You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Truth has often proved itself to be slippery. This isn’t my idea – it’s Nietzsche’s: “There are no facts, only interpretations,” he wrote. It’s Borges’: “Historical truth… is not what happened; it is what we judge to have happened.” It’s Larkin’s: “Strange to know nothing, never to be sure/ Of what is true or right or real.” And, of course, it’s Orwell’s. Orwell believed in the truth, certainly: “However much you deny the truth,” he wrote, “the truth goes on existing, as it were, behind your back”. Yet he was all too aware of its slipperiness, the ease with which it is manipulated. In 1944 he determined that the “really frightening thing about totalitarianism is not that it commits ‘atrocities’ but that it attacks the concept of objective truth; it claims to control the past as well as the future”, going on to add that “[h]istory is written by the winners”.

It is this idea which informs Yan Lianke’s disturbing depiction of a labour camp during China’s Great Leap Forward in his Man Booker International Prize shortlisted book, The Four Books. The narrative is pieced together through fragmented passages from the four books in question, the first of which is Heaven’s Child, an anonymous account of the events in this “Re-Education” camp bearing tonal affinities with the Old Testament (“So it came to pass” and “He saw that everything He had created was good” are not untypical pronouncements). Through this curiously biblical language we learn about “the Child”, the naïve overseer of the compound, and the Rightists he is charged with reforming, men and women known only by their occupations – the Author, the Scholar, the Theologian, and so on. The second and third texts are both written by the Author, an especially slippery character, who – in an Orwellian comment on the tussle between subjective and objective truths – is not trusted by the more ethically sound Scholar. Hoping to be rewarded by the Child, the Author agrees to write Criminal Records, a detailed catalogue of his fellow Rightists’ wrong-doings, but alongside this are fragments from his own novel, Old Course, a retelling of the events put down in Criminal Records. The final book, of which we see only a snippet at the end of the narrative, is a philosophical tract entitled A New Myth of Sisyphus, a further testament to Yan’s interest in allegory.

Not only is truth confused for the reader by these conflicting narrative voices (translated by Carlos Rojas with praiseworthy nuance), but it is also repeatedly confused for the characters. Towards the beginning of the book, the characters witness a scene from a play which – in keeping with the novel’s biblical overtones – is reminiscent of Pontius Pilate’s appeal to the crowd at the end of Jesus’ life. The plot “followed a professor who despised his country”, we learn. The actors ask the crowd what should be done with him: ‘“Shoot him!”’, they respond. ‘The crowd laughed, and waved their fists. “Yes, just shoot him!”’ And then, we read, the professor “collapsed like a rag doll. Everyone initially assumed this was merely a performance, but then they saw a pool of blood on the stage”.

Later, a pair of Rightists accused of committing adultery are “paraded through the streets of every Re-Ed district, the spectators repeatedly demanded that they perform the spectacle of their adultery, and would beat them if they refused”. What is real in this context and what is performance? The Author goes on to write that “[h]alf a month earlier, they had been two normal people, but now they bore no resemblance to their former selves”. Here, then, is when the truth is at its most slippery: when a sense of self becomes confused, when former beliefs and personal truths are lost. Is there any truth in being “the Musician” when you can no longer play music? “The Linguist,” we hear, “was the former director of the National Center for Linguistic Research, and had overseen the editing of dictionaries used throughout the country. But he now found himself at a loss for words. He looked at the Scholar’s inquisitive gaze, then silently bowed his head”. The Theologian, desperate for food, “took a portrait of Mother Mary from his pocket… and laid it on the ground, stomping on the figure’s head. He deliberately ground his foot on the portrait’s eye, leaving it a black hole”.

This loss of identity, this Orwellian triumph of an all-consuming system, is at the book’s core. We catch rare glimpses of an alternative truth beyond the Great Leap Forward:

With the Scholar and Musician wearing their dunce caps and placards, which years later would become priceless collectibles, the cart stopped in the entranceway to the district.

This parenthesis hints at a different reality, a time when the paraphernalia of humiliation has become a hangover from the past.

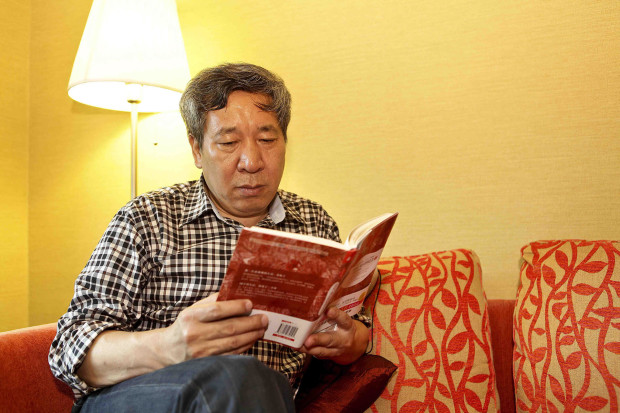

It is interesting, although unsurprising, that a book so laden with confused truths should be written by a writer whose work has shown a constant commitment to honesty. Yan examines the effect of an AIDS epidemic in rural China in his novel Dream of Ding Village, while unflinchingly satirizing the Cultural Revolution in Serve the People!, and, as a result of this subject matter, his fiction has been periodically banned in China. Confirming the importance of creative honesty, he says of The Four Books:

It is an attempt to write recklessly and without any concern for the prospect of getting published. When I say that I have written this recklessly and without concern for publication, I do not mean that I have simply written about mundane or contemptible topics, such as coarse and fine grains, beautiful flowers and full moons, or chicken droppings and dog shit, but rather that I have produced a work exactly as I wanted to.

The novel’s fascinating narrative structure, its ugly events and allegorical characters make for a thought-provoking read, but – above all – it is this honesty of intent that is Yan’s most remarkable achievement.

The Four Books is published by Vintage and is available in paperback for £7.99.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.