You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Every so often, a country will receive the honorary accolade of “the sixth Nordic country”. Is it Scotland, with its Viking links and social-democratic aspirations? Is it the Netherlands, with its unusual fondness for salmiakki? Or is it Estonia, just a short boat ride from Helsinki? There is one country, however, that is rarely in the equation: Poland. This is perhaps surprising, given that it once shared a monarch with Sweden. And there is a particularly unusual string to Poland’s Nordic bow: its love of sagas, Norwegian romance fiction known for its steamy love scenes. While brands like Harlequin and Mills and Boon have global recognition, the Norwegian romance stories are rarely translated into languages other than Swedish, Danish, Icelandic… and Polish, the language of its biggest market outside Scandinavia. What is it about these stories that so appeals to a Polish readership?

The romance section in the main building of Gdansk library in Poland is brimful of paperback books by Norwegian authors. There are thirty to sixty books in a series, each about 200 pages long. I pick out few copies to see their covers. They essentially follow three patterns: a young woman with long hair either holding a baby or by herself but with nostalgically blurred men faces floating in the background, or a couple in a passionate embrace. The collection consists of the bestselling titles: The Legend of the Ice People by Margit Sandemo, Raija by Bente Pedersen, Daughters of Life by May Grethe Lerum. I decide to go with The Three Sisters Saga by Bente Pedersen – volume 15. Full of hope that the story will deliver on its promise made on the cover – “A saga that will tug at your heartstrings” – I head to the check out desk.

Poland swiftly fell in love with Norwegian sagas. The first series to appear on the Polish publishing market, The Legend of the Ice People, debuted in 1992, ten years after its original Norwegian release, and has been reissued ever since; the first English-language edition was not launched until 2008. Since that time, Norwegian romantic sagas have been steadily growing in popularity in Poland: Sandemo is reputed to have sold around ten million copies there.

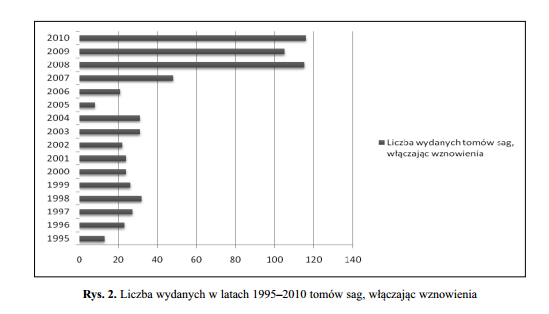

“Since 1992 we could observe a steady number of publications throughout the ’90s and ’00s, with a rapid increase in 2007 when the number of published volumes doubled. In the following years it even tripled,” explains Katarzyna Tunkiel, who works as a translator and holds a PhD in Norwegian literature from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan. She estimates the number of volumes published every year in Poland at 120, including both new titles and reissues of Sandemo’s classics. “In comparison, around 200 volumes are published yearly in Norway,” she adds. Małgorzata Rost, a Norwegian-Polish translator who translated the saga that I would soon choose to read, confirms that demand is definitely there: “I’ve been working with sagas for the past eight years for three different publishers.”

I have never read Norwegian sagas before, but I have been aware of their existence since I was a teenager. In the opening chapter of the book that I have borrowed from the library, I am introduced to the life of beautiful Aile with an uncanny gift of helping people in life-threatening situations. She and her family are Sami – Norway’s indigenous people who live on reindeer herding. Aile is an independent and rebellious soul who resists explaining herself to anybody – the reason why she still isn’t married. In this world of traditional values, setting up a family is an ultimate goal. Aile wants to marry for love, but her heart belongs to a man she can’t marry.

“A strong female protagonist is a must,” continues Tunkiel, “accompanied by a whole gallery of other characters, whose lives, with all their ups and downs, are described using a simple language full of literary cliches, especially when it comes to the romantic or erotic bits.”

