You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

“I am among those who think that science has great beauty,” Marie Curie said in 1933, in one of her many timeless examples to fill the testament of the purest form of love for science she left us. “A scientist in his laboratory,” she argued in favour of her job, and vocation, “is not a mere technician: he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairy tales.”

More than half a century later, her statement still holds value and truth. With Janna Levin – American astrophysicist and writer – the universe is modelled into the space of modern fairy tales. In “Black Hole Blues and Other Songs from Outer Space,” Levin finely chronicles the arduous thus all the more fascinating and rewarding story of the detection of gravitational waves – spatial undulations, as waves in a cosmic sea, the curling and ringing energetic result of the impact of some of the densest astrophysical objects in space. As she patiently recomposes the pieces of this puzzle of great discovery of science, its mechanism dismantled at length, she unveils from the start the mastery of a poetical language that inhabits even the most rational-oriented thought:

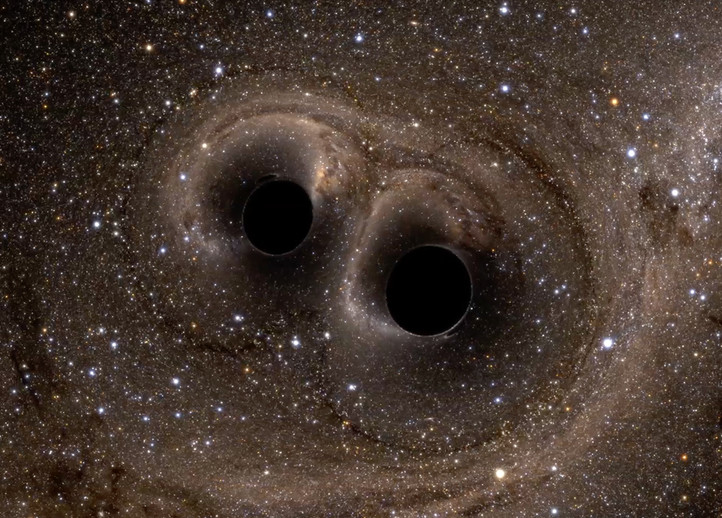

“Somewhere in the universe two black holes collide – as heavy as stars, as small as cities, literally black (the complete absence of light) holes (empty hollows). (…) An astronaut floating nearby would see nothing. But the space she occupied would ring, deforming her, squeezing then stretching. If close enough, her auditory mechanism could vibrate in response. She would hear the wave. In empty darkness, she could hear space-time ring.”

A collision of a pair of similar dragging forces is the most powerful event since the universe originated (can you envision the power of a billion Suns released a trillion times and more?) In this process, energy and sound are like two sides of the same coin: the energy output in the space-time geometry translates into the noise carried off in gravitational form. Such a loud impact, Levin clarifies, we can’t perceive naturally if not for a “material medium,” something that works as our ears to any sound, a vehicle to record and bring back to us audibly those faraway space ripples. Levin simplifies, “much alike a wave on a string of an electric guitar can be converted to sound with a conventional amplifier.”

This is what LIGO – the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory – has been created for. The instrument, a masterpiece of the most brilliant effort of thought and labour, is a set of complex mechanisms bound for an essential reason for being: the recording of the skies to seize the ring of chaotic masses, “Lilliputian modulations” of the cosmological mayhem.

The book is, then, a contemporary tale set between earth and space. As much as Levin’s narrative is a precise reportage of scientific accomplishment, it is nonetheless an account of the lives behind it; the astrologist honours the human facet of science by always giving men a seat next to purely theoretical concepts. All her esteem is pointed towards the “Troika”, the curious triad at the foundation of LIGO: Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Ronald Drever. As their stories intersect, we understand that they belong to elastic minds and hearts to the core, pioneering thinkers able to host great ideas as well as great hope, to nurture a challenging dream in an often-demanding reality without ever questioning its worth. Through them, Levin opens a window on the scientific world for us to see how tenaciousness and faith are twisted together as the fundamental fuel of this progressive endeavour.

Under her acute lenses, each scientist is captured in a personal synthesis. Rai Weiss’ is “high fidelity”. His whole destiny dotted with musical signals, he had one life ambition “to make music easier to hear.” Add to this purpose some sentimental parenthesis of unlucky outcome – to conquer a pianist’s heart by learning to play piano – to glimpse the perfect premise for an intangible yet by then mind-fed LIGO archetype. In Plywood Palace, the legendary engine for genius and creativity at MIT headquarters, the first elementary interferometer was born as a Gedanken problem, an experiment of the mind in Rai’s relativity course – “it looked like it wasn’t nuts to do that,” Rai explains.

