You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

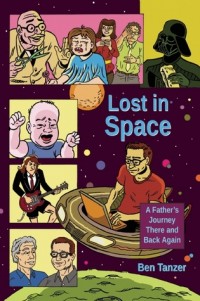

Go shoppingIn this extract from his forthcoming book Lost in Space: A Father’s Journey There and Back Again, Ben Tanzer takes one last adventure into the Italian unknown

Here’s what you need to know: my father is dead and Debbie and I are talking about having a baby. My father was a complicated mix of artist, teacher, activist, and world traveller, and yet despite that, he died with regrets about things he had, and had not, done. The regrets did not make the person, but coupled with his death their impact is profound for me.

We think we can escape our parents’ shadows, but moving away from them, or shutting off our feelings, even their death, does not make the shadows go away.

Children are different of course. The shadows come later, but even talking about having children makes the chance for adventure seem less likely, and Debbie and I have definitely not been on enough adventures together. And yes, I know, people go on adventures when they are parents, but will we? I don’t know, which makes me think even more about regret and shadows, which leaves me spinning.

It also makes me want to run away.

Not that I want to run away from the idea of parenthood or Debbie, but for at least one last time I want to think I can be someone who takes chances and can live in the moment.

Debbie is not interested in any of that.

“Go, go somewhere I have been,” Debbie says, supportive, though maybe hedging her bets a little, “but go, and then come back, cool?”

Cool.

To recap, my father is dead, we are going to have a baby, there are regrets and shadows, and I think we need an adventure, Debbie does not, and here we are.

Here being Milan.

I can head directly to Venice, which is technically my first stop, but the cheap tickets involved flying into Milan and I want to see it. I want to see everything. So I wander around, eat paninis, and stop at one church after the next. The light is brilliant, the women are beautiful, and there is a moment where I think, this is enough, I did it, I got away, I’ve had this experience, and I can go home now and become a parent.

But I press on. This is just the beginning.

I head to Venice, and I assume, incorrectly as it turns out, that the hotel will not be difficult to find since it advertises itself as centrally located to both the Rialto Bridge and St. Markʼs Square.

An hour later it is dark, I am chilled to the bone, and I am meandering through the twisty alleys and side streets of a city I don’t even vaguely know my way around and, wondering whether the hotel, or street it is supposed to be on, even exists.

During my search it strikes me just how alone I am on this trip. I have no one to express my fears to. There is no one on the streets to ask directions. And the one phone call I am able to make to what I think might be the hotel gets lost in translation as I have no idea what the person is saying and they clearly have no idea how desperate I am to find them.

Being alone is great when you want to write or dictate your own schedule. Being alone is just plain lonely when you’re lost.

Later, much later, and long after this trip, when at least one child is always in the apartment when I get home from work, I have to run with a baby jogger because there is rarely the opportunity to run by myself, and Debbie and I have to negotiate for free-time, I will better appreciate how great it was to briefly have thoughts and head space that were my own, as scared and lonely as those thoughts may have been. But that is still a long way off, and again, way after I turn down what I believe is the same alley I have walked down repeatedly and my hotel is sitting there, right where it should be.

Venice may be known for things like the Titians at the Accademia and the Pollock room at the Peggy Guggenheim, but it is the city itself that endlessly captivates. The streets twist and turn and constantly intersect. Where there are no streets, there are canals and bridges of all sizes. Water is everywhere, as are countless alleys, piazzas, and ancient buildings, many of the latter emerging from the canals like ancient concrete sea monsters.

Tradition holds that when you feed the pigeons in St. Markʼs Square, they will come to you in a swirling cacophony of wings, beaks, and shrieks. Which they do, though while it is fantastically entertaining, it is also much scarier than I anticipated. I may have intended to run from regret on this trip, but I hadn’t planned to be so scared while doing so.

I know this experience is a metaphor for the adventure to come, that parenting is going to be scary at every turn. Which I suppose may be obvious when written down like this, but it hadn’t occurred to me until I was so far from home, and so unable to do much about these feelings.

