You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

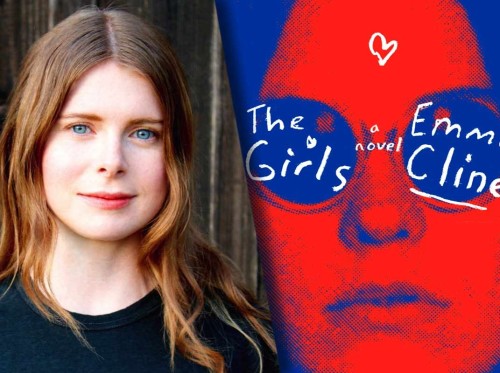

Being a teenage girl is complex, hellish and cripplingly difficult, as is capturing these gruelling years in writing. But Emma Cline does it with aplomb in her startlingly perceptive debut The Girls. It is the story of 14 year old Evie Boyd, a distinctly “average girl”, and her hazy summer of discovery and recklessness in late ’60s California where she gets herself caught up in a cult loosely based on the infamous Charles Manson family. Cline writes with uncomfortable accuracy the complex inner life of a teenage girl and offers an insightful commentary about how they are objectified by patriarchal society and the men that control it.

We first meet Evie four decades after that summer; middle aged and alone after a string of failed relationships and crashing at her old friends Dan’s deserted house. She is interrupted by his 21 year old son Julian and extremely young girlfriend Sasha who recognize her name in association with Russell Hadrick’s Manson-like cult. Answering their questions and observing Julian and Sasha’s dominant/submissive relationship causes Evie to reflect on parallels of the abuse of male power that shaped her teenage years, her experience in the cult and relationship between her father and mother.

The stifling “endless, formless summer” of 1969 serves as a backdrop to Evie’s teenage angst and Cline perfectly captures the restlessness of being a girl on the cusp of adulthood with a desperate need for acceptance and adventure. Evie is an only child, her parents are recently divorced; her mother a New Age convert and neglectful of her daughter due to her father having run off with a much younger woman. Evie spends the first part of her summer performing the mind numbing monotonous rituals of teenage girlhood that society expects of her with her friend Connie (reading frivolous self-improvement magazines, flirting with and fantasising about Connie’s older brother) and experimenting with the first thrills of masturbation. She is off to her mother’s alma mater boarding school in the autumn, and it seems what the future holds for Evie and what society expects of her is a tedious transformation into becoming as desperate and weak as her mother. It is unsurprising then, when her mother gets a new boyfriend and she falls out with Connie, Evie is desperate for love and becomes enraptured by a group of girls in the park. Led by the beguiling Suzanne, these girls are everything late 60’s society forbid teenage from being; sexual, provocative, daring. They are the antithesis of everything Evie has read in Connie’s magazines; the girls are dirty, uncaring and not dressed for male pleasure. They are not unwilling recipients of the male gaze, but have an unwavering gaze of their own. Evie is captivated by their ‘suggestion of otherworldiness’ and sees them as her key to escaping the monotonous world she is trapped in.

Thus begins Evie’s summer at the commune, a remote ranch led by middle aged washed up musician Russell Hadrick and his harem of “thin, harried girls with partial college degrees and neglectful parents”. Russell’s ranch represents everything that society and their parents have failed the girls at, and allows them to be”‘part of [an] amorphous group, believing love could come from any direction”. Evie is an outsider to the group, and drawn in by Suzanne’s magnetism she gives herself willingly and desperately. But Suzanne and the girls aren’t as carefree and autonomous as Evie naively thought. They are devoted to serving Russell, an “expert in female sadness” who targets teenage girls vulnerability and low self-worth to easily overpower and manipulate. To please Suzanne, Evie must also give herself to Russell, first her money and then her body, until eventually he pimps her out to his famous friend in an attempt to get a record deal. Things turn sour when Russell doesn’t get what he wants, leading to the murders alluded to throughout the narrative, of which Evie is not involved, but of which she fantasises frequently about what she would have been capable of if she had been there.

