You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

For Jodorowsky and Ron Bushy

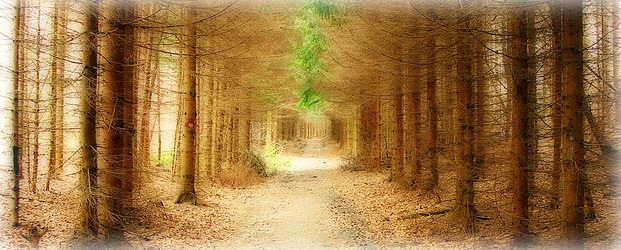

The pathway has a velour tenderness—though I’ve seen better. Anyway, you say you’re happy, and that’s what I care about. Or do I? At the end of the path lies—well, I’m not sure what lies at the end of the path. In any case, it’s more pleasant to linger. The trees have such big friendly leaves; they look like circus tents. The leaves and the darkness mingle, the night air is humid, and some kind of fancy insects are flying above the treetops. This park, or forest, or whatever you want to call it, might be beautiful. You keep wanting to stop and kiss. The people who stroll by in their jumpers and sneakers ignore us. I say: “What about your mom?” And you say: “We have pop music for forgetfulness.” “You’re quite the jokester,” I say. “I thought pop music was for vestigial religion.” “Hallelujah,” you say. [private] Then comes a guy down the path with his pug. Or is it a bulldog? In the dim light, I can’t tell, and as my old philosophy professor, Mr. Boner, used to say if you have to develop a procedure to tell, you won’t be able to. The old fellow with the dog says: “What are you kids doing out on a night like this?” And you surprise me by answering: “Do you remember when you were young and the nights were gloomy and mysterious, nature wet and breathing, and maybe it has to do with sex but nobody cares because everyone is dizzy with the spin of the world?” And the old man––the uniform he’s wearing isn’t FedEx like I thought at first – doesn’t answer, seems lost in his own dreams, and I pull you a few steps ahead thinking: why talk about sex with that guy, but you want to kiss again, and I never ask, and I feel myself slipping into your mouth, and man, I’m gone, and then we stop, and I’m back, and you’re breathing a bit madly, and I say: “Let’s go sit by that bank of primroses or are they daisies,” and you say: “The city has done a nice job,” and I say: “You’re kidding.”

After a while, we stand and walk.

I wish I could tell you how I got here. The world is so beautiful. I’ll admit that, but it’s also so present, constant, and unchangeable, and I say to myself: “I hope”—and then I don’t know what to say. And you sense my mood, saying: “You always get this way.” “I know,” I say. We walk a little further. Something disappears into the dense growth lining the path ahead of us, and I think, a roebuck? Or was it a person acting like a roebuck? I can’t tell. And what procedure do I have for telling? The old prof made quite an impression. “Maybe we should go,” you say. “Mom will be worried.” “I don’t blame you,” I say. “When I get this way, I’m a bear.”

***

A few days later I drive to Syracuse and have a lot of time to think about our love affair, and what we are really buying into, and how it relates to what lies outside our feelings. I was born in Ames, Iowa, and I took a degree in literature from Urbana, where I became vice/presi/dent of the Deconstruction Club my sophomore year. In graduate school, I began to study ‘pornography,’ developing the at-least theoretical possibility that rather than a reflection of an existent monetary culture, ‘pornography’ is precisely an ‘industry’ in the 19th Century sense that actually secretes its own mores et artes, which led me to devise optimizations of the general culture using marginal averages from the industry—pornographie, c’est nous. I was then arrested. The world I realized cannot be observed without involvement. The papers called me a pimp and a thug. I left ‘grad school’ in disgrace. The detective who handled my case showed me how theorization is the illimitable erasure and re-engraving of standpoint and by its nature fails to account for exploitation, even when its subject is exploitation. He then spoke to my probation officer. That’s how I got my job in the auto industry. I in fact have a remarkable talent for mapping the reflective points of funhouses. I developed a list of dealerships upstate. Hence my trip to Syracuse, which is the loveliest of cities.

***

First stop: Yates Buick. Yates is the guy who got famous when he traded a jalopy to a kid for a bit of poetry scribbled on a sheet of paper. It is not upon you alone that the dark patches fall. “Nice line,” he said, “and that kid will buy Buick for his whole career.” We meet in the parts department. “The packages I’m selling,” I tell him, “will goose your numbers.” We do our business. Ford dealer across town has a motto over his sales bay: Now as soon as soon as now. He thinks Yates is crazy. “Giving cars away for poems, fragments, you ruin poetry. You might ruin cars.” I tell him, “You don’t need poetry with my formats.” We conclude our business.

Later I grab a bite at Chili’s. The server is good-looking. I dial you on the cell. You don’t answer. There’s a lot more time to think about our love affair. For example, what keeps it going? It seems like it’s some old energy left over from the creation that gets loose in us. But what’s outside it, god, I don’t even want to think about that. Sometimes at night on a silent highway the car dips down into a hollow. The people in the back seat making love whisper and draw closer. You throw your cigarette out and the red sparks explode an entire horizon of burning cities and violations and then just as suddenly it all goes black, and the car is carving into the night as the lovers go on about their business. Freedom, the carny show. Just then my quesadillas arrive. It’s a lacklustre performance, and I start having a fantasy about being the server’s pimp. I guess I’ve been thinking a lot about thuggery. Actually she just wants to drop off the check. I suddenly have this fear that all the tires on all the cars in the parking lot are going to jump off their axles and start rolling, crash through the glass windows and then through the booths. I sign the credit card receipt. Of course I’ve been thinking a lot about love too. We like to pretend that love has no boundaries. But what has thicker walls than a love story? I walk into the parking lot. The wheels are quiet. I drive home, returning to you.

