You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

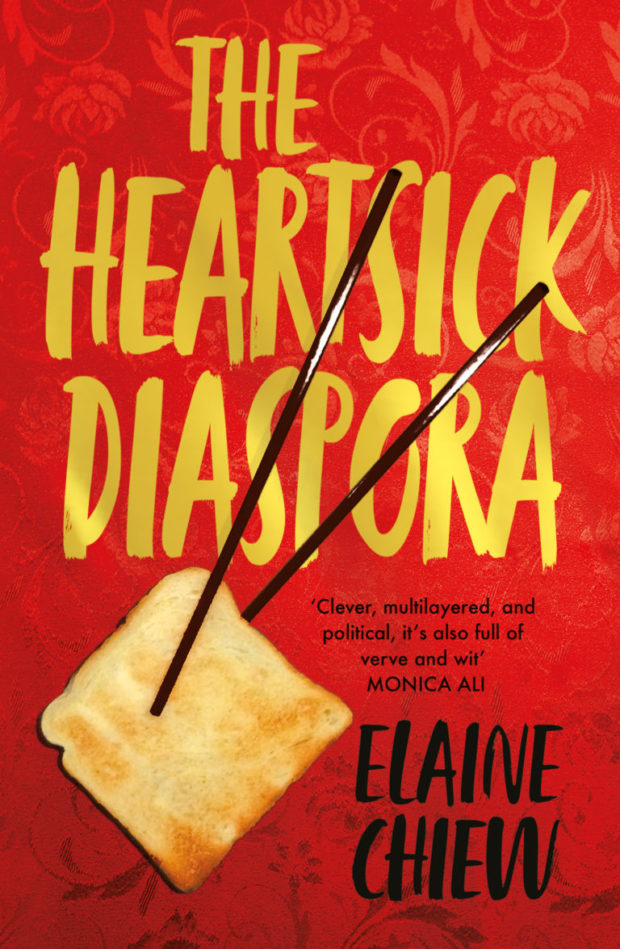

Elaine Chiew is ethnic Chinese from Malaysia; she was educated in the USA and then moved to the UK. She is currently living in Singapore. Her debut collection of short stories reflects this background. The stories examine the lives of the Malaysian and Singaporean Chinese diaspora across the USA, Britain, and internationally. These are doubly hyphenated identities: the immigrant children of a Chinese community that established itself in the Straits Settlements in the early twentieth century. At one point a character’s mother visiting from Singapore is impressed by London’s Chinatown. “It’s just like China!” Her daughter wryly remarks, “Although she’d never been to China.”

The diversity of voices across the collection reflects not only Chiew’s talent, but perhaps also the long span of years over which they were written. The earliest published piece won the Bridport International Prize in 2008, a feat nicely bookended by the title story winning Second Prize a full decade later in 2018. Her work has appeared in several anthologies and in Unthology 10. She edited the anthology Cooked Up: Food Fiction from Around the World, and this familiarity with food culture makes more than a cameo appearance in this collection.

Chiew writes with equal facility and insight from the perspective of the older generation of immigrants who never became proficient in English, and the younger, college graduates and professionals, whose comprehension of the Chinese vernacular is increasingly sketchy. In the drama-filled “Run of the Molars”, a mother arrives from Singapore to visit her three daughters in London. It’s a recipe for much concealing of secrets, putting up with whining, and unsolicited moral judgements. The reader need know nothing of Chinese culture to appreciate the sheer passive-aggressive contrariness of a mother who, when served platters of (London) Chinese food by her daughters, narrows her mouth and asks for two slices of white bread. All the repressed family dynamics seethe to the surface in this story of great heart and sardonic observation of cultural differences.

Lily is portrayed as the most progressive of the three daughters. Her sister, despite at one point referring to the mother as a “hillbilly”, launches a caustic attack on Lily for becoming too westernised: “Why do we have to talk about everything? You’re so fierce westernised, just because you’ve married an ang moh. Put you on a couch, Freudy-dreudy, this solves everything, eh?”

In this piece as with several others, food is metonymic for fidelity to one’s heritage.

In the mythology-warping satire “Confessions of an Irresolute Ethnic Writer”, the writer-narrator gazes in the mirror examining his zits and trying to descry his true face: Model-Minority face, Fresh-Off-The-Boat face, Charlie Chan face. A little later he ponders over whether it is ever permissible to use the description “nice sloe eyes”, even in jest. The farcical tribulations of our Ethnic Writer should serve as a caution not to read these stories too reductively as explorations of ethnic identity. They are stories of family bonds and friendships and struggles to establish one’s place in the world. Often a wry distance is maintained from the characters, allowing space for the reader to revise their opinion and see the larger picture.

