You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping What is so striking about Teju Cole’s fiction is his ability to end his books with a sense of heavy emotional languor and stark finality. The final chapter of Every Day is for the Thief begins with the narrator considering the difference between labyrinths and mazes: labyrinths contain a meaningful centre, whilst mazes confuse and mislead. It is this demarcation that runs through Cole’s almost psychogeographical novels: is urban space a meaningless maze or a labyrinth with a meaningful kernel to be discovered? If Lagos is the ghost that haunts Cole’s first novel Open City, then it is the protagonist in Every Day is for the Thief.

What is so striking about Teju Cole’s fiction is his ability to end his books with a sense of heavy emotional languor and stark finality. The final chapter of Every Day is for the Thief begins with the narrator considering the difference between labyrinths and mazes: labyrinths contain a meaningful centre, whilst mazes confuse and mislead. It is this demarcation that runs through Cole’s almost psychogeographical novels: is urban space a meaningless maze or a labyrinth with a meaningful kernel to be discovered? If Lagos is the ghost that haunts Cole’s first novel Open City, then it is the protagonist in Every Day is for the Thief.

Open City centres on Lagos-born Julius and his meandering walks through New York, following his growing alienation from both his built environment and the expat community. Cole’s childhood in Lagos is delicately sewn into the narrative of Open City through memories and stories, like his touching recollection of sneaking a bottle of ice cold Coke from the fridge on a hot day. But there is always distance – a clear demarcation between then and now, there and here.

It is what I have dreaded: a direct run-in with graft. I have mentally rehearsed a reaction for a possible encounter with such corruption at the airport in Lagos. But to walk in off a New York street and face a brazen demand for a bribe: that is a shock I am ill-prepared for.

This book, however, focusses much more heavily on the Nigeria of Cole’s childhood (the death of his Father and the fracturing of his relationship with his Mother) and the reality of modern Nigeria and all its contradictions, both politically and religiously. The unnamed narrator pities writers such as John Updike: “who have to ply their trade from sleepy American suburbs, writing divorce scenes symbolized by the very slow washing of dishes”; having watched a fight between two men of a Lagosian highway, remarking that “life hangs out here”.

When the narrator is ill, frustrated by power cuts and the loud hum of generators, Cole’s slow and unhurried exposition gets across the particularly oppressive feeling that Lagos imprints upon its inhabitants – and it is in these passages that we feel Lagos as maze. But on another occasion, when he pursues a woman he sees on a bus with a Michael Ondaatje book, it runs with precision and momentum – the city revealing itself as a labyrinth, with some glimmer of meaning at its heart.

The kernel of Every Day is for the Thief is a very conflicted heart, between Lagos as an integral centre of the narrator’s existence, and something from which he has been detached. Or, more pithily, struggle and absence.

What if everything that is to happen has already happened, and only the consequences are playing themselves out?

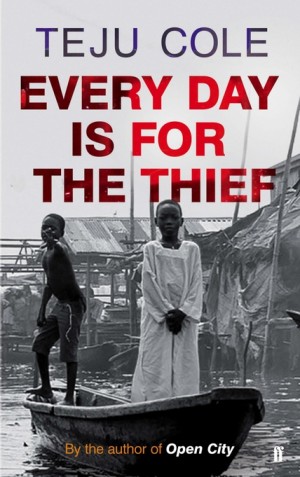

There are inevitable comparisons to be made with W.G. Sebald in tone and mood, particularly in the inclusion of uncaptioned black and white photos that are dotted throughout the book. The reader is left to make up their own mind about what they mean and why he has chosen to include them. Cole started out as a photographer, and the way his narrator surveys his surroundings in both his novels nod to the detachment a photographer feels between themselves and their subject, keeping them at lens length.

It is tempting to read Every Day is for the Thief as the prelude to Open City and to see the narrator as Julius, who has moved to New York and become very successful in his field. But what does this mean then for the narrator’s authenticity, as someone who has experienced Lagos and left? This contradiction is unsettled and becomes transposed onto the reader and leaves the question of who’s past do we reflect on, the narrator’s or Nigeria itself? Surely, we cannot expect a nation’s rhythm and complexities to be solved by one author, and Cole’s accounts are contributing in the same “way a small segment of a coastline is formed with the same logic that makes the shape of the continental shelf.”

About Jonny Keyworth

Jonny is a writer based in Edinburgh, with an interest in African current affairs and culture, having studied a Masters in African Politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies; and is currently working on continuing the research he began at SOAS and also working on a novel based on his experiences in Africa.