You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping I try to keep my books in good condition, but my copy of Lawrence Durrell’s Monsieur is looking worn now. I’ve had it a long time. I’ve had other books as long or longer, but Monsieur is battered, foxed, faded, broken – more decrepit than the chateau (depicted by David Gentleman) on the cover. I think that’s how it should be. It is a book about ruined lives, as so many fine novels are. It is also about the mystery of things. The world is not clean and bright. There are dark passages we must go down. There are doors we have never noticed until they open. Monsieur is set in the dust and shadows of somewhere we come across unexpectedly.

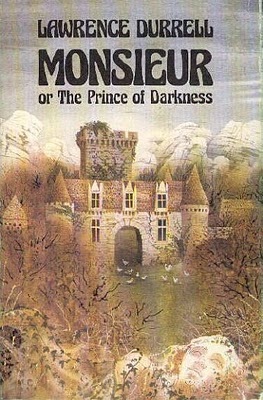

I try to keep my books in good condition, but my copy of Lawrence Durrell’s Monsieur is looking worn now. I’ve had it a long time. I’ve had other books as long or longer, but Monsieur is battered, foxed, faded, broken – more decrepit than the chateau (depicted by David Gentleman) on the cover. I think that’s how it should be. It is a book about ruined lives, as so many fine novels are. It is also about the mystery of things. The world is not clean and bright. There are dark passages we must go down. There are doors we have never noticed until they open. Monsieur is set in the dust and shadows of somewhere we come across unexpectedly.

Recently I came across a picturesque chateau. On our way to a famous ruin we saw a chateau not too far from Avignon. It was in the wine country, so the house was surrounded by vineyards. It wasn’t in a state of decay. But it was remote and unexpected and striking. I said at once it reminded me of Monsieur. Durrell lived close by. He may have known it. He must have known it. This was surely somewhere in his mind as he was writing the book. It didn’t resemble the cover illustration, however, which has more of a look of Avignon itself, the medieval walls and the papal palace perhaps as inspirations.

It was the setting of the chateau that was interesting. We find these places from time to time, often with ambivalent feelings. This was a sunlit July morning. The chateau, now converted into a hotel, had a benign look. There was neither mist nor moonlight. It was the remoteness that reminded me of Durrell’s book.

The complete title is Monsieur or the Prince of Darkness. I have heard it suggested that Monsieur is an old name for the devil. (“The prince of darkness is a gentleman.”) Did I wish to read a book with such a title? Yes. I thought it intriguing but safe, for this was Durrell, a serious and respected writer. I bought the paperback in Foyle’s, then walked down to the National Portrait Gallery. There was an exhibition of writers. An oldish man quite small in stature was signing the visitors’ book in front of me. I signed my own name beneath his. You can guess who he was, making a rare visit to Britain, appearing out of nowhere ahead of me. His book was in my hand. It felt like destiny.

Or perhaps it was temptation? I was not tempted by anything satanic. What intrigued was the culture of ancient Provence. I had heard the music of the troubadours. I knew something of the history of the region. Everyone knows of Moorish Spain, but the Moors had trading stations all along the coast of Southern France and beyond. The Moorish influence generated many things exotic to European eyes, including mystical cults at some distance from orthodoxy. Tolerance of faith and practice, embracing Islam and Judaism, ascetic orders and courtly love, made Provence a blend of cultures that produced a poetry and a music, as well as a way of life, that persist even in this century. Every St John’s Day (23 June) they dance the spiral dance, derived from the ancient Sufic rite, throughout Provence. We share bread and follow the Flame of Life through the city streets (after listening to boring speeches from civic dignitaries).

What has this to do with the book in question? Everything. The book moves from Provence to a voyage on the Nile to Venice. In Provence the mystery begins. In Egypt, far from the tourist haunts of Cairo and Alexandria, the English expatriates who people the novel are attracted to a Gnostic cult. In Venice, Sutcliffe wanders, as in Venice we do wander. He is not young, for this is a novel of maturity with faded lives leading towards death.

