You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

What makes a writer? Their gender, their race, their social class? I’m not sure in all honesty. I don’t know what they are supposed to define, or represent. I’ve never thought about it to any great length. One day I sat down and started writing. Was it poetry, fiction? I don’t know what you’d call it. There was no great goal in mind. Satisfaction came from the act itself. When the notebook was filled I destroyed it. Years later this aimless action now has form and structure, but the force behind it remains the same. A desire for expression.

Looking back on it my life was much simpler then. I worked at Homebase, something I’d eventually do for eleven years, I came home, read for a few hours, watched a film, and then went to bed. Gradually this changed to working during the day, writing all evening, then reading before bed. I wouldn’t say I was happy with this arrangement, comfortably numb would be a more appropriate, if not Pink Floyd borrowed, description. Indeed if it was not for the intervention of a friend, in all likelihood, this routine would have continued indefinitely.

No one in my family has ever been to university, and before my friend ordered a prospectus for me, no one in my family had much thought about it either. Even after the possibility of going had stirred a yearning for something more, it took a lot of convincing for me to actually follow the route of further education, let alone in Creative Writing. I left school with GCSE’s in English, English Lit, History, Drama, and Religious Education. I had no A-Levels though so we wasn’t actually sure I’d be offered a place. In the end I was required to send the university a selection of my prose and poetry, which my friend had to type up for me, I didn’t have a computer. Then we waited. Fear crept in, doubts. Every other day I changed my mind.

When I eventually started the course I quickly realised how I was required to start thinking about writing in a way I wasn’t sure I was capable of. I felt I’d made a huge mistake. There was so much about the context of a work, about a writer’s life, and how it informed what they wrote. Everything ended in ism. Realism. Existentialism. Modernism. Post-Modernism. All somehow overlapping, with definitions that were not entirely clear, or in some cases, at least to me, accurate. To me a writer was a writer, all other considerations were just theorizing.

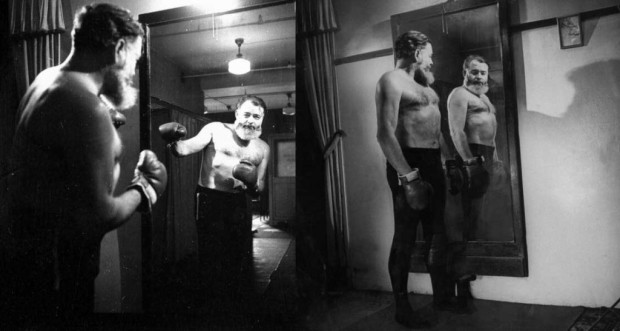

Reading essays from that period I notice how often I spoke of my affection for the work of Charles Bukowski. Post Office and Factotum, were, and perhaps still are, the only books I’ve read that represent a way of life I’m familiar with. Working for minimum wage, living with poverty, I could go on, I won’t. His influence is also notable in the prose I wrote at that time. Short stories such as Classic Writer Prize Fighter, which begins with a boxing match between Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, were a kind of Bukowskiesque riff on The Colour Of Money, and noir fiction. A novella, Ballad Of A Thin Man, detailed my time working at Homebase, and my youthful lessons in love, with all the raw intensity I could muster.

I’m thinking about all this because I find myself back in the family home. Staying at my mother’s while finishing my MA portfolio, and a few other things with their deadlines approaching. In quiet moments I take the books from my shelf bought by old lovers. I read the inscriptions in Notes Of A Dirty Old Man, and Ham On Rye. I read their introductions. Bukowski was the laureate of American low-life, of the drunks, and prostitutes, and barfly’s of LA. The back cover blurbs sell him as the down and out raconteur. Reading other blurbs, other introductions, I’m surprised by just how many writers are wrapped up in a series of meaningless labels, and taglines. Some of which work for the author, others which somehow demean their efforts.

If all my early writing was published tomorrow I suspect I’d be labelled a ‘working class writer’. The blurbs might say that I explore the tougher side of life in London suburbs. The heartbreak of disillusioned youth. My stories would be coming of age stories. Introductions of future editions might discuss how I was raised by a single mother on welfare. It might go into further details about nervous breakdowns, drug abuse, and my unfulfilled desire to be a musician.

Was any of this on my mind at the time of writing though? No. Was it what I was looking to dissect, and explore? No. I was lovesick. Like Goethe’s Young Werther I was a sensitive and romantic young man driven to despair. Once my circumstances changed though, so did my writing. My interest now is in the intricacies of long-term relationships, of reaching the age of reason. I’m fascinated by the influence of the state, and corporations on modern life. Would future theoretical works be judged on these hypothetical ‘working class’ novels of my past? Would I be accused of forgetting my roots, of not tackling the issues that still affect others like me?

Not so long ago I read an article by Taiye Selasi, author of Ghana Must Go, exploring the pigeonholing of modern African writers. It also discussed what makes a so called African novel, or indeed an African writer, and how there is an increasing struggle to define it. Going further Selasi lamented how she and her contemporaries often find themselves in a no win situation. Where if they write about the poverty, and war, that cripples many of their respective countries, they are accused of ‘poverty-porn’, and if they write about life or subjects outside of Africa they get accused of writing for the West. What I thought was perhaps most interesting about Selasi’s piece though was her taking to task this idea of the African writer as native informant. Arguing that African writers write for the love of literature and craft, just like any other writer.

Taken further this logic could be applied to any writer marginalised, and pre-judged because of their gender, race, class, or sexual preference. Of course all forms of diversity should be embraced, but not to the point where it detracts from the writers talent, or body of work. We should encourage those who seek to challenge prejudices, who write for equality, and social justice. Their subject matter should not be dictated to them though on the basis of an ethnic, social, or gender group. Ultimately it is about respect. Every writer deserves the freedom to explore what they need to, while being treated with the same artistic integrity afforded to those not side-lined by an ill-defined, and flawed labelling system. For a writer should, first and foremost, always be a writer.

About Reece Choules

Reece Choules is a regular contributor to both Litro and The Culture Trip. He lives and works in South London.

There are a lot of things that can you make you a writer and even more things that can make your writing works even better and super special. As for me, best custom writings online is that source and great way to understand meaning of special style, because I’ll always give an advice exactly about this place.