This authorial skill of allowing room for differing perspectives comes to the fore in “Friends of the Kookaburra”. Sansan receives a surprise call from an old college friend, the Madonna-idolising Irene, seeking to renew contact. Twelve years before they had been “thick as thieves”, done voluntary work together, camped out cramming for exams. But they grew apart: Irene began to hang out with the more popular students. “Irene’s wild talk, throwing around buzzwords like ‘sectarian politics’, ‘cultural hegemony’, ‘power dialectic’.” Fast-forward the years, and this friend comes across as effusive and presumptuous. Given the nature (and title) of the book, the reader may be disposed to sympathise with the Malaysian-Chinese Sansan. It’s a finely balanced portrayal, but we begin to warm to Irene’s brash frankness. “Her eyes scan Sansan’s face for residual historic friendship.” The vexing and elusive question intrudes nevertheless: is the tension between these old friends a clash of Western individualism with Confucian values, or is it a personality clash?

Irene turns the tables in a dramatic fashion – no spoilers here. If the modern short story is frequently charged with a lack of narrative and contrived subtle endings, Chiew is never guilty of this.

“Chronicles of a Culinary Poseur” is a comedy, verging on tragicomedy, about the Chinese owner/chef of La Lumière – a French restaurant in Manhattan. Due to a sequence of events involving a lethally bilious food blogger and the local loan-shark goons, Kara finds herself pretending the vacuous, Grecian-god-looking Bernard is the executive chef. It’s a role Bernard takes on with panache and a splash of cologne (in the kitchen!). This might not be the outstanding story of the collection, but it shows the range of Chiew’s voices. Another story gives us a would-be “tiger mother” trying to integrate with the other fearsome moms hot-housing their kids through an intimidating prep school. In a nod to Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, this mother composes extempore rap, not hymns, to express what she dare not speak aloud.

The title story is meticulously structured and a deserving winner of the Bridport Prize, but it’s in “Chinese Almanac” that Chiew pulls out all the stops. The writing here buzzes with just the right amount of confusion. Fragmented syntax, untranslated Chinese characters, and unexpected bawdiness depict, and replicate in the reader, the feeling of joining the festive table of the extended family of one’s new girlfriend/boyfriend. The necessity for slapstick should rightfully trump any writer’s notions of keeping the writing restrained. Manboobs, dildoes, death, and Jesus all find their way into the dinner-table conversation. When the egg foo young lands on the floor and the meal comes to an abrupt end, the daughter hesitantly asks her bashful beau if he would like to visit again. “He gives an emphatic nod.”

The writing is exquisitely precise. The narrator’s father, a mathematics graduate who came to America and always worked at menial jobs, is now going through a process of estrangement from his wife. In a sentence to make any writer envious, the son describes the attempt at flirting with the middle-aged Korean woman who runs the drycleaners: “I watch this interaction with a portion of incredulity, a portion of amusement, a portion of ineffable catch-in-my-throat.”

A recurring theme is the dual nature of family bonds, on the one hand supportive and on the other hand they can be stifling. On the whole such bonds come out positively, even in the case where a young man hides his sexuality from his parents. “There’s a hierarchy of sins: being gay is not as heinous as being unfilial,” he says.

A calmly optimistic humanist view of human nature informs the fictions. An immigrant in dire straits steals twenty dollars from the cash register only to replace it the next day. The revelation that an uncle sought to have sex with a transsexual is regarded as a perplexing disorder of the libido. A mother whips her piteous, ghost-haunted son and the ensuing scandal forces her to publicly apologise to him. A Confucian worldview, perhaps, but Chiew has already cautioned us against seeing characters as determined by their ethnicities.

Chiew also works as a visual arts researcher. She has written elsewhere of being attentive in her fiction to the potential and meanings of objects, events, and dialogue, and to their linkages and echoes off each other. As well as food, a chamber pot or dialect phrase can become a recurring motif and resonate with meaning.

Three of the stories are historical fiction, written in a more classic style of prose. These stories, for this reader, seem to show that the generational divide rivals that of the east-west cultural divide, though this may not have been the writer’s intention.

Geopolitical realities are changing rapidly. Singaporeans are now the sixth richest people in the world. The world of Amy Tan’s novels is gone. Chiew’s characters are university students (fees for international students are notoriously high), accounts managers, restaurant owners, insurance underwriters – global nomads as one character says. In two stories they are low-wage workers. “The Chinese Nanny” is perhaps the sole story where ethnicity feels like a limitation to be overcome. It’s a good story, though without that feeling of entanglement the others induce, where the reader is unsure where to commit their sympathies.

In a collection with such a range of themes and styles, there’s going to be something that’s not to the reader’s taste. For me it was the mythological parody “Confessions of an Irresolute Ethnic Writer”, which hardly deserved so many pages, clocking in at the second longest.

These stories do what short fiction does best: point a light at lives rarely given voice, and depict dramatic situations which involve and vex the reader.

The Heartsick Diaspora is published by Myriad and Penguin SEA.

About Aiden O'Reilly

I am originally from Dublin, and graduated in mathematics. I abandoned a PhD in complex dynamical systems. Later I lived 9 years abroad, in London, then Berlin, and later in Poland. I have worked at many different jobs to earn money. My short fiction has appeared in Prairie Schooner, the Dublin Review, the Stinging Fly, the Irish Times, and many anthologies and literary magazines – a total of 29 stories. I review books for the Irish Times, the Dublin Review of Books and other places.