You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

It’s nothing like the casinos back home, I made sure of that. There was a lot of resistance. The whole point of the casino, they said, was to remind people of home, where there are two certainties in life: casinos and airports. But no, I said. Here, there are no certainties at all. And we can make them forget that home was ever anywhere but here.

We’re packed tonight. It’s going to be an eclipse, and a big one. As the earth and the moon cross paths, we’ll be able to see our shadow. With our domed glass roof, everyone will be able to watch without stepping away from their bets. And we’re serving the best baked potatoes known to humankind. We’ll all be crunching down on perfectly crisped potatoes as we eclipse the big crispy potato in the sky.

They told me to make sure this one was big. After all, the timing is convenient, what with the situation in Paraguay. “No Paraguay,” they all said on the call, “Just fun. Make people forget.” The investors think tonight could be decisive. The event of the century, a falling wall or a burning man or a stocking wood, just the thing to catapult our casino from curio to cultural institution. I’m not so sure, but I intend to have fun either way.

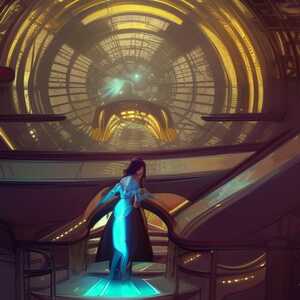

From my vantage point by the concierge desk at the top of the building, I can look down to the main floor, and it certainly looks like fun. I can see some of the bigger games of the night. None of the card games from back home; no roulette. The clientele here would have tired of that within days. Instead, they bet on each other. Anyone can place a bet on anything, all blockchain enabled.

There are some patrons rock-climbing up an enormous rock-face carved out of the ground itself in a corner of the dome, and the bet seems to be who can stay up the wall the longest. A few circles of people holding up various numbers of fingers, mid-never-have-I-ever, as usual (social-media-supported for fraud prevention). And a lot of the dancing seems also to be of a competitive nature. With the exception, as ever, of Pamuya. She’s here every night, and she never bets on a thing. Since she arrived a few weeks ago, she just dances, talks, revels in the atmosphere. My management team spotted her in the very early days and asked me if I wanted her removed for non-participation. Once I told them who she was – one of the Paraguay Eight – they agreed it would be best to leave her alone. In truth, no one in here recognised her. Even if they kept up with the news, the harried and hollowed-out political prisoner from the pictures bore no resemblance at all to the joyful, healthy woman in our midst. Although she didn’t play our games – or rather, because she didn’t – she was a secret beacon, a momentary reprieve for anyone who needed one. So I let her stay.

The theme tonight is Good Sports. We always have themes. Too many people in the casinos back home walk around in cargo shorts and thongs. There’s a dress code here, even on the main floor, and it changes every night, and if you didn’t get the memo, then we can tell you weren’t meant to be here, and so you aren’t here. Tonight, in our sportswear. I’m dressed as a ballerina. They’re athletes too. My powder-blue tutu contains 100 yards of imported tulle, and the bodice is covered in Swarovski crystals. Our patrons have largely gone for more conventional options – cricketers in baggy greens and esports people in their sleek black tracksuits and netballers with their pleated skirts of navy and yellow and white, which occasionally flounce open at the split and give a glimpse of pale upper thigh. You have to be pretty fit to live in a place like this. So our crowd are certainly something to look at. And yet these bodies feel uncanny, dressed up for sports. It’s a different kind of fitness. These are functional bodies. Fit from necessity, but with a different purpose; survival, and a little vanity, but no excellence. And, despite all the UV protections available, still with such heavy tans. Thick-skinned, we are.

My eye drifts back down to Pamuya. In the flickering light of the fire-lit dancefloor, her masses of tightly curled black hair dance a half-beat behind the rest of her. She seems to always have a glow around her – this is what I think when I’m in a romantic mood. The more pragmatic explanation is that she’s the only pale person you ever see without a tan, so her skin is just more reflective than other skin. She’s wearing a kilt. I’ll have to ask her why. One more question to hold her attention.

