession had crumbled”, she is drawn into danger. If Marisa’s voice occasionally jars – her wise, poetic tone sometimes a little heavily applied – the story still manages both to be the affecting tale of a woman’s self-realisation, and a thriller.

Sarah Schofield’s “Expectant Management” is a rarity in this anthology in that it deals principally with internal drama. Jess has taken up a demanding new job, and is disguising a failed pregnancy. These two pressures – her determination not to show weakness, and her unrelieved grief – bear down together, distorting her grip on reality. It’s a work of emotional depth, and a reminder that inner worlds can be as difficult to navigate as any foreign waters.

There is an international flavour to the anthology, which includes several contributions by Polish authors, but the absence of any black African voices – despite numerous direct references and allusions to Africa – is a significant omission. Chinua Achebe’s criticism of Heart of Darkness is well-known[1], but disconcertingly glossed over here. Robert Hampson’s introduction mentions the debate only fleetingly, stating that Achebe “criticised the American academy’s teaching of Heart of Darkness, which foregrounded psychology and downplayed its themes of colonialism and the book’s representation of race”. Achebe said rather more than that; he argued that Conrad depicted Africa as “the antithesis of … civilization”, and dehumanised Africans. The essence of Heart of Darkness, according to Achebe, was a profound fear of the common humanity between black Africans and white Europeans. A counter-view might be that this fear was really a recognition of the hubris at the core of the imperial project. A book such as Conradology, which aims to celebrate the work and impact of Conrad, needs to respond more boldly to the challenge of this debate.

Instead, there are two short stories set in Africa which are ill-judged in various ways. “The Helper of Cattle”, by Farah Ahamed, follows the exploits of Dr Patel, a businessman intent on securing “The Lodge” – a Kenyan safari resort – for his company’s portfolio. Patel is escorted around by Ole, a serious local whose lectures on culture and wildlife are laden with ominous undertones. Ole explains that the Maasai “don’t hesitate when it comes to protecting our land and traditions,” just as the wildebeest, “like many of us … prefer to stick to their own.” Patel meets Ole’s sister, Jamba, who – on top of being a witch – is both cursed and mad. “She pointed her beaded club… and yelled. She moved closer, hissing at him through the gaps in her teeth.” Shortly afterwards, Patel develops a fever. Possibly the story is supposed to poke fun at stereotypes: there is some suggestion that “the Maasai” are deliberately trying to spook Patel (preferring a potential Somali investor). But Patel is utterly insensitive and far from spooked. After his encounter with Jamba, he writes in his notebook: “Maasai women are volatile. Recruiting female staff could be problematic.” He refuses to accept that his fever is caused by a spell. If Patel is the butt of the joke, he never notices, and it remains unclear to the end what the joke really is: has Patel fallen prey to malevolent tribal magic, or hasn’t he? And why, exactly, are we considering that question?

“Mamas” by Grażyna Plebanek is set in an unspecified African country recovering from civil war. The country is now suffering from a shortage of men; the government is dominated by young women, who propose “importing” men to correct the imbalance. Two older women, Mama Fatoumata and Mama Scholastica, have a better idea: they want to reintroduce polygamy. The “Mamas” are simple women; when one of them uses a word with more than two syllables, she has to say it slowly. “Eth-nic-ity. What a word!” The young women in Parliament are “pro-gress-ive”, independent and in possession of iPhones, but when it comes to the vote on polygamy, they are outwitted by the Mamas in preposterously idiotic fashion. As in “The Helper of Cattle”, the premise seems bizarre and the characters irredeemably foolish; I can’t imagine that an insult is intended, but I struggle to understand the point being made.

The idea behind Conradology is a good one. Conrad’s themes remain prescient and wide-ranging, loaded both with dramatic potential and real moral urgency. What can contemporary writers take from an author who was there at the beginning of modern globalisation, and what can they add? The essays bring a different stimulus, including a difficult but original exploration by Jacek Dukaj into the transference of perspective and experience in Heart of Darkness as a precursor to twenty-first century virtual reality and “cultural capitalism”. There are other enjoyable stories here besides those I’ve mentioned; the anthology has left me curious to read more Conrad, as well as to seek out work by some of the contributors. It has, however, also left me with concerns about what has and has not been learnt from decades of post-colonial theory and debate. By failing to engage adequately with the world beyond Europe, or with the arguments voiced by Achebe, the book upholds a one-sided view of globalisation and the colonial legacy.

Conradology is published by Comma Press.

[1] Achebe, C. 1977. ‘An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness’. https://polonistyka.amu.edu.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/259954/Chinua-Achebe,-An-Image-of-Africa.-Racism-in-Conrads-Heart-of-Darkness.pdf

About Anna Lewis

Anna Lewis is the author of three poetry collections. Her latest pamphlet, A White Year, is published by Maquette. Recent short stories have appeared in New Welsh Review, The Interpreter's House, and on Litro.