You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingFor our Germany theme, Michael Spring inspects three works of fiction that explore the amazing change between the country of the past and present, and forces us to consider whether we too could be culpable of such atrocities.

The world of 80 years ago – in Europe at least – now seems weirdly odd in so many ways as to make the scene seem almost mediaeval. It is hard to think about a world in which Italy should invade Ethiopia, a bitter civil war break out in Spain, France and Germany to be continually confronting a precipice of conflict, and in which, crucially, dictators bestrode the earth. For as coherent a view as you’re likely to find of the events and the history of the time, Elisabeth Wiskeman’s Europe of the Dictators is required reading – a personal narrative of a uniquely dysfunctional period of history, which leaves many readers open-mouthed in astonishment.*

Characteristically, her unsentimental prose allows us not only to see – but also to understand – a period that gives room on its stage to Mussolini, King Alexander and King Zog, and of course, Adolf Hitler.

“In his propaganda, Hitler promised everything to everyone,” she explains. “Now that it is easy to see what he intended, the credulity of his audiences seems difficult to explain.” His strange fascination as an orator, his appeal to primitive mass emotions, “in a country where national arrogance had been followed by humiliation,” were all factors, as was his promise of salvation from decadence.

Some more familiar elements of the view however – financial crisis in Germany, unrest in the Balkans – help to bring us closer to today, but the profound sense of confusion about those times, particularly in Germany, remains. It is all very well after all, for those of us on the “correct” side of the Second World War, to make self-satisfied speculations about ‘character’ or the ‘spirit of the nation’ that enabled us to avoid fascism, but few writers have confronted the issue of whether – and why – Nazi atrocities could have happened here.

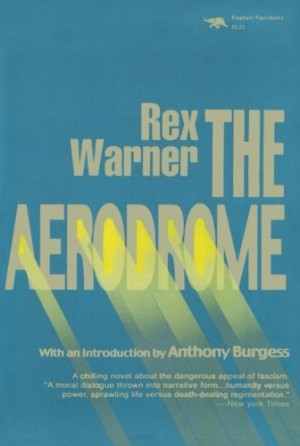

The Aerodrome, Rex Warner’s symbolist masterpiece (published in 1941) stands almost alone in trying to get to grips with the lure of fascism, as a thoroughly degenerate and un-English village confronts the air base established on its outskirts.

“Your purpose,” the Air Vice Marshal explains to his recruits, is “to escape the bondage of time, to obtain mastery of yourselves…We in this force are in the process of becoming, a new and more adequate race of men.” It is the promise of Hitler and all the dictators.

But seen from a German perspective, there are more profound and deeper questions to be answered. Coloured by collective guilt, overshadowed by the vast atrocities, how should individuals respond to both the rise of fascism, and the success of the post-war German economic miracle?

Abish’s How German Is It, a strange but very readable work of fiction, attempts to do just that. Never quite answering all the questions it raises in terms of plot and character, it (in a surprisingly gentle manner) forces us on every page to consider the real question at the heart of the book, was the Holocaust and the Nazi experience something that could only have happened in Germany?

Part mystery thriller, part comedy tour of German society, How German Is It centres around two brothers. Ulrich Hargenau is a writer and the estranged husband of a former urban terrorist. His brother Helmut is a successful architect, building stylish but rickety backdrops for the rich and famous to pose against, as well as statement public buildings that for some reason seem consistently to be chosen as terrorist targets.

The book (published in 1980, when the author was in his late fifties) is set in Wurtemberg (the brothers’ home town) and in Brumholdstein, a fictional new town – and home of the equally fictitious philosopher, Brumhold, “who has enabled us to see ourselves as we truly are” – built on the bulldozed rubble of a concentration camp formerly known as Durst, which itself has been quietly removed from history.

“Durst … has no official history … not that anyone has tried to hide or conceal the fact … but nothing on Durst is on the shelves, since, as the librarian will explain, Durst was by comparison with other concentration camps quite small … quite insignificant …”

Society seems to have quietly collapsed. The mayor is corrupt, the quality of cakes and pastries is a major focus, the men are relentlessly unfaithful to their wives, while the women who appear are strangely compliant to the sexual whims of the males. Everyone clings to the old class distinctions, while terrorist bombs explode, mysterious individuals emerge to take pot shots at the brothers and Franz, the traumatised old servant and Wehrmacht soldier, builds a model of the old Durst concentration camp from matchsticks.

Symbolically then, it is no surprise when a sewer in the main street bursts, releasing a terrible stench and uncovering a mass grave underneath the town.The book’s characters have the same kind of careless jauntiness as The Aerodrome, but without the more explicitly allegorical approach. How German Is It assumes an assured semi-surreal quality in which the characters seem inhabit a similar, but less familiar society to the one we are aware of, underlining the book’s demand that we re-double our focus on what we see.

This is a world where memories are smothered in concrete and collective amnesia.“In this small community, did it really matter what anyone may have done, or failed to do, in the war? If they did anything, it was the predictable.”

The devil’s advocate is everywhere in this book, where there are all too often convenient short-cuts to good and bad – the brothers’ father, for example, is revered as an anti-Nazi hero (shot for his involvement in the Stauffenberg plot) when for many of the war years he was comfortable enough to wear his swastika lapel pin.

In this world, the urban terrorists seem to have captured the moral high ground, even though their crimes are characterised by a pathetic randomness (a bomb in the Post Office, a guard on a waterway persuaded to shoot two policemen and blow up the lock that allows ships into the North Sea).

The terrorists may be emptily destructive, but are they the force that might release those myriad tensions? Is violence the only response to the past, and does the past still live?

When, finally Ulrich Hargenau is hypnotised, “he was positive that he was not a good hypnotic subject,” but, “as he opened his eyes,” he finds “his right hand raised in a stiff salute. ‘I think we’re getting there,’ the doctor said pleasantly.”

‘What is really at stake is one’s image of oneself,’ says the quote which prefaces the novel. The questions we are left to answer at the end include: when should the past become scenery? When, if ever, can the mistakes of past society be ignored? And what kind of image of the future do we have? Those questions may have become less urgent with the passage of time. They are though, questions that every generation needs to answer for itself.

*Elisabeth Wiskeman was born in England, though of distantly German descent. She worked throughout the war for British Intelligence in Switzerland, and was responsible for at least one act which, temporarily at least, halted the Jewish deportations from Hungary. Knowing it would be passed to Hungarian intelligence, she deliberately sent an unencrypted telegram to the Foreign Office in London that contained the addresses of the offices and homes of those in the Hungarian government who were best positioned to halt the deportations and suggesting that they should be targeted. In subsequent nights, an air attack that went wrong resulted in some key government buildings being destroyed. It is thought that this caused the authorities to suspend deportations.

About Michael Spring

Michael Spring lives and works in London, a city that never ceases to provide inspiration of one kind or another. He works for a graphic design agency now, but has been a director of a PR firm, and an award-winning advertising copywriter. He is @dudley_antipope on Twitter.

For our Literature Feature @LitroMagazine, Michael Spring inspects Germany’s burden of history: https://t.co/UBDwFUD4sq

3 books that might help you get your head around Germany and Fascism at #Litro https://t.co/DanDHuKiFH

if you are lover of the online games to play the more games in the this website more user are like this website games thanks for this post .https://theyahtzee.com a big collection of the games.