You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

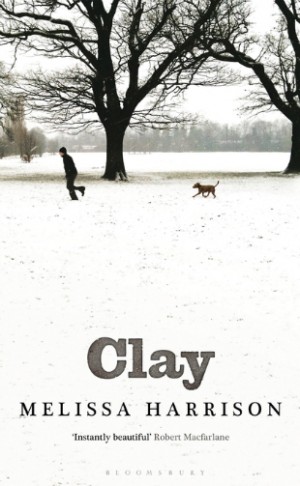

Go shoppingWhat are the borders between the urban and the rural? Between consumerism and conservationism? Between innocence and experience? These are some of the questions concerning Melissa Harrison’s debut novel Clay. In it, a disparate trio are both brought together and separated by their sense of isolation from, and curiosity about, the natural world.

We begin with a prologue, a two-page paean to ‘The little wedge-shaped city park [that] was as unremarkable as a thousand other across the country… despite the changing seasons many of the people who people who lived near it barely even knew it was there’. This little wedge-shaped park is at the centre of the novel. It is an edgeland where Clay‘s characters move and gather, following plotlines that are less linear than seasonal. The chapters are named after pagan holy days, and there are brief eddies and flourishes, moments of growth and decay.

The story proper starts in media res, in a council flat. The police are interviewing eight-year old nature lover TC about his friendship with kind-hearted Polish immigrant Jozef. TC lives with his estranged mother and her half-decent boyfriend, Jamal, while Jozef works in a takeaway and longs for the farm he lost in Poland. He finds solace with TC and their innocent enjoyment of nature. These opening chapters are expositional and slow-moving, the city park quietly teaming, flourishing, growing, dying, living.

Then there’s Sophia, a seventy-eight old widow who lives opposite the wedge of city park. She exchanges letters with her granddaughter, the florally-named Daisy, who despite living less than half a mile away is spiritually and socially distanced from the acre of ‘grimy’ and ‘litter-blown’ common. Despite this, her connection with her grandmother leads her to enjoy the park, where she meets the working-class TC. The suggestion is that the common makes us communal, while the consumerism, ugliness and drab routine of modernity is fundamentally inauthentic.

A great deal of time is devoted to describing the changing of the seasons, the small majesties and intricate dealings that we would see if we only bothered to notice.

The brambles formed a dull, purplish carpet beneath the trees, but at the paths’ margins was the fresh green of the new season’s cow parsley and nettles, still just a few inches tall.

While Harrison is a skillful nature writer, there can be a hard-edged primness to her prose. She lacks the deftness needed to describe her characters in their urban dysphoria with as much fullness and life as she does her closely observed fauna. At times, Clay can lack contrast and drama, the impersonality of the third-person omniscient narrator failing to connect us with the characters.

For all the insistent loveliness of Harrison’s nature, there feels little at stake. We are told as much as shown about these characters. Even the bad guys, TC’s negligent mother and the brutish Denny, are lost in Harrison’s softness and lyricism. Her style doesn’t convey interiority with precision, and I noticed many plot holes. Where has TC’s father been throughout the novel? He simply turns back up at the end. Is the police’s evidence against Jozef credible? I didn’t feel it was. And, my biggest question: if we have lost our innocence and connection to the natural world, can a simple trip down to the local park really sort us all out?

Clay is Harrison’s lyrical attempt to make us notice. It is a modern fable designed to show us what happens when we lose our innocence, yet Harrison’s construction of her nature-loving characters have too palpable a design upon the reader. Having everybody getting off on nature all the time can be grating. I began to wonder whether a belief in the consolation of nature is actually just another bourgeois myth. Is there really more authenticity in the soul of the world, the hushed breathing of the acacias, the belief in our elemental bond with nature?

Nevertheless, despite the simplicities in Harrison’s character motivation and her overly simplistic philosophical distinctions between the layers of real and unreal, Clay does still – almost – connect us to the edgelands, to the urban pastoral, to the earth that made us.

About Wes Brown

Wes Brown is a writer based in London. He is a Co-ordinator at the National Association of Writers in Education, administrator at Magma Poetry and Director of Dead Ink Books. He is currently writing a novel based on the Shannon Matthew's kidnap and training as a professional wrestler for a book about masculinity and storytelling. His debut novel, Shark, was published in 2013.