On the flip side, a subtle shift begins to happen in Venice as well. Maybe it’s the Pollocks or the pigeons, quite possibly it’s the gondola ride I take on the Grand Canal as darkness falls, something just completely overwhelming in its silence and beauty, but whatever experience it is, I realize that everything I see, I now also hope to one day see through the eyes of my still unborn child. A flip has been switched, and it’s not going to get un-switched, and so now I wonder how that child, or children, will experience the things I am seeing, whether they will like them or hate them, and how much I will become my dad, beseeching them to love something because it’s so amazing, yet flabbergasted that they can’t see it in the same way I do?

And speaking of which, I am soon seated at a restaurant in Florence and next to me, two men with wild hair and Oxford shirts are wildly gesticulating with their hands, their voices rising as they engage in a conversation so animated I wish I knew Italian.

I cannot follow what they are saying though, and so I decide to lose myself in an artichoke omelette instead. Moments later, fully lost in the omelette’s buttery wonder I fail to realize that one of the gentlemen has been trying to get my attention.

“Excuse me, American, no?” he says.

“Yes,” I reply wondering what local mores I have trampled on.

“What does this Castaway mean?” he asks.

This is not exactly what I am expecting, and I do my best to explain.

“It’s kind of like being thrown away by life,” I say.

He nods.

“So what did you think?” I ask.

The man pauses.

“A good movie, but not great cinema,” he finally says.

As he turns back to his friend, I don’t know what is harder to grasp, the irony of discussing a movie about a man adrift, or that I am discussing said movie with a man who reminds me so much of my father.

My father and I endlessly talked movies, but we will never do so again. He will never say to me for example, “How many masterpieces does someone need to make,” when I ask him what’s happened to Martin Scorsese’s ability to make good movies. Nor will he ever see Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, and how is that possible?

Fuck.

On the other hand, with children I at least have the chance to repeat this dynamic in some fashion. There’s no guarantee they will be interested in anything I want them to be interested in, but there’s a chance, and that’s more than I can say about my relationship with my father.

The next morning I am walking through the Accademia and moving along somewhat perfunctorily when I am stopped dead in my tracks. I am face to face with the David by Michelangelo, and I am spellbound, lost in its every curve and ripple. It’s so much bigger than I expected and so powerful looking. It practically glows.

I may be falling in love.

I move behind the David to see it from just one more angle, and when I do I find myself spellbound all over again. Hanging from the David’s hip is easily the longest cobweb I have ever seen in my life. It floats there ethereally, silent and beautiful, swaying to and fro, light and dust dancing around it like stars at dusk. Transfixed by the cobweb’s undulations, I am left with the following thoughts: first, how love can be so fickle and fleeting? And second, how can’t it be someone’s job to worry about such things?

A therapist once said to me that I was a good storyteller, but he didn’t mean it as a compliment. What he meant was that I told stories about how I wanted to see myself instead of exploring my actual feelings. Is this trip any different, and what about my experience of seeing the David? Was seeing that cobweb as profound as I imagine it to be, or do I need it to be, adding texture to a story that I have no choice but to write, because I have no choice but to write about it, if not during the trip exactly, then someday down the road?

I can already see where I am engaging in a certain amount of myth-making about this trip, describing in my notes the person I have convinced myself I am or wish I could be. But it is not the truth. I have constructed the world as I would like to see myself in it, cool, relaxed, and able to comfortably manage the idea that having a child is scary, or that my father can go and die, and at some reasonable point I can move on, because it’s time, and I have mourned enough.

I imagine that the falsity of all this will be as obvious to the reader as it now is to me, and even in my note taking, I force myself to dig deeper, searching for the places where the darkness and confusion reside. I only hope that I can continue to do so long after the trip.

I arrive in Rome during the early evening, a light rain dotting, then dripping down the lenses of my glasses, the sun just setting. The city seems so big and so empty and I am struck by how little I planned for all the loneliness and isolation that has accompanied my trip. This is, of course, what happens when you spend so little time by yourself. You don’t prepare for the fact that beyond the language barriers, you don’t realize just how much a constant lack of speaking and contact will begin to wear you down. Some of this is a lack of planning and vision about what I needed for the trip beyond the need for the trip, something I’ve never been good at anyway. When I want to do something I just do it, no research, no planning. I assume that I will somehow figure it out through sheer will and desire.

