You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

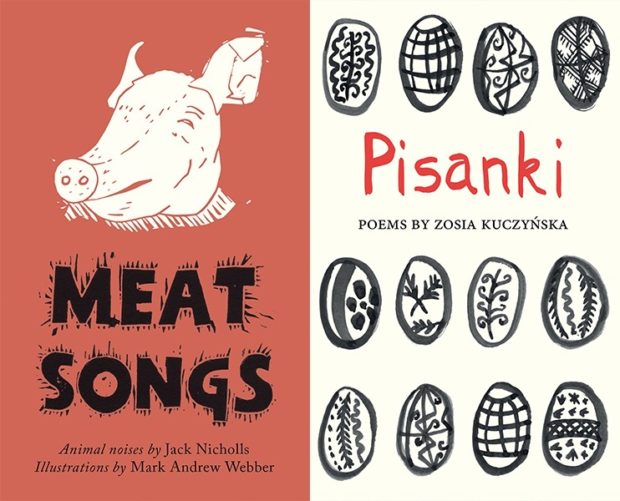

Go shoppingMeat Songs by Jack Nicholls, with illustrations by Mark Andrew Webber, is a fourteen-piece pamphlet that approaches the human-animal relationship from a stark array of angles. These poems and prose poems are not simply love letters to loyal companions; instead the reader is presented with Blakeian explorations into perspectives: the points of view of animals, their owners, eaters and interlocutors. We are invited to consider and reconsider the built environments we share and prepare for animals – the cat cafes, farms and fish bowls – from the occupant’s point of view and how animals might understand these constructed places.

Space and the often unconsidered way we share it with living things is a theme which runs throughout this debut from Nicholls, as he swings the lens around to face us, letting animal scrutiny of our bodies become the focus. The first piece in this pamphlet, “Headlouse”, re-evaluates human–nit interactions, the intimacy of the act of feeding off, and whether symbiosis is ever really possible. “I have eaten so much of you”, the narrator louse declares, but “I do not know if you are enough”. The inevitable, chemical tang of medicated shampoo is recalled, as is the murderous intent of the sharp, silver teeth of a nit comb: “everything was agony and you yourself was agony”. But the louse reasons, “It was you trying to care for I, or some of I”. “You are family”, the louse suggests, “I am as full of your blood as you are”. It’s a striking comparison to make, drawing attention to the lack of choice we have for what we are born in to, alongside the see-sawing selfish/selfless arguments surrounding the acts of caring for animals.

Meat Songs is also deeply concerned with food and animals as the source of food, it being impossible to consider our relationship with pigs, sheep and cows without acknowledging the hierarchical chain that permits their industrial farming and consumption. Nicholls chooses to let the politics of this run as an undercurrent as we read about the experience of sitting on supermarket shelves in “Ground Mince Sonnet”, the slaughterhouse in “Severed Pig’s Head”, or, in “Baa”, one logical conclusion to intensive farming processes: that all animals, including people, be replaced by sheep. If there were any questions over the appropriateness of this, the poem has an answer: “Oh, sheep are better, that’s why. Quiet and blank and their eyes are lightless. And when they speak, they sound like they’re grieving”.

Voicing these experiences lends a disconcerting edge to the poems, from the objectivity of the legal ramifications of romantic relationships with animals in “Caroline”, to the first-hand, horizontally-formatted piece “White Tiger Farm”. Dogs, in particular, are given their own language, which is an excitable stream describing violent control in “Who’s a Good Boy?” and a gargling, water-clogged tongue in “Hounds of Love”: “Me Im th turbl creature / o th lake, llong drown now / n rot n et, rrr”. This lends the pamphlet a surrealism which is both tempered and honed by the thick-lined, black and white prints of cartoonish animal illustrations by Webber. But it’s precisely this weird, other-worldliness which makes Meat Songs such an intriguing pamphlet, and reading these pieces becomes very serious, sometimes even disturbing, fun.

*

Zosia Kuczyńska’s Pisanki offers another distinctive approach through an under-heard voice, in this instance the experience of Polish children removed to India during the Second World War – and Kuczyńska’s grandmother in particular. According to the introduction by Bernard O’Donoghue, Maria Juralewicz was one of two thousand children taken unaccompanied to Maharashtra from Siberia in 1942. Kuczyńska’s pamphlet traces the experience of this particular journey, alongside pieces which explore acts of journeying, immigration and integration.

The markers of the journey made by Maria Juralewicz, across land and sea, eventually to the UK where she settled, are often startling. A field of discarded guns in “The train from Arkhangelsk to Bukhara” is so odd it could be a performance art piece entitled “Midas died of hunger”. After becoming separated, Maria’s brother reappears in Tehran at Eastertime, where a boiled egg reveals “the improbable marigold / of a new life” in “Brother Staś”. In “Rochdale Nativity”, her daughter – “whose heart and soul are homophones reserved / for the mastery of second languages” – becomes a marker of this movement’s end, as the next generation’s experience of this new place will be easier.. Movement in itself is unsettling; in “Vection” (the word describes the feeling of moving whilst remaining stationary), a person called Aniela experiences the memory of passage and “flinches like a railway passenger / delivered from a dream of their own movement”, unsure if she has changed or if everything else has changed around her.

Alongside these markers are the mark-making practices of those journeying that become ways of resituating a person or place, to re/establish home: Polish acts such as pisanki (decorated Easter Eggs) and paper cutting (wycinaki), or in “Pyriform”, the paperclips hung in place of pears on a tree too young to bear fruit, planted by Maria for a grandchild. “Sarah Jane’s Geranium” captures both the literal and metaphorical difference of a potted-plant as opposed to a flowerbed, as well as the symbolism of these different root structures, and how one allows for travel and the other for growth: “Some nights you think that home is relative / to time spent watering the same flower twice / a day”.

Finally, there is consideration for the act of biographic storytelling woven in to the history of silk. “On Hosiery”, the last of the twenty poems in this pamphlet, the romance of an origin story involving a Chinese empress connects to the sought-after stockings in the Second World War which were replaced by tea-stained legs and the shaky kohl lines of drawn-on seams. “Survive to hope”, Kuczyńska writes, which suggests both a mantra performed by the refugees she voices as they travel, and a way to understand the act of storytelling and its consequences: “that every damage done as though by moths / can be told as art or history or both”.

The central thread of this pamphlet is a family tie which creates connections across time and place, between the homes we make and re-make, as well as the individual experiences of the mass movement of people, all voiced in vibrant language in another compelling debut from The Emma Press.

Meat Songs and Pisanki are published by The Emma Press.

About Laura Tansley

Laura Tansley's writing has appeared in Butcher's Dog, Cosmonaut's Avenue, Lighthouse, New Writing Scotland, PANK, The Rialto and is forthcoming in Stand, Tears in the Fence and Southword. She is also co-editor of the collection 'Writing Creative Non-Fiction: Determining the Form'. She lives and works in Glasgow.