Sagas are traditionally set between the 17th and 20th century in the remote Norwegian countryside or in a small town. The term “saga” was coined by the Polish publishers: Norwegians call them serial novels, since the original medieval sagas are narratives about the Viking age in the Nordic countries and are most associated with Iceland. But Katarzyna Tunkiel understands why it makes sense to use the term nowadays. “Some of those medieval sagas are focused on family history and often contain such elements as love, hatred, conflict, revenge and murder. In this respect, the contemporary genre of romantic novels may be seen as a sort of continuation of this old literary tradition.”

Zofia Filipkowska, a pharmacist, first read The Legend of the Ice People when she was 13. The series provided an enjoyable mix of fantasy elements and romance. However, she didn’t finish the whole series: she was only buying volumes that were available in secondhand bookstores. Eventually, the series was published in chronological order in the pages of women’s magazines or tabloid newspapers. When she got pregnant with her first child at the age of 28 and had some time to spare, she downloaded all volumes from the internet. “I know it is not a highbrow literature, but it works similar to TV shows – the more involved you are, the better you know the characters. Besides, my home is my castle and I can read whatever I want.”

Rost believes that it all depends on what you are looking for in a book. “People often think of these books as something embarrassing or a guilty pleasure, but at the end of the day it’s just entertainment and you can’t be all about Dostoyevsky and Proust all the time. Sometimes you just want something engaging – there is nothing wrong with that.”

Sagas might not aspire to explore the nature of humankind but there is great emphasis on characters’ efforts to be a good person. Aile from The Three Sisters Saga is devoted to her family. Her eagerness to take up tasks which are traditionally carried out by men like killing a reindeer is a signal of a girl power spirit. She has been faced with a lot of painful experiences, including the death of her father for which she blames herself. A male character has also come into the picture to console her. Gripping action and brevity are of essence and soon I arrive at the first erotic scene, where Aile, to the discontent of the current admirer, looses herself in an act of love with a man from the past.

“The sex scenes can be either very literal or full of cheesy metaphors,” says Rost. In one of the books she translated the erotic bits were so tasteless she asked the editor to remove her name. “I was terrified that someone I know (and by that I mean my proud grandparents who were always on the lookout for my translations at the newsagents) would get their hands on it.” There are authors, however, who handle the subject without going into too much detail, but she and her translator friends remember the dreadful lines best: “We always exchange stories about the weirdest plot elements, including the most horrifying sex scenes. If I remember correctly, the most cringe worthy line I have ever translated was: ‘Drops of sweat forming like a pearl necklace on the hair around the throbbing member.’ Oof.”

Why are these books so popular in Poland of all places? One factor may be Poland’s academic infrastructure: both the University of Gdansk and the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan boast excellent Scandinavian Studies departments. But that can’t explain everything. After all, counters Tunkiel, “there are even more translators of Norwegian literature into German, and Germans are known to love everything Scandinavian, but the romantic series from Norway don’t exist on the German publishing market”. She recalls a Norwegian journalist concluding that the phenomenon of sagas’ popularity originates from the fact that most Norwegians are farmers and fishermen at heart (dominant occupations in the books). “I guess the same rule applies to the Polish readers, even though we tend not to be as open about it as Norwegians.”

In one of the interviews for the Polish audience, Sandemo tried to grasp the phenomenon herself. She interpreted the mystical bond she has with the Polish readers as the extension of the mystic elements present in her books. The answer to the question of why sagas are a hit in Poland seems to be as elusive as Sandemo’s explanation. Maybe it’s the allure of the Scandinavian countryside or the absorbing storyline written with bite-size sentences. It’s also convenient to grab a book one buys together with a morning newspaper. Katarzyna Tunkiel says they are a literary answer to dramatic TV series with an extra spicy twist in form of some eroticism. “They had been there long before E.L. James made a breakthrough with her Fifty Shades trilogy!”

When it comes to Aile, she hasn’t arrived at her happy ending just yet. The last chapter reveals that there are few more obstacles to overcome before she can settle down with a man of her dreams. To get closer to finding out who that will be, I need to borrow volume 16.