You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

There’s an interesting narrative technique – F. Scott Fitzgerald uses it, and so does Herman Melville – that entrusts the telling of a story to a witness, a peripheral character. How different a tale would The Great Gatsby have been if heard from the mouth of Jay Gatsby! How dizzying the reading experience if Melville’s readers had been made privy to Ahab’s thoughts! It’s a brave technique: the filters of Nick Carraway and Ishmael risk a dilution of impact; the reader is placed at a remove from the plot’s driving force. This removal is particularly uncomfortable for modern readers, who have glutted on Woolf and Joyce (and so many others) and now feel entitled to their protagonist’s every emotion.

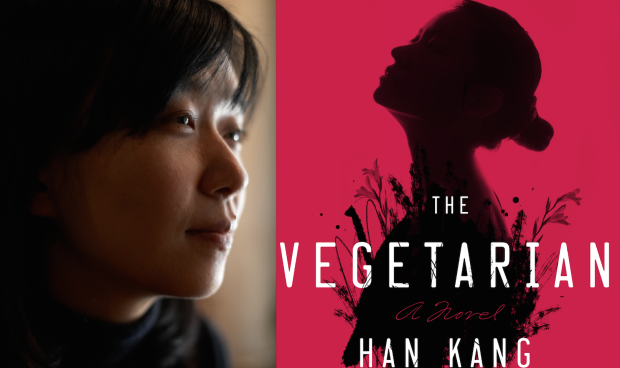

And yet, this distancing is precisely what is so compelling about Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, published last year by Portobello Books. “Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way.” This stunningly unemotional sentence opens the book, introducing us to Yeong-hye, the eponymous vegetarian at the centre of the story, and her husband, who voices the book’s first section (the second is focalized through the experience of her brother-in-law, and the third her sister’s experience; both are written in close third person). Our only insight into the mind of Yeong-hye is through rare italicized passages. As she subsumes herself in vegetarianism, and then – as the narrative gets stranger and stranger – stops eating altogether, willing, dreaming, believing herself to be a tree, these passages drip-feed to the reader a series of disturbing, grammatically unsound thoughts. “Animal eyes gleaming wild, presence of blood, unearthed skull, again those eyes,” we read. “Hand, foot, tongue, gaze, all weapons from which nothing is safe.”

Put straightforwardly, the book describes the consequences of Yeong-hye’s decision to become a vegetarian: from the social embarrassment of her husband, to her brutal self-harm after being force-fed a piece of pork by her father. We observe her unnamed brother-in-law’s growing sexual obsession with Yeong-hye, and the disintegration of her sister’s marriage as she pays visits to the psychiatric ward where Yeong-hye refuses food. But this is an over-simplification: nothing more than the hooks upon which the story is hung. The tapestry of the novel is so much richer than these moments of narrative drama.

E.M. Forster recognises the inadequacy of plot-points as means of describing (or constructing) a novel. Against “plot” Forster pits “human individuals”. “Plot” – which he imagines as “a sort of higher government official” – is confronted with human characters who are “enormous, shadowy and intractable, and three-quarters hidden like an iceberg”. “In vain,” he goes on to write, does the plot point out “to these unwieldy creatures the advantage of the triple process of complication, crisis and solution so persuasively expounded by Aristotle”. Plot itself is given a voice, a churlish voice, determined to alleviate its own importance: “Characters must not brood too long,” it demands. “They must not waste time running up and down ladders in their own insides, they must contribute, or higher interests will be jeopardized.”

I can’t imagine Forster sitting down with the slim volume of The Vegetarian: it seems too bizarre a book for the man Zadie Smith calls “an Edwardian among modernists”. But were he to have read it, he might have found within it an adherence to the tussle between plot and character expounded in Aspects of the Novel. The plot of The Vegetarian is indefinable: it is tethered to the strange whims and thwarted desires of its central characters. There is no Aristotelian solution here.

The language, too, is something Forster might have admired. Translated from Korean by Deborah Smith, it is simple and enthralling. It is largely free from imagery – aside, that is, from the violent interruptions of Yeong-hye’s dream-world, bloody and surreal. The disintegration of Yeong-hye’s sense of self is charted with disturbing clarity: Yeong-Hye, we read, had

removed her hospital gown and placed it on her knees, leaving her gaunt collarbones, emaciated breasts and brown nipples completely exposed. The bandage had been unwound from her left wrist, and the blood that was leaking out seemed to be slowly licking at the sutured area. Sunbeams bathed her face and naked body.

Later, we learn that “[o]nly Yeong-hye, docile and naive, had been unable to deflect their father’s temper or put up any form of resistance. Instead, she had merely absorbed all her suffering inside her, deep into the marrow of her bones.” Han does not flinch from physicality.

As a reader hoping to convey to other, prospective readers the measure of this book, I now reach a sticking point. I can’t convey it through the windings of its plot, which is too unruly to allow for a neat summing-up. And – to draw on Forster’s binary – I can’t rely on the “human individuals”; the impressions of the peripheral characters are too slippery, too self-serving, and the voice of Yeong-Hye, the vegetarian at the centre of The Vegetarian, is rarely heard, and barely intelligible when it is.

The best I can do, then, is reiterate the questions this novel asks. What does it feel like to make an enemy of your own body? This is the novel’s biggest question. How do people respond when social norms are disregarded? What does it mean to have an all-consuming desire? And how can you live when that desire is frustrated – or fulfilled?

Han tackles these questions with a story which is, paradoxically, both enlightening and incomprehensible. It is a strange book, with overtones of Kafka, and a plot that has no resolution. And yet it consumes its reader, turning the seeming banality of a woman’s decision not to eat meat into a surreal psychological odyssey.

The Vegetarian is published by Portobello Books.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.