You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

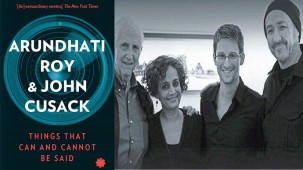

Go shopping I recently picked up a copy of Things That Can and Cannot Be Said – a series of essays and conversations in which Booker-prize winning author Arundhati Roy and John Cusack, actor and filmmaker, talk about their meeting with NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in Moscow. Roy and Cusack touch upon many topics including the meaning of nationalism, the nature of war and empire, the culture of surveillance in modern times, and the barriers that prevent the free movement of people in an allegedly globalized world. The book, an engaging and essential read, got me thinking. Who lays down the law about that which can and cannot be said in public? Who decides what a writer can speak/write about?

I recently picked up a copy of Things That Can and Cannot Be Said – a series of essays and conversations in which Booker-prize winning author Arundhati Roy and John Cusack, actor and filmmaker, talk about their meeting with NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in Moscow. Roy and Cusack touch upon many topics including the meaning of nationalism, the nature of war and empire, the culture of surveillance in modern times, and the barriers that prevent the free movement of people in an allegedly globalized world. The book, an engaging and essential read, got me thinking. Who lays down the law about that which can and cannot be said in public? Who decides what a writer can speak/write about?

The practice of raising objections against a book’s contents is as old as time. Calling for an official ban on the book and effectively placing a gag order on the writer follows suit. An exhibit organized by the American Library of Congress titled, “Books that Shaped America,” is an eye-opener. Of the books featured in the exhibit, a disproportionately large number have been banned or challenged since they were written. These are books most of us love and have read (and keep re-reading). We would definitely cart them off with us if we were to be marooned on desert islands. The list is long so I’ll pick a few.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was first banned in Concord, MA in 1885 and berated as “trash and suitable only for the slums.” Complaints have been filed over the years against Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, Beloved, blaming the novel’s sexual content, depiction of violence, and references to bestiality. The Salinger classic, The Catcher in the Rye, has been banished from school libraries more than once on charges of being “negative,” “blasphemous,” “obscene” and “filthy.”

Ernest Hemingway’s tragic tale of war, For Whom the Bell Tolls, was deemed non-mailable by the US Post Office in 1940, the year the book was published. Needless to say, the Post Office was playing censor when it made the decision. In the 70s, eight Turkish booksellers were rounded up and tried for spreading anti-state propaganda. Their crime – publishing and distributing Hemingway’s novel.

Melville’s Moby Dick (1851), Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) – have all invited charges of “conflicting with community values” and “obscenity” since the date of publication. The fact that these charges continue to surface proves that despite the passage of time, very little has changed when it comes to misusing literature as a tool for moral posturing.

Books – and writers across the world – have suffered much hardship at the hands of religious zealots. The most publicized instance is the ban on Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses and the fatwa issued against him by the Ayotollah Khomeini of Iran in 1989. The novel was banned in several countries. India was the first to ban it in 1988. Curiously enough, 27 years later, a former minister in the Indian government admitted at a public forum that the ban had been a “mistake.” Rushdie took to social media to respond. “This admission took just 27 years,” he tweeted. “How many more before the ‘mistake’ is corrected?”

In 2010, a conservative right-wing Hindu group in India launched a legal battle against scholar Wendy Doniger’s book, “The Hindus: an Alternate History.” The group pounced on Doniger and accused her of insulting Hinduism by describing the sexual desires of mythological figures in her book. Doniger expressed concern about the worsening political climate in India and the curbs on free speech. In the end, her publisher caved in and agreed to pulp existing copies of the book and to bar it from India to keep the peace.

A few months ago, Perumal Murugan, a well-known Tamil writer from southern India was forced to file an apology and to withdraw his book, One Part Woman, from stores because a far-right Hindu group found it “obscene.” Death threats were issued to the writer and his family. Mobs burnt copies of his book in public. A frustrated Murugan decided to stop writing and declared that “Perumal Murugan the writer is dead.” It took a landmark judgment by Justice SK Kaul of the Madras High Court to resurrect Murugan. The judge refused to ban Murugan’s book and requested him to get back to what he does best: write. Justice Kaul’s advice to rabble rousers: “If you don’t like a book, throw it away.”

About Vineetha Mokkil

Vineetha Mokkil is the author of the short story collection, "A Happy Place and Other Stories" (HarperCollins). She received an honorary mention in the Anton Chekhov Prize for Short Fiction 2020 and was shortlisted for the Bath Flash Award in 2018. Her fiction has appeared in Gravel, the Santa Fe Writers' Project Journal, Cosmonauts Avenue, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, and "The Best Asian Short Stories 2018" (Kitaab, Singapore).