You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The bus spits them out in the shadow of the museum. The heat wave has advanced on the city, wilting everything in sight: the dusty caged shrubs, the panting dog, the damp leaflets on the pavement. Looming on top of Meg and Roxy are the great stone steps, with Meg’s mother, beckoning. Dove looks like a little old lady, but Meg knows better than this. For Meg, her mother’s the priest, and this could be the entrance to a Mayan temple where her heart’s about to be ripped from her chest.

Her mother steps gingerly towards them. Bunions distort her espadrilles. She’s light, so light, her scaffolding could snap like wishbones. Come a strong wind, Dove’ll be borne up, blown away with the same look of surprise and reproach, the same space around her poached egg eyes, her tight coils of red hair rising with the air current, a Momma balloon, up and away and Meg down here, holding onto the string until she can’t anymore.

“Hurry,” Dove cries. “Poppa’s getting the tickets.”

Roxy, Meg’s seven-year-old, looks down at the pavement and tightens her death grip on Meg’s sleeve, “I don’t want to go.”

Tiny for her age, she has fluffy mink-coloured hair. Her brow knits as Meg’s voice comes out in a harsh little yelp. “You have to,” her mother says. And then they ascend. To the Temple of Doom.

Inside it’s refrigerator cool, the canned air re-circulating and smelling, oddly, of fur. They call it The Great Hall for a reason. Meg’s father, Jacques, is dwarfed. He used to be like a dark star, magnetically dense. Once Meg coldly took videos of how he stood too close to people as they backed away, then wrote a paper called “The Exigencies of Personal Space.” Maybe it was childhood, but he loomed large, blocking every path. Now his pink face screws up with worry, “You’re late. What took you so long? Come on.”

After fidgeting in the line, they make it to the planetarium. The seats are covered in red chenille, the luminescent sky, a concave dome. Morgan Freeman’s velvety voice emanates from the ceiling, “Billions and billions of stars with their own planets. Trillions of universes.”

“It’s God,” Roxy whispers. “He’s talking to us.”

“God was the woman’s voice at the beginning,” Meg says. “The one who told us we couldn’t take photographs.”

“No,” Roxy says. “God has a beard. He’s old.”

“As long as man has been on earth,” Morgan says. “He’s looked up in the sky and wondered.”

Dove and Jacques sit across the theatre, pinned in their seats behind the slack rope. They seem lonely, trapped, and yet they yearn, or so Meg thinks. She feels guilty. She’s not a very good daughter. She doesn’t enjoy this enough.

Morgan’s voice floats down from the Milky Way. “How is it possible that we’re so completely alone?”

They sit through the Big Bang, the spinning chunks of black rock, the orgasmitron of light and sound, then stumble out.

“Did you like that, Roxy?” Jacques says.

“It’s too bad he dies,” Roxy says.

“Who dies?” Dove cries.” What’s she talking about?”

“God,” Roxy says.

“It wasn’t god,” Dove says. “It was a recording. There is no god. That’s why he didn’t die.”

“I’m dying here.” Jacques bumps Meg from behind. “Come on. Move.”

“Bye God,” Roxy whispers. “Goodnight.”

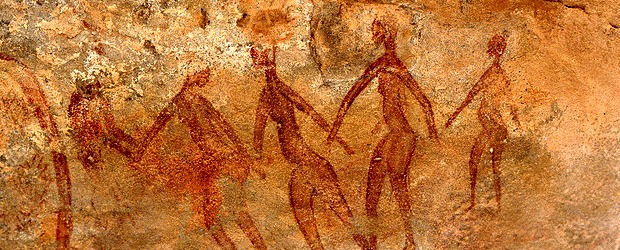

They travel from the Milky Way to the prehistoric Hall of Man. On school trips a long time ago, Meg lagged behind looking at the shadow boxes of the Savannah, the Steppes, the Rainforest, the Plains, the Arctic, complete with real animals, shot and reassembled with dead fur, seams of glue, dusty marbles replacing eyes.

