You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

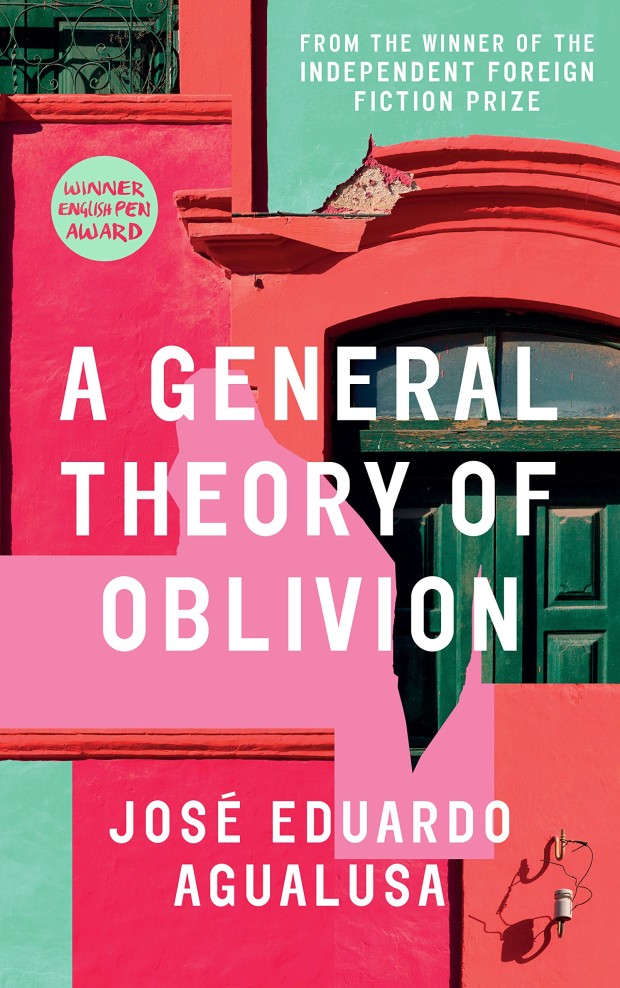

A General Theory of Oblivion by José Eduardo Agualusa tells the story of Ludovica Fernandes Mano (Ludo for short), who – on the eve of Angolan independence – withdraws into her apartment, determined not to observe the changes occurring beyond her walls. This is no metaphorical isolation: “She unlocked the front door,” we learn, and “began to construct a wall in the hallway, cutting off the apartment from the rest of the building. She spent the whole morning doing it. It was not until the wall was ready, and she had smoothed down the cement, that she felt hungry and thirsty”. She doesn’t emerge again for thirty years. Agualusa’s readers are presented with patchwork impressions of the arrival of independence: news from the radio, the observations Ludo commits to her diary (which, when out of paper, she begins to inscribe on her walls), and chapters devoted to the interconnecting lives of the characters beyond her apartment. Angola’s social history is rendered obliquely as a result.

This re-imagining of real events is reminiscent of Wolfgang Becker’s wonderful Good Bye Lenin!, which describes the fall of the Berlin Wall through the eyes of a man determined to maintain the illusion of the GDR for the benefit of his mother (who would, a doctor assures, die of a heart attack at the news of Germany’s reunification). And, of course, what piece could consider this kind of withdrawal from the world without referencing the famously self-isolated Miss Havisham, who, we learn upon meeting her, “has never seen the sun since [Pip was] born”? It is with horror at this halting of the natural progression of time that Pip observes that “every thing in the room had stopped, like the watch and the clock, a long time ago”. Like Miss Havisham, Ludo seeks comfort in visits from a young boy – Sabalu – although Ludo’s motives are kinder than Miss Havisham’s: she is genuinely affected by her interactions with Sabalu, who gives her her first hug “in a long time. She was a bit out of practice, and Sabalu had to lift her arms up. It was really him making a nest for himself in the old lady’s lap”.

