You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

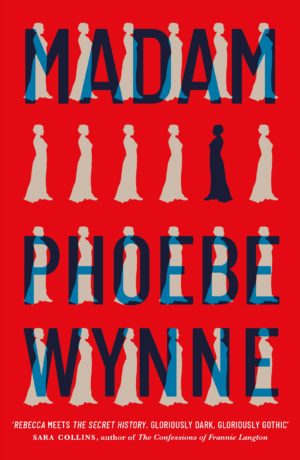

Phoebe Wynne’s Madam charts the experiences of a young teacher who joins a prestigious girls’ boarding school in the UK, only to discover that things are not as they seem. She meets an overbearing enemy, and unable to confront it herself, she must recruit the girls around her to bring about its defeat.

Phoebe is a Classicist and spent several years teaching in the UK and in France before leaving the classroom to concentrate on her writing. She now spends her time between both countries. Madam, her debut novel, is released today by Quercus Books.

In this feature, Phoebe meditates on the writing life and some of the episodes that have brought her to this point.

.i.

Three years ago I left my teaching career behind with one aim – to have a proper go at writing. I had already written two miserably bad novels in between school terms, and I realised that if I really wanted to achieve something, I needed to learn my craft and give myself time, quiet, and focus. I felt like a pregnant woman unable to give birth, an uglier and unhappier version of Sylvia Plath’s “there is a voice inside me that will not be still.” A teaching colleague had tacked onto her office noticeboard a different quote, which shone out to me every day like an accusation. It was Seamus Heaney’s “the way we are living, timorous or bold, will have been our life.”

I considered giving myself one year; I collected my savings, put my things into storage, moved in with family, sat down, and opened my laptop.

What I didn’t realise was that by leaving my career, even as part of a one-year plan, I had broken an unspoken covenant. The people around me saw this act as a mistake – an insult, even an insolence. I discovered that those I knew had happily placed me in a box: teacher, academic, server of others, and I had somehow signed a societal contract to stay in said box and stay in my place while doing so; but I couldn’t and I wouldn’t. A family friend, whose late husband had taught me as a child, told me I was a “rotter” to have given up the worthy and esteemed role of head of Classics at one of the top schools in England. I can still feel the horrified tone of her rebuke.

I hadn’t realised that on a grander scale, I had broken away from the establishment and had somehow betrayed my roots and dishonoured my collective. The society I came from was a class-based patriarchal one, where I’d learned that my value lay in being academic, pleasing, and achievement-driven. I’d strived to attach myself to something significant, something others would recognise, like an excellent and celebrated academic institution. In a society where humans are “doing” rather than “being,” I’d broken away, rudderless, floating towards an unknown and unseeable land that might not even exist. The weight of disapproval was heavy and stretched from my parents’ generation to my siblings to some of my closest friends; it was a difficult several months under their hot, judgemental gaze.

With my mind free of lesson planning, report writing, department meetings, faculty meetings, emails from teaching staff, boarding staff, and parents, I finally had the freedom to clear my head and find my story. Yet the further I drifted, the more I observed the spot I’d left behind. It was ugly, an eyesore – but full of colourful characters, conflict, and many things to say.

Leaving those institutions – and by that I mean the school, society, and England – allowed me to break free. I have never been more terrified yet so determined in my life. Exorcising the very thing I had needed to escape, exposing it or seeing it truly, became my story. I suppose we have to abandon things to really see them as they are.

.ii.

During my year of writing, I found myself in Los Angeles tagging along with my sister’s family on a three-month film project. The land of visual storytelling surprised me with its warmth – the people as well as the weather – and I signed up for writing classes. The first was a prompt-driven workshop on Sunday afternoons in Laurel Canyon, the second was a skills-based seminar on Thursday nights in Los Feliz.

I threw myself into learning how to write, I bought the best books, scoured and devoured them, tore them apart for their secrets. I practiced and flexed my writing muscles every day and did my homework for each class: like a violinist learning her fingering and hand positions, eager to improve, getting ready to perform a concerto and play out her heart.

The Sunday afternoons were a balm. Around eight of us sat up straight in thick armchairs dotted about a woman’s sitting room, and smiled awkwardly at each other. We waited for the prompt, then threw our pens across the page. Fifteen minutes later we read aloud our attempts at writing and critiqued each other, kindly. My initial agony dissipated over three months, and I learned my first valuable lesson: how to give feedback and how to take it. The Thursdays were technical, tool-sharpening, and repetitious, a small number of us gathered around another sitting room, discussing, debating, and working hard.

The best thing about those writing classes was the students. I’d never met people like that before: warm, encouraging, listening, interested, open-minded – American. I found kindred spirits in those colourful fellow writers. Everybody was excited, everybody wanted to go somewhere. Back at the house, too, my sister’s friends, her husband’s friends, were constantly “making.” I learned that it’s fun hanging out with people in the film industry when you’re not in the film industry, because you can’t talk shop, you can only talk ideas. For the first time in my life, I was surrounded by creatives rather than academics, and I liked it.

