You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Cassandra White is not a virtuous widow with her grizzled hair coiled into a bun. She does not wear a series of shapeless outfits in black, and she does not, ever, sit in a rocking chair surveying the scene with her rheumy eyes, saying, ‘Before my dear Harry died . . .’ or ‘In my day . . .’

Cassandra White is not a virtuous widow with her grizzled hair coiled into a bun. She does not wear a series of shapeless outfits in black, and she does not, ever, sit in a rocking chair surveying the scene with her rheumy eyes, saying, ‘Before my dear Harry died . . .’ or ‘In my day . . .’

She does not walk falteringly with a stick and she does not smell faintly of mildew.

She does not say ‘Oh dearie me’ when she stumbles.

In short, Cassandra White is not the delicate old lady I conjured as I read her advert.

[private]Really there’s very little way I could have expected her at all.

She is possibly the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen. She is six feet tall and she has a shock of orange hair, blood orange setting-sun orange, and when she marched down the drive to greet me it was flaming like a furnace on her head. She appeared with a beacon above her, saying, ‘Welcome, did you find it OK?’ She shot me a brilliant smile, as I stumbled out with my bags. A charming twist to her mouth. As I stepped heavily into the knee-high mud, she took a bag and carried it. And all the way into her house she was like a tour guide, ‘And this is where my grandfather built the second part of the house, and this is the oak outer door my parents put in, and this is where my mother used to keep her horses,’ and the whole layer upon layer of her family history, ‘and this is where my late husband always smashed his head, be careful now.’

She was like a country hostess who somehow remained oblivious to the fact that her country pile was really a dump.

Because it was clear, as soon as we went inside, that Cassandra White lived in the biggest dump I had ever seen. A dump beyond my worst imaginings. Not a small dump, not a cramped hovel by any means. There was plenty of this dump, room upon room, each one full of family heirlooms and mouldering clocks and sour old bits of furniture teetering on the ancient slate. There was the storeroom with dead meat hanging in rows and layers of home-made wine and jam and cheese and butter and barrels of home-made cider and the greenhouse and the toolshed and the cowshed, where there was a pile of straw and the lingering stink of a cow.

‘My last remaining cow,’ said Cassandra, with an angry nod.

And the unspeakable grossness of the dry toilet or, as Cassandra called it, the thunderbox. I didn’t know about that when I first arrived – Lord Jesus, how I didn’t know about that, and how I was soon enlightened – but I did observe that the kitchen was a place of damp-ravaged tiles and peeling wallpaper, with the shrill high smell of rotting matter and something else, something even worse.

I somehow doubted – glancing around again – that Cassandra had anything like a dishwasher. I doubted she had a Magimix or a microwave. And there was no sign of a set of matching dishcloths and a range of over-sized wine glasses and tasteful ranks of white crockery.

Indeed the inventory of Cassandra White’s kitchen would read:

Three chipped cups and a stained teapot, relicts of an ancient tea set

A mound of detritus

Some mould

A double-barrelled shotgun

200 mice

Three rats

‘Do have a cup of tea,’ said Cassandra White, taking a kettle from the stove and pouring water into a pot.

There was some fruit on the table. She had a generous broad local accent and she said ‘coop’ for ‘cup’. In her bony face shone her perfect teeth. Her cheekbones jutted beneath her sunken eyes, her skin was taut-translucent across her bones. Her eyes were green and they fixed on you, she just smiled and stared so finally I said, ‘Well, thanks for inviting me over. I don’t really know what I would have done otherwise.’

‘You fell on hard times, did you?’ she said.

‘Yes, essentially.’

‘Have a piece of fruit,’ she said. ‘It’s from the garden. I don’t have toast. I regard bread as a vice.’

‘What, because it’s a carbohydrate?’ I said.

