You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

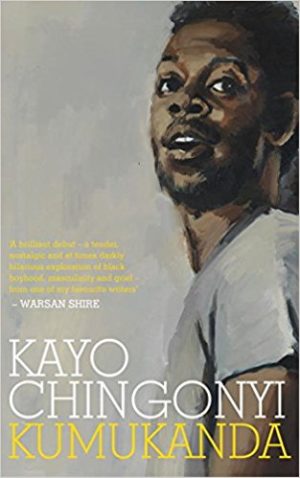

Go shopping The author’s note at the start of Kayo Chingonyi’s full-length debut states: “Meaning ‘initiation’, kumukanda is a ritual that marks the passage into adulthood of Luvale, Chokwe, Luchazi and Mbundi boys, from North Western Zambia and its surrounding regions.” In this collection of poetry Chingonyi is exploring rites that mark the movements of boy to man. Having moved to the UK at the age of six and missing this particular initiation, Chingonyi’s poems consider what other places of self-reckoning should or could be for a black British man feeling distanced from the traditions that form a particular part of his identity.

The author’s note at the start of Kayo Chingonyi’s full-length debut states: “Meaning ‘initiation’, kumukanda is a ritual that marks the passage into adulthood of Luvale, Chokwe, Luchazi and Mbundi boys, from North Western Zambia and its surrounding regions.” In this collection of poetry Chingonyi is exploring rites that mark the movements of boy to man. Having moved to the UK at the age of six and missing this particular initiation, Chingonyi’s poems consider what other places of self-reckoning should or could be for a black British man feeling distanced from the traditions that form a particular part of his identity.

The beating heart of these poems is music, not least because of the poet’s own cross-genre creative output and a song’s uncanny ability to situate the reader immediately in a memory. In ‘Winter Song’: “When Snowman starts up, I’m back there, / in the arctic north of boyhood, lost / in the moment just before the bass drops.” There are enough clues in these poems to create a Kumukanda playlist of Vogue-able New York Garage from the 1980s, to the inescapable juggernaut of millennial Eminem to infectious 2step, white-label Wiley tracks and Grime. I found myself Googling away at these references, discovering wee musical gems but knowing all the while it could never recreate the experience of hearing these songs for the first time or having to work hard to find them. Because for Chingonyi it’s not just the music, but all the trappings of the ’90s and new discoveries: the TDK tapes, the walkman and hovering over the pause button to make a seamless mixtape recording from the radio. ‘Self Portrait as a Garage Emcee’ charts this adolescent journey, where music becomes a distraction from the lingerie section of the Littlewood’s catalogue in favour of the Sanyo cassette player bought part-exchange from Tandy, blasting “R&B on E numbers, hi-hats the hiss / of hydraulic pistons, snares like tins dropped / on tiled floors”. All of this harking back to a time when to gather musical knowledge was a challenge, as opposed to simply queuing it up on a Spotify playlist. Patience was required and so the rewards were bigger. But to suggest these recollections fall simply into a catalogue of nostalgia is to ignore the imposed limits and borders often present in this poem. The music Chingonyi loves can only be indulged in before his mother is back from work, before the teacher on duty in the playground rounds the corner. Seeking something unimportant to record over, an absent father’s voice is found amongst his mother’s tapes. The Slim Shady LP ruins everything because rap becomes a white man’s American accent that Chingonyi has to adjust to when previously being able to spit lyrics was the only thing that could allow school boy cries of “nig nog” to “bounce off my back”. Music not only transports, it becomes a place to connect memories with a developing sense of self and all the beauty and pain that comes along with this journey.

There is a rough chronology at work in Kumukanda. Poems move from school days to university days to working days, particularly in the movement calling a spade a spade, a powerful, nine-poem exploration of institutional and culturally-ingrained racism. Language and attitudes lacking in nuance are nestled deeply in those ‘safe’, purportedly liberal spaces of sport, education and the arts where talent is supposedly the only thing that matters but which are, in reality, encased by uncomplicated or even uninterested understandings of black experiences. The effect of limits when learning are clear. In ‘On Reading Colloquy in Black Rock’, a seminar tutor’s anxieties steers a class away from a frank discussion on the appearance of the ‘N-word’ in Lowell’s poem in favour of the broader context, “Ours is to note the working mind behind the word”. And in this line which recalls the Light Brigade, a pattern of light and darkness emerges across this movement and the experience of the weight of these words on Chingonyi. This movement also considers Chingonyi’s experience of theatre and acting, covering his experience at a conservatoire and then auditioning for parts. But it is poetry, rather than acting, that becomes an expressive outlet for a voice (rather than the voice) which is able to address a self that is still becoming, unlike acting which seems to force Chingonyi into a shape that doesn’t fit. In ‘Casting’ his agent encourages him to become more two-dimensional, but for someone who has a talent “for rakes and fops” being asked to use his “street voice” to form a shape of stereotypical British blackness is not good enough.

As the collection continues relationships develop until the ultimate moment and maker of an adult, the death of a parent. First a father in ‘Alternate Take’, a “charismatic spectre” who even in absence is an influence; then a mother in ‘A Proud Blemish’, which refers to the caesarean scar which she bears, “rippled with ridges from weight loss” that sets alarm bells ringing till the music of a mother tongue creates for Chingonyi a “discord of two / languages” which “keeps me from the truth I won’t hear”. In ‘Orphan Song’ death becomes a flight home to, this reader imagines, the birthplace of parents and the site of one part of an origin story; an endless journey back and back and back again through generations of genes. These and all the other moments across this collection form a pathway of identity-establishing practices through what could be understood as the auto/biography of a young, black British man.

London and its estuary reaches are particularly prominent in this collection, but the Tyne and even Loch Long are also present, all connected by water and its constant merging and dividing; an apt metaphor for dual identity and these poems explore the ways the shallow pools of a person can be made full, as well as how the tide of a person’s home country ebbs and flows within them, overwhelming in some instances, then almost absent in others. In ‘Baltic Mill’ these watery pathways become a person’s history: “The exact course that brought / us here is unimportant. It is that we met / like this river, drawn from two sources, / offered up our flaws, our sedimental selves”.

At thirty, there is a youthfulness to Chingonyi’s poems which is not typical. It isn’t necessarily that boundless energy we’ve come to associate with young folk, but a tirelessness I sense in this work. Reading his poetry, identity becomes something spongy, something whose form has not yet solidified as it soaks up and draws us in to this process of growing. In some instances it is something quite soft, layered, impressionable and at times incredibly delicate, like his own slow-blinking performances which can be found on YouTube, the rhythms of which ripple their way this work. But like the music that is so much a part of this collection, these rhythms build, creating an unmistakable, actualising power.

Kumukanda is published by Vintage.

About Laura Tansley

Laura Tansley's writing has appeared in Butcher's Dog, Cosmonaut's Avenue, Lighthouse, New Writing Scotland, PANK, The Rialto and is forthcoming in Stand, Tears in the Fence and Southword. She is also co-editor of the collection 'Writing Creative Non-Fiction: Determining the Form'. She lives and works in Glasgow.

One comment