He was playing with the incognito, just like a couple of others liked to do too. Collectively or individually, the Troika took action by embracing the shared credo of ‘science for science’s sake.’ Gravitational waves were a novelty, unaccredited for many and convincing just for few. To bring to completion the project didn’t imply to succeed in making it of some use: in the spirit of the arduous, continuous confrontation between natural forces and humans’ obstinacy to understand them, something had to exist out there first, to make its detection happen.

For Kip Thorne, brilliant astrophysicist but above all unshakeable believer, a detection was a matter of time. He had always trusted the mysterious abundance of the universe and decided that its wonders could have been better explored by pointing an ear, where Galileo had once pointed a telescope, to the skies.

In the “golden age of relativity,” Kip and Rai started it all. With their own map of the universe at hand, they looked for promising natural resources and only stopped in front of the faintest of forces: gravity.

When, in 1979, a reticent Ron Drever entered the scene, Kip and Rai finally had their own “scientific Mozart,” a frugal Scottish inventor who left Glasgow for Pasadena jealous of his genius. Ron possessed the singular craft of a rational and together instinctive way of thinking and giving shape to marvellous things out of nothing. Or better, anything: “random bits of rubber tubing, sealing wax, scraps from previous experiments” found endless possibilities of a second life under the belief that, whenever useful, everything could be valuable; “he had nothing and he could make something admirable of it,” is Levin’s punctually apropos remark on him.

With the unknown as a matter of study, Rai, Ron and Kip stood admiringly at the foot of a mountain that they showed no hesitation in wanting to climb. Levin subtly traces a common thread of all the similarities that drew them together despite their substantial differences: a healthy dose of unconsciousness and optimism, with equal parts naiveté and hazardousness. To this positive temerity of theirs Einstein anachronistically had an exact explanation, which also served to draw, back then, their perfect portrait: “If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?”

Serendipity also belonged to their destiny. If ever they knew what they were looking for, they could never foresee the surprising things they would have faced while looking for something else. With each of the observatories – two full-scale concretions of a dream – conflicts inevitably anticipated satisfactions. The campaign teetered between fickle billion-worth dealings with the NSF and a scientific community of belittling wagers and thumbs-down mixed with the diffidence of a provincial pettiness (the Louisiana LIGO, it was believed, could make you travel in time). But, despite all, Kip continued spreading his peaceful wisdom around, Rai his legendary walks in the depths of the machines and Ron the genial instinct with which he kept unravelling the knot of the most rigorous calculations with disarming simplicity.

“Black Hole Blues” is, to some extent, a big, beautiful lesson in faith; a diffused sense of it stands out above all the rest. Einstein wrote about general relativity knowing little of the future of his studies in the years to come just as much as Levin couldn’t predict that a wave was on its way to the earth while she was writing about it, to meet the deadline of the centenary of his theories. What was it that pushed them both forward?

On the frenetic run towards LIGO, a pinnacle of scientific excellence at this moment of time, many protagonists were lost. Joe Weber, the trailblazing explorer of the skies too ahead of his time, was the first of them. He had seen “Evidence for Gravitational Waves,” as his paper stated. As an experimentalist, though, his plausible projections were taken as exaggerate estimates. His fame rose and fell in a heartbeat, and he died the lone crusader of his scientific cause before someone picked it up again to find truth in it. From Rai, to Levin, to Weber’s widow (also a scientist) herself, the scientific community proves its unconditional faith in a wider-than-life mission. For all that’s left undone or yet to be found, someone else will complete it, explain it, solve it. As Rai puts it, “It won’t be in my lifetime, but that’s not important.”

The summit – September 2015 – now has a date. On the first advanced science run, both LIGO sites were locked to allow data collection. Scientists freed the places from human supervision leaving two delayed and disrupted instruments alone for two hours overnight – that’s when the machines recorded the sound. A signal so incredibly loud and clear to be able to frustrate teams of scientists before it could actually thrill them. Two black holes had circled each other, a long time ago and for a long time, until they collided, melting together into a bigger black hole. The sound of the impact has travelled to us in the form of gravitational waves from 1.4 billion light-years inserting itself in the exact, brief split of time that quickly followed the machines operability. Sharing the accomplishment of her community, Levin writes with palpable enthusiasm of how the news reached her through an e-mail – preciously signed Rai and Kip – of the hours she spent in silence, “trying to believe viscerally.”

To the end of the book, Levin delivers a taste of splendour. She anticipates future intents and promises new domains of exploration, she confesses limitedness but also states the goals in which she quickly indulges: her own detection of humanity at its fullest.

“We’ll continue to send a portrait of our best selves into space, a declaration that we were here, that we strove for understanding, that we often failed and occasionally succeed. We heard black holes collide. We’ll point to where the sound might have come from, to the best of our abilities, a swatch of space from an earlier epoch.”

About Susanna Princivalle

Susanna is a graduate student with a Bachelor's Degree in Modern Letters (Italy). She's written for The Artifice and The Orbital about films and literature.

https://euro-to-usd.com/