‘No, because of grain. Grain is a hoarder’s commodity. An appalling thing. You hoard it and then you create armies to protect you and your grain. You create big surveillance towers to watch the grain. Those ancient grain cities thousands of years before Christ, that’s what happened to them. A big tower, full of soldiers, with an eye on the top, watching everyone.’

‘Really? So because of the ancient cities you don’t eat bread?’

‘Because of the evil effects of grain in general.’ ‘OKAAAY,’ I said, while thinking, About TURN! QUICK MARCH! EVACUATE EVACUATE!

‘I don’t like much of what I see around me,’ said Cassandra. ‘So I live here and keep my head down, and try to fend for myself as much as I can.’

‘How long have you lived here?’

‘My family’s owned this farm for hundreds of years. We’ve been in this valley for thousands of years, I reckon. My parents only had girl children, so I inherited the farm. I was the farmer and then when I married everyone called me the farmer’s wife. My husband wasn’t a farmer at all, though. He was in the army and he was blown up in the desert. Then foot-and-mouth destroyed this valley and when they had slaughtered all my cattle the government offered me two cheques. For my husband and for my cattle. I couldn’t take either. So I sold most of my land. I’ve a couple of acres left. Everyone else took their cattle money and bought up my land and my farm fell apart.’

‘I’m very sorry to hear it.’

‘It’s not important.’

‘Of course it is. It’s terrible.’ And I was sorry for her. She lived in a slum and her husband had been blown across a desert. Then in a fit of pique she had shafted herself entirely. It was hardly as if she was having a really fun time.

Her house felt as if a high wind would tear it to pieces, drive it back across the fields. On the stove a vat of water bubbled and steamed. ‘I don’t generate enough electricity for a kettle,’ she said.

When I had finished my tea, she stood up and said, ‘I’ll show you around a bit.’ So she marched me out of the kitchen into a draughty dining room, with a grand oak table and a few drunken chairs. A clock chiming in the background. A big portrait of a man in a frock coat.

‘My great-grandfather,’ said Cassandra. Glaring down at her, wondering what the hell she had done to his farm.

‘Mmm,’ I said, as my limbs ached with the cold. Then a frigid living room lurking under oppressive

beams. Some armchairs with their stuffing spewed out. A big smelly rug. ‘You have dogs?’ I asked, already knowing the answer.

‘Yes. They’re in the yard,’ said Cassandra.

‘Great,’ I lied. ‘I love dogs,’ I added as if I hadn’t lied enough. She gleamed a smile and tossed her mane.

All the way up the stairs, her ancestors glared down at us, cold-faced and angry, and there were two more recent portraits, in pen and ink.

‘Who are they?’ I asked.

‘My children,’ she said. ‘Jacob and Evelyn.’

‘What do they do?’

‘Oh, it’s very sad, I love them dearly but they’re both completely insane.’

‘Are they in an institution?’

‘Both of them, yes. Jacob is a management consultant in Sydney and Evelyn is a trader in New York. They don’t talk to me any more.’

‘But they have a history of mental illness?’

‘No, no, that is their mental illness.’

‘That they think they’re a management consultant and a trader?’

‘That they ARE a management consultant and a trader.’

‘Okaaay,’ I said.

We turned along a corridor and there was a bathroom with an ugly iron bath and a chipped sink and curiously enough no toilet, and some big cold bedrooms, each with a venerable bed, a few landscapes on the walls, their colours bleeding away, an oversized dressing table, some china.

‘Fortunately for me this house was built to last,’ said Cassandra. ‘Keeps the rain off my head. Stops me freezing in the winter.’

‘Charming,’ I said.

Cassandra White has stripped her life of frills and comfort. Her house is an unsettled pile of slate, neglected and shambolic. She doesn’t even seem to notice. She holds her head high. Her arms are sinewy. Her shoulders are broad and padded with gristle. She has creases around her eyes, ingrained furrows from staring into the sun. She has still more lines drawn deep into her forehead. Her hair gets into her eyes and she blows it out again. She wears the same pair of old cords every day and the same blue jumper. She has a big pair of muddy wellingtons and a battered wax jacket. She stalks across her dwindled stretch of land and she grabs goats and hurls them around. Every day she works, to bring in water and light the fires and shovel shit and milk the goats and collect grey water or rainwater or whatever sort of water it is, just not mains water lest she be afflicted by plague or ebola or drugged and rendered compliant or whatever it is she’s worried about.

