You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping“No one claims to be an expert in novels who only reads novels in Portuguese, or Tagalog. And so the history of literature necessarily exists through translation. The reader who wants to investigate the difficult art of the novel will end up with a whole warehouse of imported goods.”

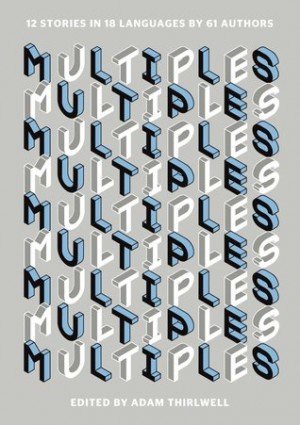

Adam Thirlwell, from the introduction

How do you read an experiment? If this were a science article, I’d turn to different kinds of documentation: the reports, the plans and the results. But what if this experiment is a collection of stories: simultaneously the attempt and its outcome? Multiples is nothing short of a grand experiment in storytelling; authorial rebellion; language, and how to read a book. Talking about it, let alone reviewing it, turns out to require some experimentation of its own.

Approach:

Novelist Adam Thirlwell began with twelve stories, originally written in almost as many different languages. Each of these was given to a writer who translated it into English. Their translation was then given to yet another writer, who translated it again to their own language. It does sound complicated, and yet, after the initial shock of glancing at the intricate list of contents, you very quickly understand the logic, and very soon you are absorbed in the game.

It’s an adventure in which each individual player is perhaps more lost than you are as a reader. Each story becomes a series of tales, which not only transport the plot from language to language, but also document the struggles each writer has had to face. These include some of the most internationally applauded names of today – Zadie Smith, A.S. Byatt, Dave Eggers – as well as lesser known ones. Many of them aren’t even close to fluent in the languages they are translating from, and most of them are first and foremost fiction writers, not translators. On top of this, there’s the fact that none of the originals are included in Multiples: the first text you encounter is itself a translation. This triple removal from translating as a profession is crucial, as it reveals the wildly different attitudes it is possible to adopt, while still calling what you do a “translation”.

“For me, writing is ultimate freedom, because you don’t need to take anyone else into account when you write; you can just be yourself. But as a translator, I felt the exact opposite: every time I’ve touched the keyboard, there was this dead Czech guy breathing down my neck.”

Etgar Keret

Method:

For some, loyalty to the original is essential. The smallest word choices are closely considered, one option weighed against the other. The changing of “slob” to “beggar” is dwelt on for days. However, the jumps – the creative blips – soon begin to surface. In the first English version of Enrique Vila-Matas “Los de Abajo”, there is no beggar at all. Only untied shoe laces. Loyal to their own style, writers begin to add things, manipulate and change. A story in Hungarian appears first in German prose, then turns into verse in English. “Los de Abajo”, once it has become “People Underground” in Tom McCarthy’s version, has been divided into numbered sections. By the time “A preface to writing samples”, Clancy Martin’s version of Kierkegaard’s Danish text, has become “Översättarens anmärkning” by Swedish novelist Jonas Hassan Khemiri, it bears no resemblance to the original. Instead of the Danish philosopher’s satire on the writing life, Khemiri delivers a fictional letter from an affronted translator to his publisher.

The term “translating” has different elasticity in the eyes of different writers. A.S. Byatt refrained from rewriting a kiss because she “didn’t have the right” to, whereas Adam Foulds produces a set of short reflections in which the original plot can be followed only if you are looking for it: “both a rendering and a reading” of the same story. Icelandic Sjón asked his thirteen-year-old son to memorize the story and then wrote it down. Experiments give birth to more experiment.s The idea of “staying true” to an original also implies some sense of responsibility, but to whom? When translating what he’d been told was a story by Kafka, Israeli author Etgar Keret went as far as convincing Nathan Englander to keep the word “animal” instead of “creature”: “This way we both got a better final text in the end, and Kafka’s ghost will haunt Nathan and not me.” Some of the most entertaining sections of Multiples are the “Notes on Translation” ending each series, when the “players” of Thirlwell’s game are asked to comment on their process: their small agonies, their choice not to use Google translate, or to use it throughout. It’s clear they had fun.

Results:

What of the stories as entertainment? How do you read one story three or four times and stay interested? Multiples highlights the subjectivity of all our reading experiences. What’s available to me as a Spanish, Swedish and English speaker is different from what a friend who speaks German and English can read of the collection. Most intriguing of all is perhaps how I slowly am taken in by the book’s spirit of playful rebellion. Trying to follow the transformation, I find myself wishing for more and more change: I begin to root for the irreverent. Perhaps it’s because as a fiction reader I am not trained to read stories in multiples, or because variety is entertaining. Chloe Hooper calls it “bio-translation”, a term I like. It brings to mind a cluster of cells changing, a body mutating in all its aspects.

How do you read such a book? You might have to read it multiple times. I’ll come back to it when in need of a little creative and linguistic revelry. With only three percent of books sold in the UK being translations, it is a very important one.

“My first thought on reading “Umberto Buti” was that the protagonist seemed strangely Chinese, with his rejection of politics, aversion to risk, sense of inferiority, and thwarted desires. I asked myself: if he’d been born in China in 1931, how many details of his story woul have to altered?”

Ma Jian

Multiples was published in August 2013. Buy it from Forbes.

About Jessica Johannesson Gaitán

Jessica Johannesson Gaitán's short fiction and poems have appeared in publications such as The Stinging Fly, Gutter, Structo and The Scotsman. One of her stories was a winner in the Glimmer Train Open Fiction contest in the autumn of 2016. Originally from Sweden and Colombia, she arrived in Bath via Edinburgh, where she works as a bookseller and podcast editor. She is one half of @therookbookery