You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

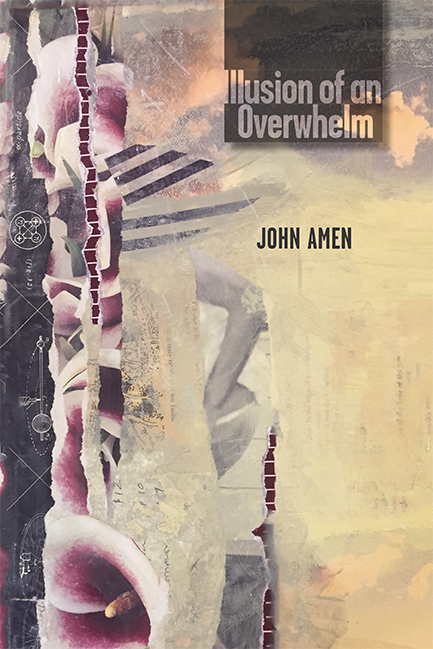

Like the folk tradition that John Amen springs from, Illusion of an Overwhelm incorporates multiple registers including Americanisms, text speak and emojis, but the dominating patter is that of a metaphysical poet exploring the confusion and disorientation of contemporary existence through bodies and all their messiness. Constituting four series, Amen’s fifth collection is one that whirs with anxiety as it distils contemporary American life into several unanswerable questions. But even the act of posing these questions allows for the creation of bridges, albeit unsteady ones, which build toward comprehension. Whether or not we should cross these bridges is another issue, as there is little to be reassured by in these pieces except for the darkest of dark wit, which is often present in the language and that feels like worked dough until it produces something light.

In the first series, ‘Hallelujah Anima’, the reader is plunged into accounts of desire – both physical and metaphorical – and a journey towards self-understanding accompanied by Anima, a woman who alludes, goads and reassures. She is an intimate and yet often detached part of the narrator’s psyche as he attempts to evaluate his place in the world, amongst the wealth and worth of its structures. ‘Desire’s what you desire,’ he writes in ‘10’. ‘You think you chase satiety, instead driven deeper into cravings that circle themselves’, suggesting that this will be an endless search for satisfaction if satisfaction is what is sought. Anima, a near-constant presence in these poems, ‘sits naked in the brown lawn, smirking’ (in ‘16’), knowing, perhaps, that she is both the solution and a contributor to this endlessness. Charles Simic-like prose sits alongside free verse in this section, the combination of which adds to a free-flowing movement of themes and ideas.

‘The American Myths’ takes a more structured approach, with eighteen poems each consisting of three six-line-long stanzas, but with sestina-like repetitions of images and objects that again push language and understanding to its ends. The effect of this is no more locating for the reader as we are placed directly into the swirling middle of an exploration of the intersections of economics, politics, race and religion in contemporary America. Super PACs and roods loom over a white father, a dead mother and a black son; prescription medication numbs reality ineffectually; ‘Jacksons’ (twenty-dollar notes) flutter and burn; uncomfortable examinations rise up as voices shift perspective. All of this is drawn out within a frame which seeks to acknowledge a kind of impotency in the face of conflict. From ‘5’:

The game seems winnable when I’m alone,

the hundred filibusters trailing in to silence,

each vagary a direct line to the empire.

Grease & sugar are the gateways to God,

but solitude’s the cosmic nipple. I’m numb

to the wheel, numb to my dear white dad.

A host of different characters appear in ‘My Gallery Days’, the third series, which reflects on art, making and a creative life. This section marks a shift towards poems that have a slightly more narrative bent, reading memoir-like at times as each piece explores the drivers of this particular experience of the art world in New York. There is a perpetual search for funding and grants; squats and shared living spaces in noisy urban spaces abound. Drug abuse weaves in and out of relationships between a cast of characters who form a kind of soundtrack to this period as artists and critics create, discuss, score, argue and in some cases, die. Notions of legacy seem to be at work here, with lines from ‘23’ tying together, once more, the lack of any kind of permanency in life: ‘We fled ourselves / for a season, clutching our self-portraits, / we were ghosts long before we knew it’.

Finally, the shortest series, ‘Portrait of Us’, examines a relationship, shifting once again this time to a more domestic space of a shared life and towards a more literal language to consider intimacy and what occurs to these ideas when a relationship changes or ends:

Every room itches with your story,

days lost & sinking like a weighted body

into some cold, stygian trough –

so many faces irretrievable, voices irretrievable.

It’s in this final section that Amen reaches towards a particularly compelling notion, sieving away the layers of performance that are rife in the previous sections, by considering the act of remembering itself rather than the actors:

People say we rejoin the eternal body,

make a beeline homeward, but what good is this

without knowing, without memory?

Can life be said to exist

that can’t reflect upon itself?

Illusion is a demanding collection because it insists on querying anything we might be sure of, and worthy of rereading if just to simply let the language of these pieces move and morph towards each new appreciation as it appears.

Illusion of an Overwhelm is published by NYQ Books.

About Laura Tansley

Laura Tansley's writing has appeared in Butcher's Dog, Cosmonaut's Avenue, Lighthouse, New Writing Scotland, PANK, The Rialto and is forthcoming in Stand, Tears in the Fence and Southword. She is also co-editor of the collection 'Writing Creative Non-Fiction: Determining the Form'. She lives and works in Glasgow.