What first and indelibly impressed me when I read the Venetian section was Sutcliffe’s admiration for a young woman. I was her age then, not Sutcliffe’s. I appreciated the way desire was described. It was the way of a man experienced in these things. He was assured in a way impossible for the very young. I thought of Cyril Connolly’s similar encounter with a woman in Charing Cross Road. He recounts the true incident in The Unquiet Grave. He hadn’t the courage to speak to her, a stranger. Nor had I. But Sutcliffe, and Durrell himself it seemed, knew how to approach what they admired.

In Venice strange atmospheres are routine. Life becomes a masquerade, alluring and dangerous. It is not a city to take lightly. Nor is the Nile merely a river. It is a god commanding respect. Sailing the Nile, in the right frame of mind, is itself an initiation. The attraction of Gnostic mysteries, so prevalent in the New Age culture of our times, is a rebellion against the West’s materialism. The reality of here and now is but one reality among many. That is the feeling behind Monsieur. In life there is a darkness to be encountered. We cannot ignore it any more than we can ignore the immanence of death. We are encompassed by death. We are, as living beings, defined by our ephemeral nature. Monsieur begins with a death and the arrangements for a requiem.

Or, rather, it begins with a journey towards a requiem. The narrator takes the southbound train from Paris, a journey he had made “from time immemorial”. It was that phrase in the first sentence that made me want to read on. Sometimes it may seem that we have made such a journey, following in the path of previous family members, say. And there are the journeys we have made for ourselves over the years. But to speak of time immemorial is to place the event outside the course of ordinary living and into a metaphysical realm beyond time and space as we (imperfectly) understand them.

Were we to understand fully what this means then we would have a sense of Gnosis, of knowledge of the unknowable. This is what they seek in Monsieur, a means of comprehending unfathomable realities, like love and death.

Gnostic cults (of which there were many in medieval Provence) proved to be a dead end for me. They were not people asking questions of life, but, rather, they were offering all too easy answers in formulae that did not surrender to reasoned examination. I think one is supposed to surrender to the experience. That is a dangerous conceit, opening up oneself to all manner of manipulations. In reading we do not surrender: we engage our minds and our senses in ways that can enlarge our imaginative sympathies.

That is why I have not replaced my battered copy of Monsieur. It has a character, if not a spirit, that belongs to the book I found and took home and have not been parted from. The age-old Provencal culture, which retains its presence and its vitality, is something I owe to reading Lawrence Durrell. The book was the first of a series, but it remains the only one of the Avignon Quintet I have read. I don’t know if I ever shall read the others. There seems so much in the first. Re-reading it, I am drawn back emotionally and physically to a culture whose appeal is in its alternative to trivial materialism.

Durrell’s portrait of Avignon as shabby and backward I do not recognize. Perhaps in an earlier time it was as he says. But today it is a city of clean, light stone, of church squares with cafes and restaurants not always readily known to consumer tourists. Our favourite hotel is in a narrow street where no traffic goes. There are certainly no tour buses. Nobody wanders there. You have to know where to go to eat and sleep to fully experience Avignon. Other Provencal places have their own characters, which again are hidden away. Perhaps that is what is meant by surrendering to the experience.

Durrell’s exquisite prose, the English of someone whose soul rests elsewhere than lands where English is spoken, contains its mysteries. It is the prose of a poet invoking the elements of the scene. It invites enchantment.

About Geoffrey Heptonstall

Geoffrey Heptonstall is a poetry reviewer with The London Magazine. Recent creative work includes poetry for Dead Ink, The English Chicago Review, International Literary Quarterly, London Grip, Message in a Bottle, The Passionate Transitory, The Recusant and three anthologies, Connection, In on the Tide and Underground. There is recent fiction for Open Wide, Vintage Script and Writers’ Hub. New essays for Cerise Press and New Linear Perspectives are published this year. Geoffrey’s recent theatre writing includes a play, Providence, published in The Lampeter Review.