An alarm goes off on my phone and I hurry to the kitchen to check in on these potatoes. Need to make sure they’re on schedule to be ready for the eclipse. I even hear some snatches of chatter about the potatoes on my way. The smell is leaking out of the kitchen and into people’s chit chat. “–slow roasted–” I overhear people say as I swish past, “–four hours–”, “–ones with the red skins–” and “–sides of horseradish–”, I hear. That last bit is wrong. I hope the rumours aren’t outstripping what we can deliver. I open the swing doors to the kitchen but quickly notice the tutu won’t let me move much further through the cramped mass of sous-chefs and kitchen-hands.

“How long?” I holler.

“Thirty,” my head chef calls back, pulling a large tray out of the oven and flipping them with her bare hands. She slams the tray back into the oven and licks the hot grease from her fingers. I check my astronomy app against the evening’s runsheet. The height of the eclipse is in about an hour – plenty of time to get these roasted beauties out among the crowd.

“Thirty,” I respond. “Not twenty-nine, not thirty-one.”

Descending these stairs to the main hall, I feel like Eliza Doolittle every time. My tulle and I cascade down the steps, a natural phenomenon, and the room is dotted with Colonel Pickerings, agape at the sight of my splendour. I’m part of the experience, of course, something you can bet on. The smiles on some of the patrons’ faces will be owing to the fact that they’ve just won big on predicting the colour of my outfit or the exact minute when I will descend to the main floor. But there surely are some who revere me without any kind of agenda. Pamuya doesn’t seem to be one of these – she’s stepped off the dance floor for a while and is surrounded by smiling faces of her own. She seems to be telling some kind of story, her skinny limbs juddering through the air with an awkward grace. I orient myself to her, but get pulled into a nearby conversation before taking a single step.

“Albeda,” says someone dressed as a wrestler. I recognise him as one of the American officials stood down from the Paraguay negotiations. I wasn’t expecting him here tonight. My eyes flick nervously to Pamuya, but I go to him, eager to keep her off his radar.

“What’s your pleasure today, sports fans?” I ask.

“We’re taking bets on the way this whole Paraguay situation wraps up,” he says.

“Are you sure it’s not Uruguay?” asks one of his friends, one of our investors, wearing only a speedo.

“Oh, shut up,” the wrestler replies, a laugh belying his mirth at how casually he and his companions can turn geopolitics to sport.

“Brandon here thinks the US will launch the missiles overnight.”

“Sounds stressful,” I drawl, expertly smoothing the surface of this ugly exchange. “Why fill your mind with all that when we’ve got a beautiful eclipse to watch?”

“A what?” asks the one in the purple baseball uniform who might be Brandon.

“The eclipse tonight,” I clarify. But Brandon – actually, everyone except Speedo – blinks back at me blankly. Speedo, one of the investors who believed tonight would achieve “event of the century” status, is staring daggers at me. “Just you wait,” I continue, preparing to take my leave, “it’ll be a treat. And so will the potatoes!”

Uncanny eye-rolls from two synchronised swimmers in the group.

“Great,” says one.

“More potatoes,” says the other.

I smile and excuse myself, casting an eye about the room to ensure I haven’t missed any other loose-cannon political rejects on the guest list.

We’re all growing weary of potatoes by now, that’s not a surprise. But they haven’t tasted these potatoes. These aren’t just any potatoes. The eclipse, on the other hand – I’m surprised they didn’t know about that. At that moment, one of the rock-climbers loses their grip for a second, crying out. My eyes flick up to them. Seeing that they’ve recovered, my gaze wanders up further, up to the dome, where I see that the eclipse has actually already begun. You have to look closely to see it, but it’s there – the little shadow of us on the bottom-left of that bright disk in the sky. “Look!” I cry out. A few people nearby turn my way. “The eclipse! Look, that’s us!” Now everyone around me is looking up through the domed roof at the sky.

“Where?” asks someone in ski gear.

“So it is,” says a nearby pole-vaulter, and they hoist their pole up towards the glass dome to point to our shadow.

“We’re right over South Africa,” says someone else – I don’t see who, my eyes are back on the sky. And then no one says anything else.