Dove stops in front of a trio of small Neanderthal women crouching at a cellophane campfire while Neanderthal men walk away with big spears. “See, Roxy,” she says. “The women are cooking, and the men are running around pretending they’re hunting like a bunch of damned fools.” She turns around and takes a nip from a mini-bar bottle of Tanqueray in her purse.

At lunch Dove treats herself to a full glass of Chardonnay. The rest of them meekly prod their grey plastic trays along the little cafeteria rails past the waxed Red Delicious apples, the boxes of milk on chipped ice, the piece of glaucous pizza fungating under a heat lamp. Roxy plucks out a biodegradable plate of Caesar Salad. Jacques makes a pyramid of corncobs over a matte slab of brisket. When they sit down on the moulded orange seats, Roxy leans sadly over her slice of cheesecake.

“Honey, it’s too late,” Meg says. “I paid for it.”

“But I wanted the chocolate,” Roxy says.

“Oh, be quiet,” Dove says. “You blame everything on everybody.” She gives Roxy’s arm a good pinch, and Roxy blinks hard. Meg inhales sharply, but Dove takes an unconcerned sip from her pee-coloured wine. “You’re just like your grandfather,” she continues to Roxy. “Jacques went to his print studio and the woman there said his print needed more purple, and so he put more purple, and then he came back and said, ‘That woman ruined my print.’”

Jacques pats Roxy’s knee. “Look at you. You’re growing up, kid. That’s for sure.”

“Oh yes, she’s growing up,” Dove says. “And look, Poppa’s growing up. He’s growing up; he’s out of diapers. Roxy, can you see Poppa in diapers?”

Jacques eats big spoonfuls of Roxy’s cake. The Danish family on their left stares, juice boxes stopped, mid-trajectory, the father holding a chicken wing. In the big white stone hall, Roxy pulls Meg aside. “Tell her I didn’t like it when she said that.”

“Just let it go, she’s old,” Meg says. “You can’t tell old people things.” But she does corner Dove by the Cro-Magnon skulls.

“What’s the matter with her now?” Dove says.

Meg hears herself explaining that she validates Roxy’s feelings. She pictures Dove covering her ears and saying “la la la la la.” They’ve drifted to the weapons cabinet, Dove conveniently framed by a Cro-Magnon with a slingshot. Meg tries hard not to focus on this. “She’s only been on this planet seven years, ma. Try to be flexible.”

But Dove’s eyes mist over so she can barely see. Roxy hardly knows her. She has never tried for even a moment to listen to anything Dove has to say. Roxy didn’t thank her for the book she got her last year for her birthday, Anne of Green Gables, a story Dove loved so much as a child she kept it under her pillow for a year. Or the Christmas present of some impenetrable electronic thing. And look at Meg. Really look at her. Meg is getting old. There are little lines on the side of her nose. The corners of her mouth turn down like Jacques’. Her hair is red, dyed, to resemble Dove’s own natural colour, though sun-fried in places. She’s gone thick around the waist. To think Meg’s middle name is Rose because roses are the most lovely flower, beautiful in every stage: a bud, barely open, and in full bloom. But this is so not true. There is no beauty in decrepitude. And yet Dove remembers holding Meg’s hand when they went to Macy’s together. And the time she bought her white toe shoes when all the other girls had pink. How she scrimped and saved to make her happy. And look how Meg repays her, how harshly she judges. “Give your mother a break,” Dove cries. “For once in your life.”

But Meg has managed a neat trick she’s never done before. She’s some place far away, the Milky Way, a mother-daughter-nugget, spinning helplessly through space. Though, in a way, so free. This is what she never knew and feared. Relax. Don’t hold on so tight. She feels such joy. Oh, Meg thinks, she must teach Roxy this.

About Lisa Alexander

Lisa Alexander is the recipient of the Fugue 2013 Prose Award, and the UCLA James Kirkwood Award for Fiction. Her work has also appeared in Southern California Review, Fugue, Meridian, Cimarron Review, The Common, and the anthology, Mourning Sickness. She received her MFA from Bennington College, and is currently working on a collection of linked L.A. stories.