You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

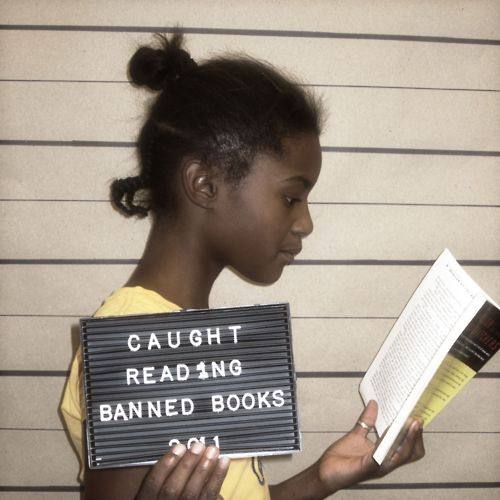

D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Henry Miller, Tropic Of Cancer. William Burroughs, Naked Lunch. All famously censored. Banned. They’re Penguin Classics now. Read by each new generation. At the time they were considered the works of perverts, of seedy letches. Had they been released today they may well have been sold in sex shops, with accompanying board games. This does not mean however that contemporary writers have free rein. For many there are still things you can and cannot say.

My first experience of this was rather mild. A lecturer informed me that my writing was too bleak for their liking. It was suggested I try a different, lighter, kind of reading, to open up my mind, to help me become more well rounded. I tried defending my right to literary despair, but was told in no uncertain terms that modern literature was no place for Nihilism, and hopelessness.

The second experience was an altogether more vitriolic one. My part was that of bystander. Sat on the sidelines quietly observing. As classmates, keen, made preparations for the literary magazine. Everyone provided something. Poetry. Essays. Short stories. One particular piece though caused considerable, and heated debate.

Centring on a much-publicised case of child abduction and murder, the story in question was set some years after, when the child, now an angel, comes down from heaven. Visiting his mother, who has regularly been appearing on national television, he implores her to stop campaigning in his name, so his soul might rest in peace. Of course if I were to tell you that some members of the class were offended it would be an exercise in understatement. Many staunchly refused to have it included. The lecturer looked utterly bewildered, unsure exactly how to proceed. The writer though remained resolute. Stalemate ensued.

I have no idea if the piece made the final cut. Looking back on it I suspect the main problem was the same one the censors had with the works of Lawrence, Miller, and Burroughs. It challenged the beliefs of the class. It was unapologetic in its stance, and in this case transgressed well beyond what was considered the more accepted ideals of literary principles. Nowadays we mostly laugh at the authoritarian views that judged the novels of the past. With a vague sense of superiority, we celebrate our time as something better, more informed. This doesn’t mean that literature no longer manages to cause outrage, and challenge the boundaries of what we consider acceptable. It is just that the reasons for offence have changed.

Take as examples Brett Easton-Ellis, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and Michel Houellebecq. Three internationally acclaimed writers who have enjoyed considerable success. And yet between them they have been accused of objectifying women, misogyny, and even inciting religious hatred. Now in the case of Easton-Ellis it is often argued that his offending novel, American Psycho, is one the of the 20th century’s greatest pieces of satire. I myself have written of the works merits when considered as an attack on consumer culture. But to deny that the novel contains shocking acts of violence would be ludicrous. The sale of the book is still heavily controlled in some countries due to its highly explicit content.

Excessive acts of violence though can often be found in some of Crime Fiction’s most popular titles, I can’t recall however an incident where there’s been a demand for the books to be banned. I realise this comparison may be problematic for some, as a lot of Crime Fiction focuses on a process of apprehension, and eventual justice. They’re thrillers, with a catharsis. American Psycho on the other hand revels in a harrowing ambiguity. Not so much crime and punishment, more crime and enjoyment. Perhaps though that is the point. Perhaps the novel acts as a representation of how societies everyday madness continues with impunity. Easton-Ellis himself has rarely spoken of the controversy that surrounds his novel, and the book remains, twenty years after publication, a divisive example of literatures ability to provoke.

Where Easton-Ellis greeted his critics with silence though, so Karl Ove Knausgaard has tried the opposite. Having first courted controversy due to the of name of his career defining My Struggle cycle, Min Kamp, in its native Norwegian, which is the same as Adolf Hitler’s autobiography. Knausgaard has since to defend the ethics of highly personal accounts of his father’s alcoholism and subsequent death. Most recently, as translations of the series reach fourth instalment, Dancing In The Dark, Knausgaard has had to address accusations of objectifying women. He has done this not with blanket denial, or apologetic placation. Instead he had defended his right to depict life as he sees it. Arguing that by writing what you can’t say, what you shouldn’t say, he is opening up more interesting topics of discussion, while simultaneously challenging hypocrisy.

In fact the freedom of artistic expression is an argument that has long been used by writers forced to defend their works. It is certainly one Michel Houellebecq has used throughout a career dogged by claims of misogyny, plagiarism, and even saw him charged with inciting religious hatred. He was never convicted. The judge eventually ruled that Houellebecq was exercising a legitimate right to criticise religions. The controversy that surrounds Houellebecq and his work though, particularly his latest novel, Submission, has only further enforced the question that just because a writer can say something, does it mean they should? Is there not a responsibility to respect other people’s morals and beliefs? Or is it a writer’s duty to challenge them?

Interestingly none of these controversies have hindered sales. In fact in most cases the furore has only enhanced author credibility, or notoriety, depending on how you look at it. This was certainly the case where Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was concerned, and more tellingly with the example of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. Having already rejected Burroughs manuscript on two occasions, it was not until the US Postal Service began to seize literary magazines publishing excerpts, for reasons of obscenity, did French publisher Olympia decide it would instead go ahead with publication. Coincidentally Olympia had already made Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Tropic Of Cancer bestsellers.

Of course this piece has merely scratched at the surface of why writers globally might find themselves banned, or censored. In so many countries today there are political, social, and religious forces that look to suppress writers, artists and musicians. So I cannot emphasise enough my admiration for the thousands of men and women who work in genuine fear that their art may lead to imprisonment or even death.

In a society such as ours then, that defines itself by its beliefs in freedom of speech. Where there are platforms for the opinions that offend us to be challenged, and shown for what they are.

I believe the focus should not be on what can’t be said, but what we feel has to be said.

About Reece Choules

Reece Choules is a regular contributor to both Litro and The Culture Trip. He lives and works in South London.