I won’t be able to do this as a parent though, an act that involves all the things I haven’t had to be, thoughtful about making plans, taking time to figure out how things work, and not only filtering the world through what someone else will need, but understanding those needs in the first place. I will have Debbie, and we will have each other, but what if we don’t know how to do these things and never quite figure it out? What then?

I don’t know. What I do know is that I cannot sit in my room and watch Turner and Hootch in Italian, and with that I head out in search of Trevi Fountain.

I walk along the deserted streets and I am stunned when I come upon the Via del Corso, a shopping area so teeming with people it feels more like a flash flood. I eagerly dive into the crowd before me, and I am buffeted by people from all sides, propelled forward by its force, and energized by the contact.

I eventually resurface to cut through an alley that I believe will lead me to Trevi Fountain. It is so dark, quiet, and not crowded, however, that I question whether the previous moments were real or just the longings of a lonely traveller.

But then there is light.

I turn a corner and before me is an explosion of bearded, muscle-bound statues astride waves of all sizes and surrounded by columns and sea monsters that spring forth from every possible direction. I have stumbled onto Trevi Fountain and it is larger than life.

I sit before it, and I try to take it all in, bathed in the streetlights and drizzle, and lost in its sheer audacity. It’s magical really, and as I sit there soaking it all up I am reminded once again of why we travel in the first place, to be lost in something so different than the life we know, as if we have entered another world completely. I feel as if I could leave Rome that night if I had to, satisfied and complete, but if I had I would have missed my night Piazza Navona.

I wasn’t even looking for it. I was just heading somewhere, and there it was, this sprawling piazza, full of cobblestones, balconies, churches, cafes, fountains, and people, people everywhere, leather-wearing and stroller-pushing, white-robed and black, vendor and caricaturist, homeless and lover.

I settle in at the Caffe Barocco, a slight chill permeating the night air as scruffy, corduroy-wearing troubadours belt out R.E.M. tunes only feet away. Unexpectedly, a handful of young American students jam into the table next to mine. They’re talking and smoking and talking and eating, and then talking to me.

“Do you want to join us?” they ask.

I am a little too excited to be hearing American voices, and yet there it is, a taste of home, all feelings of isolation gone, just like that.

They are full of questions and anxieties.

“Have you been traveling by yourself?”

“I have been traveling by myself,” I say.

“Where is Trevi Fountain?”

“Trevi Fountain is really easy to find,” I say, “I will tell you how to get there.”

“Is it hard to get around Rome?”

“Rome will feel small in a week,” I say, “and your time abroad is going to be wonderful, you will never forget any of it.”

As we talk I realize that as excited as I am to talk to them, I feel protective of them as well. They have been thrown into a new culture far from home, and it’s all so big, and I want to hug them so much, which is not a new feeling for me, this desire to protect people, and yet it’s different than how I normally experience it too.

One of the young woman looks like Natalie Portman, and while my first inclination is to check her out, it is quickly replaced by a completely different, and new, reaction for me, the idea that if Debbie and I ever have a daughter she could very well look like this, the dark hair, the big smile, the beautiful skin, and that someday she could be living abroad in some foreign city living a life I regret never having quite lived myself, but want for the children I have yet to have.

It is wonderful, and baffling, and I see now how some regrets and some shadows dissipate merely by bringing children into the world and watching them grow and thrive and live lives of their own.

I hold onto the young Americans as long as I can, but at some point we have to part. After that it is time to go home.

Ben Tanzer’s Lost in Space: A Father’s Journey There and Back Again will be published by Curbside Splendour Publishing on 18th March.

About Ben Tanzer

Ben Tanzer is the author of the books My Father’s House, You Can Make Him Like You, So Different Now, Orphans and Lost in Space, among others. Ben serves as Director of Publicity and Content Strategy at Curbside Splendor and can be found online at This Blog Will Change Your Life, the center of his growing lifestyle empire. He lives in Chicago with his wife and two sons.