You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I’ll admit it. The last time I visited Achilles and the Trojan War wasn’t in Homer’s The Iliad; it was in Troy—that golden, glinting Hollywood creation full of brawn and blond and the thunderous knocks of shield against sword and armour, in which Brad Pitt plays the Greek hero with the compromised heel and Garrett Hedlund, who will soon appear in cinemas everywhere as Dean Moriarty in On the Road, plays his beloved cousin Patroclus, best known for donning Achilles’s armour and leading his Myrmidons into battle. King Agamemnon, who oversees the Greek expedition to Troy, had offended Achilles’s pride by appropriating Achilles’s war prize, the peasant girl Briseis, for himself; and Achilles, secure in the prophecy that Troy will not fall without him, famously retaliates by refusing to fight. We all know what happens next: Hector kills Patroclus. Achilles kills Hector. Achilles dies, as the gods foretold.

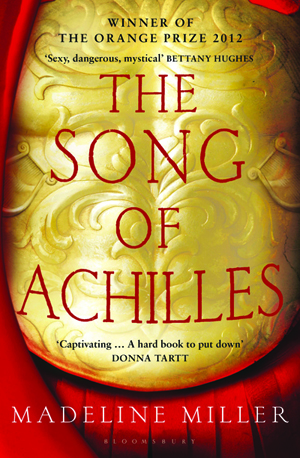

Madeline Miller’s 2012 Orange Prize-winning debut, The Song of Achilles, is a retelling of these events, with two twists: it is told from Patroclus’s perspective, and Patroclus is not Achilles’s cousin—they are lovers. In ancient Greece, the bond between Patroclus and Achilles was viewed through the social custom of paiderasteia (although in Miller’s novel Patroclus and Achilles are the same age, I suppose so that we may conceive of their relationship as one of equals), and Plato’s Symposium readily assumes that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers, its characters “arguing over who was on top”, wrote the critic Daniel Mendelsohn; so it would seem that the idea isn’t particularly new. What inspired Miller to write this book, however, is the intensity of Achilles’s mourning when Patroclus is killed, how he refuses to burn Patroclus’s body even days after his death. In the reader’s guide to her novel, Miller asks, “Why? Who is this man whose death could undo the mighty Achilles?” An interesting question, but Miller’s attempted answer is unsatisfying.

The Iliad has inspired many more films and books since Virgil’s The Aeneid. In retelling such a well-told tale, Miller faces some challenges: How to make an old story seem new? How to deal with the inevitability of its ending? How faithful does it have to stay to the original—or at least, its recognised variations? Luckily, Patroclus is a character still relatively free from the popular imagination, so Miller has some room to manoeuvre.

She does a good job of hinting at the two sides to Patroclus: the gentle healer, on the one hand; and the man who loves a half god of war and wears his armour into battle, his own capacity for violence unleashed by the headiness of being Achilles. Patroclus made a decision to take up medicine over arms, but he nevertheless savours the fear the mere sight of Achilles’s armour inspires in the Trojans and the awe it inspires in his fellow Greeks. We almost forget that blood is not new to Patroclus; he killed his first man—the son of a nobleman who had taunted and insulted him, a prince (at least, in appearances)—when he was only a boy. It was an accident, but Patroclus confessed, “I am making excuses. It was also a land of rocks.”

Patroclus’s anger was fuelled by feelings of insecurity and resentment, sowed by his critical father King Menoetius. Though he was born a prince, he has never lived the life of one. Like his “simple” mother, Patroclus was a constant disappointment to his father: “I was not fast. I was not strong. I could not sing. The best that could be said of me was that I was not sickly.” Even before he meets the golden-haired, swift-footed Achilles, he watches him from a distance and comes up hard against edge of his own impotence. His father’s cruel words come back to him, again and again: “That is what a son should be.” The dichotomy between who Patroclus is supposed to be and who he is makes him a sullen teenager, quick to be defensive—until he is “chosen” by Achilles, whose unquestioning regard softens him and bolsters his self-confidence.

What’s fresh about Miller’s retelling are the scenes that unfold before the war, when Patroclus and Achilles are only boys—how they come to be friends, then lovers: first, when Patroclus is exiled to Phthia, after he kills Clysonymus, to live under the care of King Peleus alongside his son Prince Achilles; and then in Mount Pelion, where the two boys learn fighting and healing skills from Chiron, Master Centaur and teacher of heroes. Miller spools out these formative years—in fact, it occupies half the novel—and yet, there is something of the glossing over about it, of depths yet to be plumbed. When King Peleus asks Achilles why he chooses Patroclus, of all the other foster boys who vie for Achilles’s attention, as his therapon (“a brother-in-arms sworn to a prince by blood oaths and love”), all Achilles says is, “He is surprising.” Not much of an insight.