It’s certainly true that my Englishness set me apart from the others – Wow, a boarding school? Oh, she teaches Latin? No! There are cliffs and the sea crashing against them? And ancient women involved? Sounds great, I’m in. The Californian culture of encouragement pushed me forward, and my early ideas turned into thicker chapters and a refined plot, and sparked a blazing fire inside my chest.

When I got back to England months later, my enthusiasm for writing classes chased me into two more in London. I chose the same pattern: the first prompt-based, the second more technical, but I never expected my writing fire to be hit by a cold blast, just like the weather, on my return. My bold ideas were shaken, my plot picked apart, and the remainders were dismissed. A boarding school – What’s new about that? Feminism – Wasn’t that over in the 70s, we have equality now! A tragedy – Oh no, there’s a new trend for “uplit” now. I heard their chorus loud and clear: We don’t want your gothic boarding school drama here.

Each week left a bitter taste as I travelled up to London on the train full of anticipation, poring over my miserably annotated pages on the way back, shaking my head against the sharp and unkind remarks. Nevertheless I persisted and attended every class, learning how to filter the criticism and sharpen my writing, ready to slip into some manic alone time in the early summer to finish my first full draft. I returned frequently to my American pages, stared through them, and Madam fell out, loud and ready. Thank God I’d tried the American writing classes first.

.iii.

The world is your oyster, we were told as teenagers. What do you want to be? You choose! Put the work in, and it will all become yours.

I don’t think I can condemn the careers advisor at my overprivileged boarding school – I’m sure advisors in schools all over the UK were saying the same thing, filling out forms for hordes of student, and pushing them in various neatly allocated directions. We were fed the traditional diet of achievement equals high grades equals happiness. Want that? Tick this box, jump through this hoop. Academics were the thing. My sister wanted to be an artist but went on to study Philosophy at Reading. I pursued Classics rather than English, not only because I was good at it, but also because it was a niche subject with fewer students and gave me more of an “edge.” I earned my all-rounder scholarship every day of the week; I studied the mark scheme, I wrote essays full of words, and won sparkling, empty grades.

Ten years later I horrified myself by brandishing the same mark schemes at my own students, telling them that if they’d play the game, they’d get where they wanted to go. Unexpressed creativity is damaging. My sister, by the way, now works in costume for film and TV, so the Philosophy degree didn’t help her much – and neither did her student debt, which she’s still paying off, as I am mine.

My generation of millennials has apparently struggled to reach our “potential,” since of course we prefer buying avocados to paying off any mortgage, when in fact the truth is we haven’t earned enough for a deposit on a house. None of my peers seem to have risen to this great bar set for us, and instead we hobble in the gutter, battling our imposter syndrome. How can our potential be measured? Yes, we decorated ourselves with good grades, but hadn’t we been instructed how to get them? Yes I was a good teacher, but wasn’t it because I’d been trained particularly for it? Who was I, beneath that training, that discipline?

What I really wanted was to be a writer, a novelist – the kind of job that everyone thinks they can do but very few are lucky enough to realise. So I settled myself into teaching. I enjoyed the safety of academia, routine, the sparky students, every day never the same – and, more importantly, knowing that the profession rested on qualifications and would secure me a regular salary and perhaps even a place to live. I enjoyed that brilliant ordinariness for eight years, but all the while the writing bug niggled at me. It’s true that a contented person never changed the world, so I changed mine.

When I got my book deal, I thought, That’s it, I’ve made it. I must be a decent writer or my agent wouldn’t have taken the book on and the publishers wouldn’t have grabbed it with both hands. Or have they made some terrible mistake – no, the contract was signed. My inner careers advisor was both thrilled and appalled, his boxes ticked many times over now that I had achieved this extraordinary thing. This oyster pearl they’d dangled in front of us – hadn’t I caught it? Not quite, for then came the next necessary achievement: edits, copyedits, proofs, feedback, reviews, how the book might do – all lining themselves up like a terrifying band of unruly children that had to be disciplined. I’ve managed to tick them all off for Madam so far, but of course the expectations have been refreshed with my second novel.

It is true to say that my creativity now earns me a living, and that perhaps I have taken a higher step in many people’s eyes. But even as I spend many days alone typing at my laptop, I remember laughing moments in the classroom, in the dining hall, in the boarding house. I remember so much of it so fondly that I filled my first novel with students’ voices. I wouldn’t go back, I wouldn’t change this path I’ve taken, but it’s certainly true that some moments I took for being ordinary were entirely striking and unique.

So I’m forced to accept that none of us are extraordinary – we are all beautifully ordinary. There might be no oyster pearls for the world to offer us, and that’s all right. I just wish I’d been able to report this discovery back to my students. Tell them that the things we’re chasing after might not even exist, and perhaps it’s enough to turn what is into what could be.