Our shadow is so small. At this early stage of the eclipse, you could miss it. The earth is particularly bright tonight, with Antarctica shining right at us. Much brighter than we look from down there. We could turn out the lights and douse the fires in this dome and we could still see everything by the light of that place that made us. It might be my job to make people forget, but the truth is, we all have memories of that place. Most nights, the earth is just like a moon, it waxes and wanes and gives us more or less light. But in this moment, looking up at that bright, doomed disc, all our ridicule and our bets about it bounce back and hit us with a painful glare.

Noticing a bit of hubbub, I look around, and somehow, no one’s looking at the earth anymore. Most people are already going back to their conversations, their bets, their turn to climb the walls or out-dance each other or seduce each other, for the chance to walk away at the end of the night with a few extra dollars in their accounts. Only one face is still turned skyward. I finally make my way over to Pamuya, who has sat herself down on a log in the forested corner of the room. The perfect vantage point, where you can peer up at the eclipse through the branches of plane trees. And yet this picturesque spot is curiously abandoned. I plop down beside her, knowing the rough bark of the log will tangle and tear my tulle, but somehow past caring. She doesn’t take her eyes off the sky, and so I join her, looking up at our tiny little shadow as it creeps across the world.

“What’s with the kilt?”

“There’s that log-tossing sport from Scotland.”

I nod, pretending to know what she means.

We sit like that for a while, both staring up through the domed glass roof. I take my eyes off the sky every now and again to look around. People are noticeably less energetic than before, or more. Listless, clawing around inside themselves for the easeful party spirits that had been there moments before, before they were reminded of home. Or maybe they’re just tired. It is late. Speedo has gathered up a few of the other investors, and their eyes are swinging around the room. They’ll catch me eventually. For now, I’m grateful for the cover of the trees.

“Our shadow will draw this line across the earth,” Pamuya says, “probably a bit like this:” and her arm describes an S curve that flicks up at the end. “It’s called the line of totality.”

Her hand comes to rest next to mine, exerting too much gravity for such a delicate thing.

“Have you tried the potatoes?” I ask her. I can see one or two people relishing them, but largely they’re going half-eaten on plates dotted around the room. We all thought some of the other crops might have taken off by now, but maybe the potatoes are the only thing that will grow here. Pamuya looks away from the sky for a moment, and her pale, narrow eyes shine into mine. There’s a beaming smile on her thin lips.

“I love potatoes,” she says.

“Even now?” I ask.

“I could eat them forever,” she says.

“Well, you’ll have to try the ones we have tonight,” I say. She’s already looking back at the sky, so I look back too. “Roasted for four hours in three different types of fats,” I say. She makes a noise I like. “I’ll grab you some when they come around.”

“Thanks,” she says. And then, after a moment, “They remind me of home.”

And then we lapse into silence. There’s a part of me that’s itching to ask her. About Paraguay. About everything that’s coming to a head. About home, and what it feels to be exiled among people who chose to leave. I can barely bring myself to tell the investors that I want a weekend, so I can’t imagine what it took for her to say what she said in front of her whole country. Another part of me wants to get up and leave her, to prostrate myself at the feet of the investors, to do whatever they think will work to make tonight a success. To make sure the potatoes are reaching every corner of the room, and the people are betting big, and the house is winning, and the drink is flowing. But being by her side, looking up at the earth, it’s like losing reception on myself. Only the faintest signal can get through this calm. I imagine myself into the line of totality; some place back on earth cast into total shadow by the moon. The mid-morning darkens. Do the street lights come on? Has it been planned for?

Perhaps not. Perhaps even now, nocturnal animals and secrets are awakening too early, darkness glaring in beady eyes like morning sun. Dictators and cheats aglow with possibility in the line of totality. But the line must have blurred edges. There must be places where our shadow, so total in the next town over, registers little more than a passing cloud. Smears of partiality either side of the line of totality. Fingers hovering over buttons, resolve dissolving with every passing second. Yearning half-strangers sitting side by side without the courage of total darkness in which they could reach out; in which my hand could be pulled into the gravity of hers. The line of totality. How many people will be in its shadow? Consumed by us as we float overhead.

About Georgia Symons

Georgia Symons is a writer of prose, theatre and video games. She lives in Narrm (Melbourne), Australia. Her recent video game Wayward Strand is available on most platforms.