You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping “The first thing and last thing I do everyday is see what strangers are saying about me. I pull the laptop closer…”

“The first thing and last thing I do everyday is see what strangers are saying about me. I pull the laptop closer…”

Kitab Balasubramanyam can’t get out of bed or go to sleep without reconfirming his own existence in the cloud – because Kitab (meaning “book” in Hindi, Punjabi and Urdu) is a cyborg. He’s the main character of a novel entitled Meatspace, for crying out loud; he exists in a nightmarish world, our world, imprisoned not only by the digital screen but also the first technology, language.

“The more friends and followers you have, the more interactions your create. It’s all about interactions.”

Kitab’s life is banal and depressing. Sure, he’s got a novel out, but that just isn’t doing it for him. He gets drunk at home with his brother, discusses women with his single father, and laments his break up with Rachel. His nemesis is a collection of uneaten chutney in his kitchen. He flits between the Internet and the pub, finding pleasure in neither. A modern human, then.

”You did,” she says, shaking her head. “You gave up on real life.”

“I was just trying to make a name for myself.”

“Yeah, but at the expense of everyone around you. In real life…”

“Meatspace,” I say to myself.

Fundamentally, Nikesh Shukla’s entertaining second novel is a diatribe against the dehumanising binaries of the physical and virtual worlds – what on earth is real when you can travel not only through time but also space via a smartphone whilst sitting on your arse in a pub? Meatspace’s pursuit of a synthesis between these worlds is unrelenting and dark; a superficial lightness of tone eventually gives way to the dark underbelly of reality.

Shukla is clearly in control of his work and what the novel lacks in stylistic flair it makes up with carefully observed humour. Meatspace’s jokes hit harder because they come as emotional relief from the dysphoria. It’s funnier, even, than Shukla’s debut, Coconut Unlimited, in the way that the second album from your favourite punk band at first sounds a little too serious (Where have all the hooks gone?) but nevertheless marks their most assured and accomplished work to date.

“Google destroyed the journey, man. All you have to do is look him up on Facebook and boom, journey over.”

Meatspace’s dedication to capturing the zeitgeist is not necessarily the stuff of compulsive fiction (how, the novel asks, can you tell a story when the ending can be summoned up in seconds?), yet Shukla mines the vast catalogue of connection without consequence with the incessant misery of a particularly tiresome accountant who has discovered a talent for the deadpan over his morning porridge and becomes the next Jack Dee. Stick with it, though, because Meatspace’s humour lies beside these liminal, often miserable, places.

“Kitab, I’m going to stop you there, and let you know: we just spent a quarter of a million dollars redeveloping our site … for a chewier click-through matrix full of snackable content. In terms of the ideation and its agility in the marketplace, I suppose, yes, that is a nifty grey…”

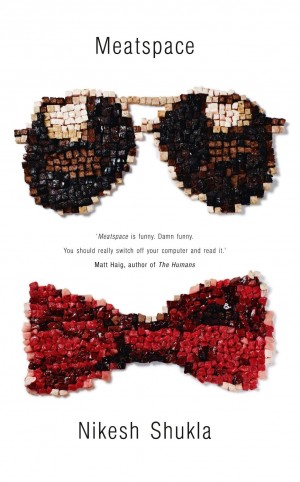

Characters feel dislodged from the world with the endless pursuit of connectivity replacing actual connection, but Shukla differentiates himself from his contemporaries by plumbing the depths of disconnection rather than simply documenting it. The Internet bleeds into real life: Aziz gets a tattoo of a bowtie under his neck (“It’s a proper dinner party tattoo. He looks like a clown on his day off”) and goes off to New York in search of his doppelganger; Kitab’s namesake tracks him down in London. Hilarity, most certainly, ensues.

“Kitab 2 has become analogue … We share a moment next to the urinal while a man farts audibly in the cubicle.”

Shukla’s prose is robust and bold but primarily comes to life in dialogue. Kitab and his brother, Aziz, yap along with the joyful bonhomie of the sharpest double-acts, while Kitab’s world-weary father often steals the show. No one is perfect, but they’re not perfectly terrible either.

There are rare occasions where the novel wanders into banality. Conversations, for example, about social media feel a little too like a paint-by-numbers exercise at times and those unwilling to participate with Shukla’s world may be put off by all the chiaroscuro. There’s also the ending, which is signposted with a beautiful touch, but smacks of the familiar on arrival.

“Connections used to be important. Now the very meaning of the word, it doesn’t mean shit. Associations have some weird cultural capital now.”

Ultimately, Meatspace should be commended for capturing a moment in time without feeling tired before it reaches the eBook. Most novels – if not all novels – avoid the Internet and its dehumanising powers because we simply lack the language to describe it. Meatspace goes someway to filling that void in our lexicon by taking a tattoo pen right to our flesh. A troubling, disturbing second novel that may not hit the inner bullseye of the great Here-and-Now dartboard, but is certainly a damn-sight closer than most.

About David Whelan

David Whelan is a fiction writer and journalist based in London, England. He was formally Litro's Reviews Editor and Fleeting Magazine's Interviews Editor. Currently, he writes for Vice's food vertical, Munchies. He is one of Untitled Books's "New Voices" and his fiction has also appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Shortfire Press and Gutter Magazine, among others. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from UEA.