You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

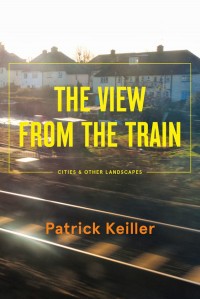

Patrick Keiller’s film London (1994) has haunted and intrigued me since I first saw it nearly five years ago. The film, a blend of documentary and fiction, presents a year in London as seen through the eyes of an imaginary protagonist, Robinson, whose thoughts and insights are related by an unnamed narrator. Keiller, through Robinson, seeks to examine London, suggesting that it “no longer exists” – that it is the “first metropolis to disappear”. This heightened awareness of absence is central to Keiller’s relationship with the urban landscape of London, as well as the critical impetus behind much of his filmmaking. It is still there, at the heart of his latest book, The View from the Train, a collection of essays published by Verso that charts Keiller’s writing from the start of his career in the late 1970s to the present day. Although his more recent films, Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010), have moved away from London, this collection of essays is clearly devoted to the landscape of the city in which he has been immersed for the best part of forty years.

In his introduction, Keiller sets out the influence that surrealism has had on his interpretation of London, in particular the exhibition Dada and Surrealism Reviewed at the Hayward Gallery in 1978. Surrealism, since the work of André Breton, has been symbolically embedded in the landscape of Paris, but Keiller saw how easily it could be applied to London, by imagining the capital as what Roger Cardinal termed the “soluble city”. This notion of the “soluble city”, in a constant state of flux and revision, is present in much writing about London, such as Jonathan Raban’s semi-fictional Soft City (1974), and greatly influenced Keiller’s filmmaking. At a recent talk about his work around Battersea and Nine Elms at the Open University, he returned to this idea, suggesting that, while continually changing, in some ways London hasn’t really changed at all. In his early work, Keiller documented the architectural changes of the 70s and the rapid cycle of ‘new’ architectures in the era of late capitalism. His work has often recapitulated the city as having an organic – rather than controlled or wholly planned – evolution. It is clear in this career-spanning collection, possibly with the virtue of hindsight, that Keiller considers continuous change to be in some way the status quo. He does not mourn for a lost London, but takes pleasure in re-appropriating what has been overlooked.

In one essay in this collection, Popular Science, Keiller quotes Guillaume Apollinaire’s description of the London suburbs from the train as “wounds bleeding in the fog”. Apollinaire stayed in London in 1904 and 1905 and saw the city’s rapid suburban expansion as a flight from the wounds at the city’s heart. Apollinaire’s beautiful phrase seems not just to encompass the suburban ideal that transformed the landscape around London at the turn of the twentieth century, but also to foreshadow the increasingly dystopian London of the 1970s that Keiller came to as a student; a city traumatised by the collapse of the Ronan Point tower block and troubled by the decline of the post-war modernist dream. In his essay Dilapidated Dwellings, which accompanied his television documentary of the same name for Channel 4 (2000), Keiller looks at the legacy of this period by juxtaposing what he calls ‘new’ space – corporate, short-lived – and ‘old’ space – residential, degraded.

In many ways, Keiller’s perspective represents a particularly British mentality; his vision of London embodies a conundrum of town-planning that dates back to the reconstruction of the city after the Great Fire of 1666. Unlike Paris – with vast swathes of its centre straightened out by Georges-Eugène Haussmann in the mid-nineteenth century – London remains a hodgepodge of architectural narratives. Keiller uses the term ‘palimpsest’ in one of his early essays, characterising the city as being continuously rewritten, its land and architectures reused and adapted, rather than as a modernist tabula rasa. Whereas Apollinaire’s view of a bleeding London characterises a city at the turn of the twentieth century, Keiller’s appreciation of Apollinaire typifies a longer view of ebb and flow in the old and the new.

