You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

For a long time, I didn’t confess to the wider world that I was a writer. It wasn’t until my first novel was bought by a publisher and I’d actually signed the contract that I decided to really come clean. Even after that, with certain people, I didn’t say anything until the book was physically on the shelves. The reasons I was cagey about it were manifold. Firstly, it’s a long road and it takes a considerable length of time to produce anything one feels comfortable letting people who aren’t your best friend or your mum see. Even your closest allies get bored of waiting for you to publish, bored of hearing that you’re still working on the same story you were working on the last hundred or so times they saw you. They either want an excuse to break out the bubbly or they want you to shut up about your book. It’s a bit like listening to someone talk about their marathon training, and for years rather than months at that Bor-ing.

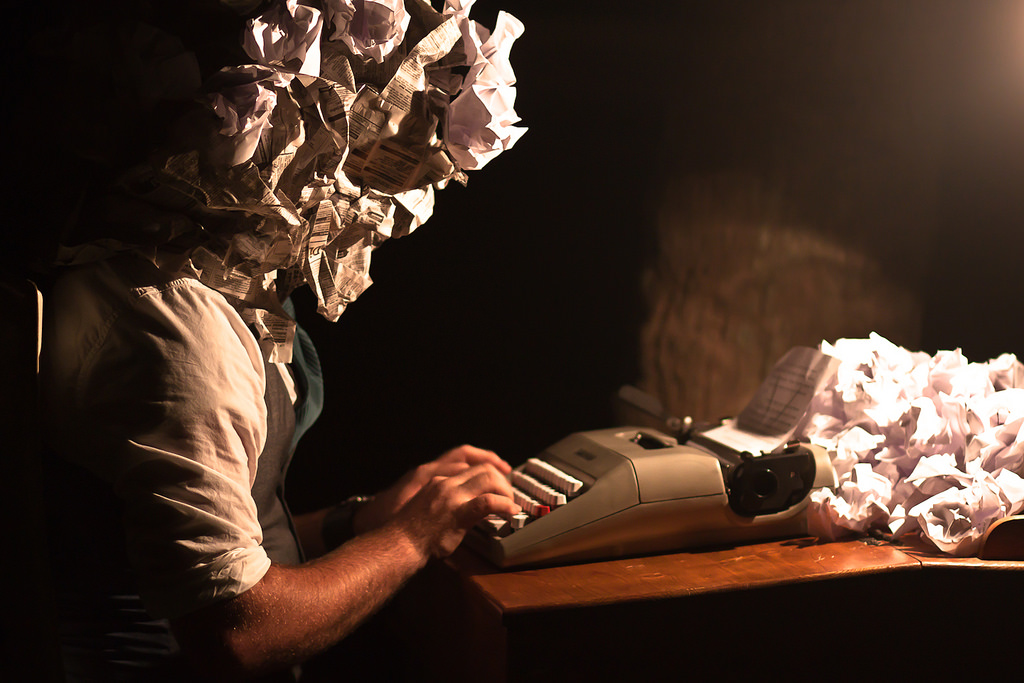

The second reason and probably the biggest is that I got fed up of the thinly disguised smirk that my confession was often greeted with because, you know, everyone’s a writer. Or at least it seems that way, as if everyone who can’t wield a paintbrush or play an instrument with any degree of competence toys with the idea of writing a book because writing is a paint-by-numbers and keep-within-the-lines kind of thing, isn’t it? I’ve lost count of the times I’ve heard someone say, ‘I wanted to write a book too, but…’. Most of those people, for various reasons, never will: it takes too long, it’s too risky, you only get paid once it’s done and rarely earn a fortune, one might as well expend one’s energy doing something more practical etc etc. The sorts of people who don’t do it for those reasons were never really going to be writers anyway because writing isn’t a lifestyle choice, it’s a compulsion.

Though being a living-on-a-shoestring, aspiring author might seem cool in your twenties, it becomes just plain embarrassing if you’re actually living on a shoestring and still aspiring in your forties. By the time I’d finished my long uphill apprenticeship and the first book was ready to go, most of my fellow writers had long since fallen away. People who are really writers know they are writers. They know because the thought of not writing is unbearable, because they are like withdrawing addicts when circumstances prevent them from writing, because writing is when they feel authentic. From the outside, who can tell who is genuinely a writer and who isn’t? So I suppose the slight smirk is understandable.

Negative reactions are also sometimes from people, usually close friends and family, who can’t bear the thought that you might be wasting your life chasing an impossible dream. People who are genuinely concerned about your future wellbeing and just wish you’d buckle down and make something of yourself. My Dad once said to me, ‘I know you’re bright so I don’t understand why you haven’t really got very far.’ He didn’t mean ‘got very far through the book’, he meant ‘got very far in life’. Needless to say, I have siblings who have more letters after their name than I have in my name.

Like most people I was raised to think that the summit not the climb is the point of any endeavour. Of course, I do not believe that now. I now believe that a person is the sum of their experiences, not of their achievements. Something I’ve noticed in the biographies of many writers is that their employment history is often eclectic, characterised by a kind of restlessness. This might be taken by some as a lack of commitment to a ‘proper’ career but I don’t believe that is so. I think it’s more to do with a kind of hunger for experience coupled with a need to find some kind of ‘home’. I suspect that most writers feel like misfits and that home, rather than being a place or a group of people, turns out to be within language.

Of course even when your book is finally out, the reactions aren’t always salutary. For someone whose creative progress has stalled because of fear, bad luck, lack of commitment or frankly, in some cases, a lack of genuine ability, it can be hard to watch someone else take a risk and then have the temerity to succeed.

Writers, like any artists, are wise to start growing a hide like a rhinoceros and to start growing it early. Because even when you get your book onto the shelves the negativity doesn’t stop. Some readers will genuinely appreciate your work but others will take delight in savaging it. They assume, like many, that if your head is above the parapet, it’s okay to take a pot-shot at it. If you’re the sensitive type, (and sensitivity is part of the artistic constitution), other people’s negativity can be creatively disabling.

One of my favourite antidotes is what I call my medicine bundle. This is a tatty file full of anything that has made me feel good about my work over the years or reinforced my reasons for doing it. So in my medicine bundle I have printouts of positive reviews, feedback from course tutors, the very first letter I received from my agent inviting me to get in touch, encouraging cards from friends and family, quotes from long dead writers. A medicine bundle should have no room for the ambivalent or the begrudging, only for what is resolutely positive. It’s basically a psychic hug stored up for when I need it. And there have been plenty of times when I’ve needed it to remind me that my work does have merit and that other people that seem quite sensible and that I don’t owe money to think so as well.

About Niyati Keni

Niyati Keni’s first novel, Esperanza Street, was released by indie literary press, Andotherstories, in February 2015. Described by Kirkus Reviews as a ‘luminous, revelatory study on the connection between person and place’, Esperanza Street is set in a small-town community in pre-EDSA revolution Philippines. Keni studied medicine in London and still practices part-time as a physician. She has travelled extensively within Asia. She graduated with distinction from the MA Writing at Sheffield Hallam University in 2007. She is now based in the south east of England where she is working on her second novel.