You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

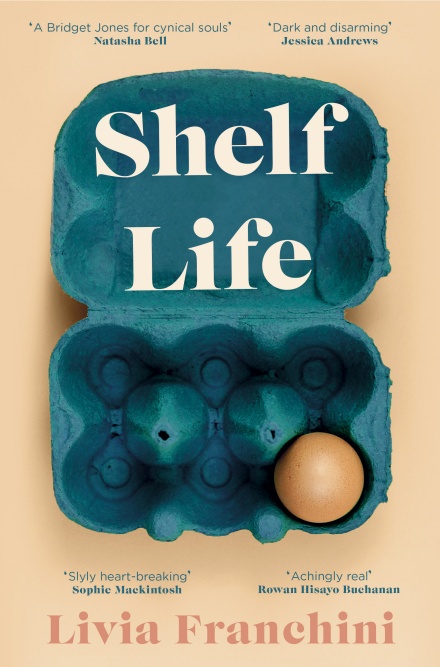

Livia Franchini’s Shelf Life is bookended by shopping lists. Both written by Ruth, a thirty-year-old nurse working in a care home. The first comes shortly after Neil, her partner of ten years, abruptly terminates the relationship, to “share his love with more than one person”. In the midst of the break-up, Ruth is charged with organising a hen party for her frenemy Alana, who within hours of Ruth’s split, announces her wedding.

Starting with Eggs, each item on the list provides a clue as to what went wrong with the relationship, from its inception in Rome to its demise in a dimly lit west-facing kitchen in England. In Tampons, we learn Ruth was regarded as an outsider by teenage schoolfriends. In Sugar, we follow Ruth and Neil’s first meeting. Whole Chicken turns to Ruth’s relationship with her mother, played out over a truly bizarre chicken supper, where not a morsel is consumed. Spanning ten years of the relationship, the list jumps between the distant and close past, switching perspectives from Ruth to Neil to Alana, interspersed by random email exchanges, sent by the predatory Cumulonimbus to women on his sexual radar.

Franchini is a poet and translator, with the originality and skills to whip up lives from the unremarkable and commonplace. Eggs begins with a lovely contemplation on the nature of weight: “Here are some things I know about weight. A pound of feathers weighs as much as a pound of bricks, but a pound of bricks is easier to carry.” She has a keen ear for the vernacular. And, at her best, is inventive, observant and lyrical: “These days, sleeping feels like a kind of drunkenness, like travelling at sea.” However, while there’s lots to admire in Shelf Life, its main character, Ruth, is frustratingly unsatisfying: who she is, what she loves and hates, her reasons for starting a relationship with Neil, let alone remaining in it, remain obscure. This may be a deliberate Deleuzian ploy – a take on identity which suggests personality is formed through experiences and differences; thus, the reader is never intended to “know” Ruth, as none of us can truly be “known”. But literature is not life. And what this means on the page is that we simply don’t know enough about Ruth to care. Paradoxically, Neil, for all his toxic, sexually aggressive behaviour, likely to have the #MeToo Gen shuddering in their sleep, offers a clearer semblance of motive and character. And we are left in no doubt as to why he has too much love for one person.

The final shopping list in the book is by far the most interesting. The devil is always in the detail, and it’s the detail that arouses our curiosity. This list is proof of Ruth’s recovered self, her identity, now sharply etched in: Yellow Tail Pinot Grigio, Aussie Miracle Cure and Heinz Tomato Soup. Reading this list, it’s impossible not to think of the late, great sociologist, Erving Goffman, who said: Show me what newspaper a man reads and I’ll tell you where he lives, how he decorates his front room and how he makes love to his wife.

A character who’s forged from the neutral labels of wine or pudding is always going to be a harder challenge than one who can easily be known through her choice of flavours, brands, and market positioning. Or, as Goffman might say: Show me a woman with a bottle of Yellow Tail and 2 Gu Chocolate Puddings and I’ll tell you whyher relationship started, endured and finally faltered.

Shelf Life is out now in paperback from Penguin.

About Christina Sanders

Chris Sanders has been writing short stories for over ten years. She has been published in: Writing Women, Quality Women’s Fiction, Peninsular and TQF. In 2011 she won an Arts Council bursary to appraise her first novel, and has contributed to various Arts Council writing projects. At present she is working to complete a collection of short stories on the theme of ‘Compromise.’ Chris Sanders holds a Masters in Education, and is currently working with women from BME communities in Hastings to use storytelling as a way to explore identity and heritage.