The Manson-esque murder plot is the least compelling aspect of The Girls and is eclipsed by the evocative story of Evie’s coming of age from innocence to experience. Adult Evie’s hindsight analyses the vulnerability of teenage girls and how gender binaries structured her teenage life. Despite being wealthy, educated and part of high society, Evie knows through experience that a teenage girl is the most powerless position in a patriarchal world. She muses; ‘At that age, I was, first and foremost, a thing to be judged, and that shifted the power in every interaction onto the other person.’ Adult Evie sees her theory in place in the character of Sasha, Julian’s teenage girlfriend, whose vulnerability and desperation to be loved is taken advantage by Julian and his friend who bully her into showing them her breasts against her will, much to the anger of Evie. She bitterly summarises this objectification in her own childhood observation of gender stereotypes: “That was part of being a girl – you were resigned to whatever feedback you’d get. If you got mad, you were crazy, and if you didn’t react, you were a bitch. The only thing you could do was smile from the corner they’d backed you into. Implicate yourself in the joke even if the joke was always on you.”

It is at home where Evie first notices the dominant/submissive gender binary at play, where the “joke” was always on her mother. Evie’s mother is cast as the weak submissive woman, who chooses to live in knowledge of her husband adultery. Once he leavers her, she becomes a desperate middle-aged divorcee in need of another man in order to fix her. In doing so she neglects her child and falls into the arms of Frank who she hopes will fill her void of self worth, but who Evie can see is just using her too. Evie witnesses her weakness and bitterly despises her mother for it, and Cline brilliantly captures her bitter teenage angst: “The only person left to hate was my mother; who’d let it happen, who’d been as soft and malleable as dough. Handing money over, cooking dinner every night, and no wonder my father wanted something else.”

Yet, Evie ends up echoing her mother’s submissiveness in the commune with her relationship with Russell. In defying her mother by stealing her money for Russell, performing sexual acts when he orders and obeying his commands, she becomes the gender role she is rebelling against, acting under a false consciousness that patriarchy entrenches. Russell preys on the teenage girls lack of self worth, leading them to believe performing sexual acts with him is making them more beautiful and accepted as part of the group. Evie says of her experience with Russell ‘I was eager for our encounters, eager to cement my place as one of them’ showing how easy it is for a teenage girl to be taken advantage of. Their desperation to be accepted by their peers, to be an object of love makes them submit so easily to older men like Russell. Adult Evie reflects on this, saying: “Poor girls. The world fattens them on the promise of love. How badly they need it.”

It is through the character of Tamar, Evie’s father’s younger girlfriend, that Evie sees an anomaly in her gender role and sees the possibility of a life beyond the ranch. Evie equates Tamar as closer in age to her than her father, and they form a sisterly bond that replaces Suzanne when Evie is sent to live with them as a punishment from her mother. Tamar has Evie’s respect, because unlike her mother Tamar has “outside opinions” and compares her exciting life not conforming to her gender role “like a TV show about summer”. Evie bitterly notices similarities between Tamar and her mother in the way they made consolations ‘making the world mirror my fathers wants’ but unlike Suzanne who is completely in the thrall of Russell, Tamar is not submissive to Evie’s father. Evie witnesses Tamar “dismantling” of him, enabling Evie to be less intimidated by him and in extension all men, reducing him to “just a normal man”. Cline uses Tamar leaving Evie’s father as a message of hope for Evie, that with age and experience she doesn’t have to conform to society’s patriarchal gender roles.

Cline uses the image of Sasha leaving with Julian at the end of the novel to emphasise that the abuse of teenage girls’ vulnerability is as relevant today as it was the four decades previously during Evie’s summer at the ranch. But Cline also ends on a positive note, by cleverly subverting the gender binaries that construct the novel in the closing paragraphs. Evie says of the eventual arrests of the cult; “even at the end the girls had been stronger than Russell”, projecting a powerful message that girls’ inner strength is not to be underestimated. The novel ends with Evie now grown up, using her own strength that she has gained through her journey and experiences, echoing the same way she realised she was no longer intimidated by her father as a child. She recognizes that the man walking towards her on the beach is not a figure to be feared or that will harm her, but “just a normal man” and that she is powerless to him no more. A poignant end to an insightful and incredibly relevant novel.

About Hayley Camis

Hayley Camis is Litro Magazine’s #TuesdayTales reader. She is a graduate from the University of St Andrews where she read English Literature and spent a year studying American Literature at The College of William and Mary in Virginia. She now works at Little, Brown Book Group in their publicity team.