In his essay Benjamin’s Paris, Freud’s Rome: Whose London? (1999), the art writer Adrian Rifkin describes London’s streets as having a “linguistic” structure. Keiller plays with this idea in his own essay Imagining. Like Rifkin, Keiller considers his own history as a London commuter, as well as a wanderer, in a quintessentially psychogeographical manner, although Keiller treats this term with scepticism, lamenting its recent apolitical reincarnation at the hands of certain London writers. And yet, Keiller’s films are clearly part of this re-emergence of psychogeography in London – what Keiller calls “the current tendency”. Will Self has alluded to this in his own review of The View from the Train, in the London Review of Books, saying that the “unplanned perambulations” that make up Robinson’s cinematic narrative, and indeed Keiller’s praxis as a filmmaker, are, as Robinson puts it, “seemingly intent […] on bringing about the collapse of what used to be called neoliberalism”, and are therefore highly political. As Keiller states in the earliest essay published in this collection, The Poetic Experience of Townscape and Landscape:

The desire to transform the world is not uncommon, and there are a numbers of ways of fulfilling it. One of these is by adopting a certain subjectivity, aggressive or passive, deliberately sought or simply the result of the mood, which alters experience of the world and so transforms it.

Despite Keiller’s misgivings about psychogeography (particularly what he sees as its role in gentrification, which he describes as a form of colonialism) his vision and practice align with many of the post-Thatcher, London-based psychogeographers of the 1990s, such as Will Self. In fact, the popularity of his films, and the reason for this collection, lies in his very singular ability to consider and alter one’s experience of urban and rural landscapes in a way that many would associate with psychogeography.

This collection is a mixed bag, but it does have a fragmented charm. A recurring motif in many of his later essays, evoked by the title, The View from the Train, and giving a loose sense of a theme, is the parallel development of cinema and technology, and the coinciding decline of the cinematic panorama with the growth of the railway. In both Film as a Spatial Critique and Phantom Rides: The Railway & Early Film, Keiller returns again and again to Henri Lefebvre’s assertion that the “space of common sense, of knowledge, of social practice” and everyday discourse was “shattered” in around 1910. Evoking Walter Benjamin’s formative essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Keiller looks at the changing dynamic of cinematic narrative, from the early ‘cinema of attractions’ – in which a camera was mounted on the front of a train to create a continuous, single-frame, moving narrative – to the fragmented montage of space and time in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929). He suggests that the train had an important role in early cinema, both as a subject and as a parallel technology that eroded this idea of a shared space, and the boundaries between geographical and mental space.

Like the railway itself, this collection has an intrinsic, almost perverse linearity to it, moving through Keiller’s thinking and work over forty years and charting his changing voice from failed architect to successful filmmaker and academic. It can be repetitious in a way that is alternately illuminating and frustrating, but for fans of Keiller it brings an important critical dimension to the reading of his films and his thinking over the past forty years. In the essay Architectural Cinematography, Keiller does give some details of his filmmaking process, but this is all too short and there is not much said about the making of his later films or his exhibition at Tate Britain in 2010. That said, such omissions do not make The View from the Train anything less than invaluable reading, especially as Keiller’s essays are a singular companion to his films, considering the problems of his work without forcing the reader to reach firm conclusions. In that very postmodern way, they pose questions and reflect on his work without resolution. Keiller may pick holes in his own impact, but this collection solidifies his place in contemporary cinema and highlights the importance of criticality and politics in filmmaking. Here, as in his films, Keiller more than fulfils his own brief, as laid out in the first essay in the collection, “to alter the experience of the world and so transform it”.

The paintings that accompany this piece, by Walter Steggles of the East London Group, feature in From Bow to Bienalle, at the Nunnery May 9th – July 13th 2014.

The View from the Train is available now.

About Bea Moyes

Bea is currently studying for an MRes at the London Consortium, Birkbeck. She is a writer and researcher involved in exploring the poetics and cultural history of urban spaces, with a particular passion for yarnbombing and temporary street installations. Until summer 2012 Bea was director and curator of short stories at the digital publisher Ether Books and has worked with a number of publishers as well as for literary publicists and magazines.