In a retelling of a famous story, we already know, more or less, what happens. But where a writer might seek their own explanations for certain events or character traits, Miller seems to have taken them at face value; there is an underlying feeling of boxes being ticked off. Revealed in chronological order, The Song of Achilles moves effortlessly from scene to scene, but in doing so it sacrifices details that might invest the reader deeper in the story. Despite its epic scale, it perhaps suffers from being too thematically narrow, centered as it is on the love story between Patroclus and Achilles, relegating other characters, who might have lent the two lovers more interesting dimensions, to the sidelines. Even Achilles never completely comes to life, never really becomes human. Sure, he is half god, but he is also half mortal, his destiny pulled in two opposing directions: towards Patroclus, who serves as a grounding influence, and his mother Thetis, a goddess who disdains mortals and their “mediocrity”.

Perhaps part of the problem (though I hesitate to call it such) is Miller’s writing in first person from Patroclus’s point of view. It is, I think, limiting in some ways, although at the same time it does give Miller the opportunity to weave her magic when she comes to an unconventional dilemma towards the end of the book: her narrator dies. It is an odd place to be, but Patroclus, whose burdened soul is unable to move on, speaks from the dead utterly convincingly; he hovers, seeing everything, at times seeming to inhabit the eyes of Achilles.

Any writer retelling a famous Greek myth has to decide what role the gods should play. In this, I think Miller has struck a fine balance. A notable omission she made is of the enduring myth of Achilles’s heel. In fact, that oft-repeated story is not part of Homer’s The Iliad, in which Achilles was simply portrayed as extraordinarily gifted in battle, not invincible. That story only came about a thousand years later: to make Achilles immortal, Thetis brought him to the River Styx and dipped his body into its magic water; however, because she held him by the heel, his heel was unprotected.

Presumably, Miller chose to follow The Iliad’s explanation of Achilles’s invincibility because she was leaning towards a realist retelling, notwithstanding the fact that the sun god Apollo and the river god Scamander both interfere in the war—Apollo plucking Patroclus from Troy’s walls repeatedly as he tries to scale it, Scamander fighting Achilles when he chases after Hector. Still, there is something of the elemental about them, divine presence as nature; Thetis is the only godly being to inhabit any concrete form, more monster-in-law than sea nymph.

Miller’s novel is often a pleasure to read. The formal elegance of the voice she employs is just right, setting us in the right mood to immerse ourselves in these ancient times. She turns some beautiful phrases, so lyrical I find myself going back to them: “nut-brown bodies slicked with oil”, Achilles’s feet when he runs—“tendons that flickered like lyre-strings”, “heels flashing pink as licking tongues”. Such poetry is best when it comes precisely and sparingly, and though Miller is generally controlled with her prose, she does overwrite certain scenes that risk becoming purple passages. The love and sex scenes take on the voice of a breathy, pubescent teenager, which Patroclus is—a teenager, I mean—but he is also Patroclus, “best of the Myrmidons”, whose lover is Achilles, “best of the Greeks”. They are not just any teenagers.

In the end, what I most enjoyed about The Song of Achilles was the sense of possibility: that Patroclus and Achilles might outrun fate, even if at the back of our minds we know they will not. Divine prophecy dictates that if Achilles does not go to Troy, he will be forgotten; if he fights, he will live in history as an eternal legend—but he will die; however, his death will come only after Hector’s, second only to Achilles at his skill in battle. When Achilles hears that, he says, “Well, why would I kill him? He’s done nothing to me,” and it becomes a kind of grim, joking refrain. Somehow Miller manages to create suspense in her story, even though we already know how it will end.

There are some books you can read once, twice, many times, and every time you will find something new, a nuance you hadn’t picked up on before. I don’t think The Song of Achilles is that sort of book, but I enjoyed it nonetheless. What it does is whet one’s appetite for more of the same, and I daresay that the next book on Greek myths I pick up will be the father of them all, The Iliad, which I’m sure the Classics teacher in Miller would be very happy about.

First published 5 September 2011. Available in hardback, paperback, ebook and audiobook from Bloomsbury and Amazon. Thanks to Bloomsbury for providing a review copy.

About Emily Ding

Emily joined Litro in April 2012 as Literary Editor & Web Designer. She made over the website and introduced new developmental and editorial features to strengthen Litro's online presence. She left her position in January 2013, taking a backseat as Contributing Editor to concentrate on writing. She is a freelance journalist with a special interest in travel writing and foreign reporting (with an inclination for Asia and Latin America), and is now based in Malaysia. English is her native language, but she also speaks Mandarin and Spanish, having spent 2007-08 travelling in Central America.