We were almost friends but then she showed me the thunderbox. After that I couldn’t forgive her for a long time. We were crossing a yard and before us was a little wooden hut with a door halfway up it, and steps leading to the door. There were two chimneys coming out of the roof. In my naivety and optimism I thought, ‘How delightful, perhaps I could use it as a study, a cosy little study where I will be able to pass the mornings reading,’ and then as we approached I became aware of a strange musky fetid aroma coming from the place, a wafting earthly stink of matter, MATTER.

Disgusting, I thought. An outside toilet. How unnecessarily vile.

But this was no ordinary toilet.

This was a thunderbox.

A thunderbox, Cassandra White explained to me, was the invention of a man who was clearly insane. This man decided that there was simply no need to flush your shit away, and instead you could more naturally and more charmingly store it in a massive pile in a chamber under your toilet.

‘It’s absurd that we use animal manure but not human manure. It’s just squeamishness, we don’t want to accept that we are also beasts. Anyway flushing your waste pollutes available drinking water and also wastes all the nutrients within the waste,’ said Cassandra.

‘It also stops it sitting in a big pile under your toilet,’ I said.

‘That just dries out the waste and then every so often you pat down the pile of waste under the toilet. It’s a two-chamber system so eventually you transfer to the second chamber so the first chamber can compost down. That takes years though, as long as you pat down the pile. It’s not as if you’re shovelling it out every weekend. Then eventually when it’s all composted you put it round the fruit trees in the garden.’

‘You actually put it on your garden?’ I said, thinking of the fruit I’d just eaten.

‘Of course. It’s great compost. Anyway obviously there are some different rules with a thunderbox so it’s best if you don’t piss down the toilet, piss is no good to anyone, so piss in this bucket instead, and don’t put too much paper in the thunderbox, and always pour some sawdust down after you’ve finished, and close the lid afterwards, so you don’t get flies in there. Flies love the damn thing, of course. I also put a lot of waste from the kitchen and garden down there, just to keep it all moving along.’

For a moment I thought she was toying with me, and there was actually another toilet elsewhere, a whopping toilet with a lovely whopping flush, whisking everything away before you could say ‘Crapper’. But no, it turned out there really was this thunderbox and a bucket and a shovel, and a set of rules which made my stomach turn and do a crazy waltz just to read them.

It’s curious how the presence of such a thing, such a phenomenon, causes you to think anew about everything.[/private]

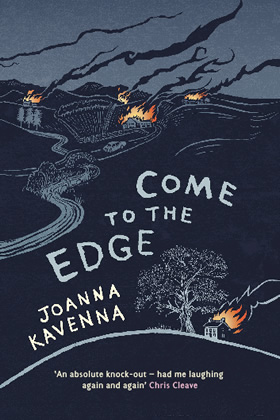

Come to the Edge will be published in the UK by Quercus on 5 July 2012 (hardback, £12.99).

About N/A N/A

Joanna Kavenna grew up in various parts of Britain, and has also lived in the USA, France, Germany, Scandinavia and the Baltic States. Her first book The Ice Museum was about travelling in the North. Her second was a novel called Inglorious, which won the Orange Award for New Writing. It was followed by a novel called The Birth of Love, which was longlisted for the Orange Prize. Her latest novel is a satire called Come to the Edge. Kavenna's writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the London Review of Books, the Guardian and Observer, the Times Literary Supplement, the International Herald Tribune, the Spectator and the Telegraph, among other publications. She has held writing fellowships at St Antony's College, Oxford and St John's College, Cambridge.