***

That night we walk again on the velour path in the dim forest. The lane seems narrower this time. You don’t want to kiss as much. I’m wearing that fantasy of the pimp I had in the Chili’s like a chain-link maillot. We don’t see the man with the pug – the pugilist, ha ha. The lights are dimmer. The trees’ ramage looks sticky, like a web. The dim light is caught and dully glistens there. My kisses tonight come in the form of demands. I want to stop that, but I can’t.

We sit on a stone bench. This could be the 16th century. The physical is dissolving, or better thinning. When an old lady approaches us––she looks like Katharine Hepburn – I think she is a tarasque. She says: “I just walked down to the end.” I say: “Is it bad down there?” “Yes.” she says. “Very bad.” I say: “I heard there was some kind of log ride, like a theme park.” She says: “I wouldn’t exactly call it that.” And then: “Look at this,” and unbuttons the top button of her blouse and pulls out a tea saucer. “This is from the Royal Amsterdam. Just after the war. I will never forget how it rode into New York Harbor. We were all cheering, so full of life back then.” I say: “When life was still possible.” “Oh no,” she says, “it wasn’t possible then, either.” We politely excuse ourselves. We walk further down than we ever have. I’m still trying to figure out why she pronounced ‘rode’ as though it had two syllables. I don’t know whether we intend to go to the end. Of course, what does that mean anyway? Intend. We cross a rope bridge. This has the feeling of outskirts. There’s a talking antelope. It can only say three words: nettle, shine, deck.

A few steps on, just at the edge of the path, I see something and don’t know what it is at first. But I look again, and I need no procedure. It’s a woman of average height. She is leaning over with incredible delicacy over a smaller person, who I realize suddenly is a dwarf. The dwarf’s pants are around his ankles, and he is wearing a green felt hat with a feather, and she is fellating him. I try to shield you. I don’t want you seeing this. Don’t look, I start to say. It’s pornography, but then you grab my arm and say: “Don’t look, it’s very intimate.” It true. A gentle gossamer benevolence has transformed them. I’ve never seen such expressive fondness. For the tiniest instant I feel as though the heart of some other animal is beating inside me, and I want to admit to you that I never knew anything about pornography at all, but then I see some holy dazzle in your eyes. I let it pass. (I assume it’s the possibility of love.) We look upwards. In between the stars and treetops, bats are flittering. I suddenly ask you to marry me. You turn me down, of course. You say: “True love is a delicacy whose violence must astound us.” “Does it have to be so exquisite?” I say. You don’t answer, and we come to a fountain. There’s a guy who looks a lot like Westmoreland, the Vietnam general, and when the Katharine Hepburn woman arrives, I see they’re in a relationship. Some birds are pecking away at seeds that have fallen from gigantic humid frangipani blossoms. “If we’re not going to get married.” I say. And you say: “We’re going to get married. Just not how you think.” But I know too well how I think. One of the problems is that in this life you’re either a thug, or with the thugs (all the while pretending you’re not), or the thugs come after you. Nobody wants choice number three. The thug says, you’re going to sign the confession or I’m going to ram this stick up your ass. The thug adds, that’s not really even a choice.[1] And those are the civilized thugs. So what are we supposed to do? “The problem is deeper than that,” I say. “What problem?” you say. “I forget what we were even talking about.” And I say: “What I was thinking about.” And then I think, it’s the desire to make the other ones vile. Of course you’ll sign the confession, and then everyone will scorn you. Certain languages have a dedicated word to describe this process. Others have several near synonyms.

Meanwhile, you’ve gathered up the fallen seeds, and the sparrows are flying in a halo around you dipping into your hand. One of them is an especially proud and cocky fellow. I have the feeling he’s flirting with you. Various people looking like they were at a concert begin entering the plaza, and then musicians are arriving, some playing fifes and piccolos, and the guy on the alto looks like Ornette Coleman. Next come baton twirlers and girls in sequins like the Kilgore Rangerettes. And I glance and see the old lady, looking more and more like Katherine Hepburn, and she smiles and says: “We’re going on. It’s just a little further. Will you join us?” And I look at you and see the birds still fluttering in a crown around your head, and I say: “Perhaps we’ll catch up with you.” And we watch her go, she and Westmorland, and I turn to the fountain. The stonework looks like a plaster cast of the Trevi, something like they might pull at the Bellagio. I start to feel let down, but I still want to be here. I listen to the band. And then suddenly I see the connection, nettle, shine, deck, and how clever I think, or at least I think it might be, but then it disappears. And you look at me and say: “Pop music,” by which I know you mean love, and I say: “Pop music what?” and you whisper: “Pop music limns the boundary horizon for the market possibilities of oompah,” and then I think, and how exactly is all this supposed to end in the love affair? And then the band, with the piccolos handling the melody, starts playing something, and I can’t tell whether it’s In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida or the theme from El Topo. And that’s it.

[1]Actual reported speech. [/private]

About Peter Vilbig

Peter Vilbig is a writer and teacher living in Brooklyn, New York. He is a former journalist who covered politics, war, and refugees in Central America and later government, crime, and culture in Miami, Washington, D.C., and New York. His reporting from Central America appeared in The Boston Globe, and he was a staff writer for The Miami Herald. His short fiction has appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Baltimore Review, Drunken Boat, Fleeting, Horizon Review, The Ledge Poetry and Fiction Magazine, The Linnet's Wings, Saranac Review, Shenandoah, and Tin House, among other publications. He is currently completing a collection of short fiction.