When Ludo is working in the garden, she makes herself invisible to others by “using a long cardboard box, in which she had cut two holes at eye level for looking through”; anyone looking across at her “would see a large box moving around, leaning out and drawing itself back in again”. Soon, however, this state of unseeing comes to envelop Ludo herself: “Her eyesight had been getting worse and worse. No sooner had the light begun to fade, after a certain time of the day, than she began to move about just by instinct.” There is something of Marquez in the physical realisation of Ludo’s refusal to witness the history unfolding around her.

Then there is her diary-keeping, which seems to contradict her determination not to recognise the changes occurring in Angola. Her diary, written across the walls of her home, becomes a kind of anti-testimony, “a general theory of oblivion” in her own words. “If I still had the space, the charcoal, and available walls,” we read, “I could compose a great work about forgetting.” This “work about forgetting” begins to overtake her existence. “I save on food, on water, on fire and on adjectives,” she writes. It keeps her alive: “I cut adverbs/ pronouns/ I spare my/ wrists.”

A General Theory of Oblivion has much in common with Sleepwalking Land, a novel published in English in 2006 by another great Lusophone writer, Mia Couto. Set in war-torn Mozambique, Sleepwalking Land is inhabited by a host of characters, one of whom is a sightless prostitute. She is grateful for her blindness: “Thank God I’m blind,” she says. “Out there, the world is even worse. Because of this war, no one pities anyone else.” For this woman, like Ludo, time is confused by her blindness: “The blind woman mingled times,” Couto writes, “turning the past into the present”.

Couto’s prose has a similar feel to that of Agualusa – episodic, poetic, raw – and Sleepwalking Land shares with A General Theory of Oblivion the inclusion of a text within a text, this time the notebooks of a man named Kindzu. Both writers address African history through fragmented narratives which defy a single objective truth, echoing John Berger’s insistence that “[n]ever again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one”. The truth in both books is a filtered truth, one conveyed through subjective experience, and this is doubly so for those reading Couto and Agualusa in English; the words reach us through a second filter, that of the translator. In Gods and Soldiers: The Penguin Anthology of Contemporary African Writing, Couto troubles over this problem of translation:

Words do not always serve as a bridge between these diverse worlds… [C]oncepts that seem to us to be universal, such as Nature, Culture, and Society, are sometimes difficult to reconcile. There are often no words in local languages to express these ideas. Sometimes, the opposite is true: European languages do not possess expressions that may translate the values and concepts contained in Mozambican cultures.

And yet, never in Daniel Hahn’s translation of A General Theory of Oblivion into English do we feel that the prose lacks the precision of the original Portuguese. The translation is loyal to tonal changes within the novel, is sensitive to the movement from straightforward exposition to the strange lyricism of Ludo’s diary. Indeed, the prose is one of A General Theory of Oblivion’s most arresting qualities, and it surprises me, therefore, that it was originally conceived of as a screenplay. The story is full of striking images, but the state of unseeing at the centre of the novel – Ludo’s self-insisted blindness – would jar with the visual medium of film. Rather, it is in the details of the language that this narrative impresses: a story communicated, in Ludo’s own words, by “feeling [our] way through the letters”.

*

It should be noted that the Man Booker International Prize underwent an interesting change last year: formerly, the prize had been awarded every two years in recognition of a writer’s entire oeuvre, but – merging with the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize – it now seeks to recognise the author and translator of a single work of fiction with an annual award. To my mind, this undermines Pamuk’s and Agualusa’s chances of winning; A Strangeness in My Mind and A General Theory of Oblivion don’t feel as though they are the best representatives of their authors’ abilities. Similarly, while I enjoyed A Whole Life and The Vegetarian, I fear that they won’t be deemed to have the narrative scope required to clinch the deal. I hope I am wrong, however, as both books are beautifully translated and worthy of celebration. Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child seems the likely winner, although – in a slight side-stepping of the prize’s new format – it relies on the strength of the three previous books in the Neapolitan series for its impact. The biggest threat to Ferrante’s win comes from Yan Lianke, whose experiments with form make The Four Books a remarkable read.

A General Theory of Oblivion is published by Harvill Secker.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.